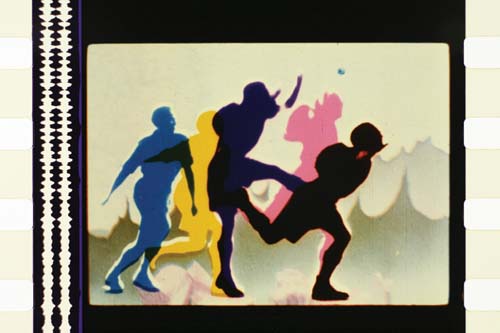

Len Lye (1901-1980) - artist, traveller, poet, technician, thinker - was a happy chap. Happiness was his philosophy – 'individuality, happiness and the present moment' as an early unpublished manifesto put it – and it poured out of his work in all media: film, kinetic sculpture, sound, animation, painting, doodling. Even more remarkably, Lye devoted himself to the encoding, the triggering of this emotion: like Sergei Eisenstein (a charming photo shows the artist as a student in Eisenstein’s masterclass), Lye was an ‘engineer of sensations’, someone who believed that the dynamic qualities of any artform could help create exquisite happiness and heightened awareness in its receivers ... and all without the aid of any chemical stimulants.

But such unadulterated, uninterrupted joy is surprisingly difficult for today’s art patrons (at least, those of adult age) to take: confronted with the exuberant, radical infantilism evident in the generous Lye survey show at ACMI, you can see them scratching their heads, wondering: where is the dark side to this guy? The Gothic touch? The guilty Freudian secret? The obscure, hidden meanings? What you see is what you get in Lye: it’s all on the surface, traced in lines and colours, cuts and sounds. To be forewarned is (hopefully) to be disarmed.

If there is any secret to Lye, it is in the grand connective plan he always aspired to: all arts, all scientific knowledges, merging into a kind of ecstatic materialism of creative, blissful enlightenment. In 2009 are we collectively closer to, or further away from, Lye’s dream than when he departed our mortal shores 29 years ago?

Anyone drawn to the irrepressible figure of Lye – and locals should know that in France, in Portugal, in many places, he is considered the greatest artist from the New Zealand-Australia axis to emerge during the twentieth century – will savour this show. It offers up an extraordinary archive of documentation, much of it collected by the man himself. There are rarities on display, such as his paintings and drawings of sea life. But I wonder: for the spectator new to Lye, does this show provide the best introduction, the best 'immersion'?

Lye dreamed big. Monumentality was part of his art, his vision. The part of the exhibition devoted to his kinetic sculpture is the most dramatic – that is, if you happen to be standing around or passing through when the objects are actually in motion (and loudly so) – but there is a sad corner where the wall display informs us of his wish for large scale versions of several works, and a rather tiny video monitor showing us the ephemeral fruits (so far) of this campaign since his death.

This exhibition (even though it is extensive) lacks the sense of scale that Lye might have liked. I kept wishing that the films, paintings and drawings could be projected over the vast, black ACMI walls, rather than being sequestered in intimate viewing booths or arranged forensically in glass cabinets. As the effusions of a true Twentieth Century Man, Lye’s oeuvre throws down the gauntlet to gallery exhibitors: what’s more important, finally, the ‘real thing’ beautifully preserved (and thank god – or rather, thank the Len Lye Foundation - for that), or dramatised, extended in all its technical reproducibility?

A strange reversal has been steadily happening in cinema-themed exhibitions over the past decade, both here and abroad. The touring Stanley Kubrick extravaganza, shown by ACMI, captured this moment in all its bureaucratic oddness: suddenly (as a friend melancholically commented), it was more important to see (through theft-proof glass) the real, crummy, fake old space suit that some actor wore on set in 1967, than it was to experience the metamorphosis of this humble prop into dazzling, gleaming cinema ('2001: A Space Odyssey') on a big screen. So the reversal is, often quite literally, this: the films (why we are there in the first place) get smaller in projection size, while the attraction of the behind-the-scenes ephemera is magnified.

The same trend has been evident in the Cinémathèque Française shows devoted to Pedro Almodóvar or Jacques Tati: the emphasis is on the minutiae of props, script notes, technical trinkets, design sketches, book covers, letters or postcards from famous friends, and the like. There is a simple, obvious explanation for this bias: most such shows are based upon, and happen due to the benevolence of, special archives devoted solely to collecting every trace of an artist’s life and career. (And – side note - to think of the astronomical number of great filmmakers, long dead, who have yet to receive such archival attention is truly frightening.)

It is all, in itself, fascinating stuff. But is a gallery space – and a ‘blockbuster’ show (all sense of proportions kept, because Len Lye at ACMI is not exactly 'Salvador Dalí' at NGV International) – the best place see it, study it, appreciate it? A forlorn little ‘reading room’ – a shelf of facsimiles of Lye documents and publications, which no visitor spent more than one minute flipping through in the hours I was there – points to the ill fit between the ideal functions of Archive and Gallery.

This is the kind of exhibition you immediately want to re-arrange (re-curate) in your head, if not (alas) on the spot. The show is genre and medium bound: paintings here, sculptures there, film animations here, how-to tools over there. It’s too neat, too categorical – especially given that the great constant of Lye’s career was his ability to keep exploring the same key obsessions through every medium he touched. I love the doodles, for example: Lye fastidiously kept every darn doodle he distractedly made even while talking on the telephone, because he believed the results aided in discovering forms and processes needed to bypass the conscious, rational, conventional mind. OK, then: I would start with a doodle, and try to take it for a walk through the gallery space, turn it into a wave, tracing a transversal line through film, painting, and the rest: since ‘perpetual motion’ is the subtitle of the show, the spectator must have a living, visceral sense of how every work transforms itself into every other work, backwards and forwards, during Lye’s ceaselessly productive life.

Now, we can only imagine how Lye himself would have scattered the cards of his Collected Works in such a grand space as this – that is, if he could ever have stopped creating new works.