.jpg)

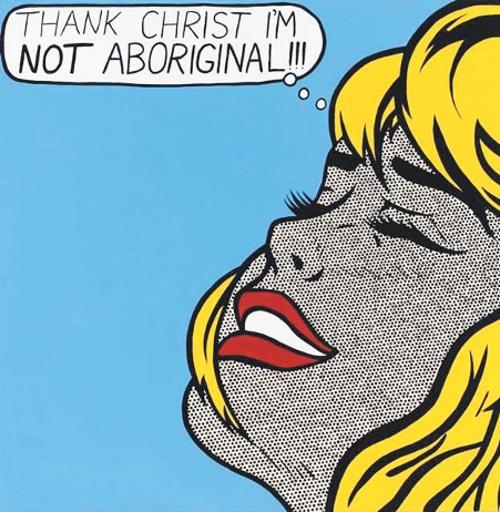

It was the photomedia artist Destiny Deacon who first used the term 'blak' in the Australian context. Deacon, who wavers between describing herself as a political artist and 'a bum photographer', says the term takes the 'c' out of ‘bloody black cunts’, a racist jibe she has endured throughout her life and in particular during her childhood in the inner Melbourne suburb of Brunswick. On the other hand, Deacon’s contemporary Fiona Foley believes the term 'blak' is empty and meaningless. The title of this edition 'Blak on blak' invokes the idea that we as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are now in an intellectual position to self-reflect and to fearlessly criticise our practising artists in a straightforward, public way.

Whatever position you take, the term 'blak' which Deacon devised in defiance of the inexorable power of the English language, expresses our right to state who and what we are, to self-identify; not as Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander or Indigenous although we are some or all of those things. Collectively the artists in this issue refute the ideas that cluster around the term ‘Aboriginal’. Creatively, artists such as Deacon and Foley challenge the norm of what it is to be Aboriginal.

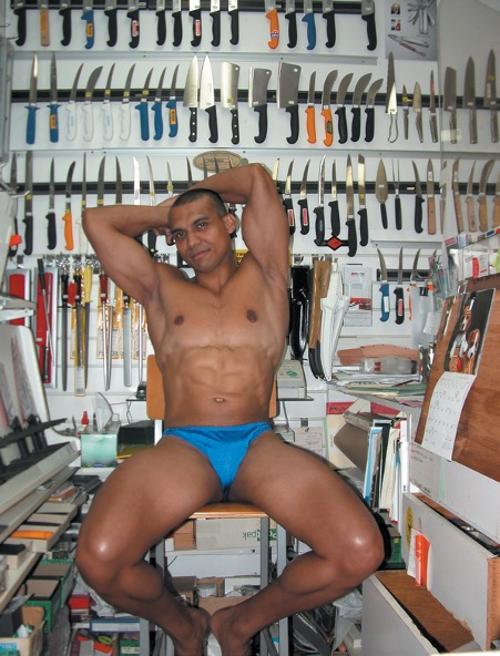

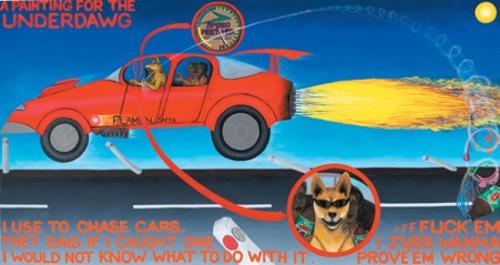

Richard Bell is a spokesman - for himself and for many others. He is unafraid of the consequences of telling it like it is, and in this he fights for us in the wars of representation. His radical political persona sometimes even threatens to eclipse his work; his t-shirts (‘White girls can’t hump’) draw him into the performance of a public identity, a bombastic cultural warrior. He spurs on the younger generation of artists, and not just those from within the proppaNOW collective. Make no mistake, politics drives the work of these artists. Their art is unapologetically a form of political activism.

As a community, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are trying to repair the psychological damage done to our collective identity in the culture wars of the Howard era. As his regime teetered on the edge of a bitter electoral defeat, the former Prime Minister set out a new policy on Indigenous affairs, its key plank a referendum on how the Constitution might be altered to reflect the special status of Indigenous people. He also declared that the ‘challenges’ he felt around Indigenous identity politics were an ‘artefact’ of his childhood, mired deep in the suburbs of Sydney in the 1950s. Almost in the same political breath, he articulated the need for a summary approach to bring remote Aboriginal communities across the Northern Territory under the paternalistic control of the Commonwealth, compulsorily acquiring Aboriginal land and banning the consumption of alcohol and pornography. The great shame of the Intervention was that it was politically unopposed.

'Blak on blak' is perhaps the first attempt to draw out how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander arts writers and curators think about our practising artists. We are compatriots, but there is a place for us to criticise their work as fellow countrymen and women. As Vernon Ah Kee puts it, we see things differently. The work inheres certain ideas about Aboriginality in the urban context and ultimately we share in the intellectual and aesthetic meaning of their work, its effect. I often complain about the dearth of true, intellectually honest criticism of Aboriginal art. Let’s hope that 'Blak on blak' might be a starting point, to develop a critical culture within Indigenous arts writing; one that acknowledges our common identity and which explodes the myth that we are uncritical.

My guest editorship of Blak on blak would not have been possible without the kind assistance of the Copyright Agency Limited (CAL), my assistant guest editor Tess Allas, the Queensland Indigenous Arts Marketing and Export Agency (QIAMEA) and of course Artlink’s executive editor Stephanie Britton and manager Mairead Doyle. I’d also like to personally acknowledge the artists - Vernon Ah Kee, Tony Albert, Richard Bell, Bindi Cole, Fiona Foley, Jenny Fraser, Julie Gough, Gordon Hookey, Dianne Jones, Gary Lee, Beaver Lennon, Yhonnie Scarce and the estate of the late Lin Onus, and their representing galleries.