Martha Stewart would gasp; Nigella's bosom heave; the Backyard Blitz team leap into action with hi-gloss and potted colour. 'The Christmas Tree Bucket: Trent Parke's Family Album' is a timely antidote to ideals of Christmas present. Not in Parke's family's home the life-styling pervading magazines and television, but less polished enactments of the season's traditions: presents loaded in a laundry basket (that's blue plastic, not wicker); decapitated, dancing and Piñata Santas; a desperate retch into the Christmas tree bucket.

Parke is renowned as the first Australian full member of Magnum Photo Agency. This exhibition shows his latest body of work comprising 68 images that can be broadly divided into two categories, those documenting Parke's family's Christmas and snaps of other family moments. The titling is clever: it finds a way to blend the two which, the artist's statement makes clear, is intended. Entering the exhibition, the viewer meets curtains of golden Christmas wrapping paper parted to frame 'Christmas Tree' (2008) a macabre shot of a skeletal Christmas tree, encircled by a bank of its dropped needles. Within the gallery, there are wall text extracts from 'Twas the night before Christmas' and 'Silent Night' and the actual tree, still surrounded by its needles, wrapped as if it is a fragile and valuable object, the few needles clinging to its crown encased in bubblewrap.

This Christmas styling camply amps the ominous undertones to Parke's family Christmas; priming the viewer for the artist's darkly observed images. It is also the factor that pushes the non-Christmas images to a secondary place, despite the amusing nexus between the text 'nothing was stirring, not even a mouse' and 'Rat and Cheese' (2006), in which a dead rat lies under the stairs.

Key to this sinister Christmas is the figure of Parke's nappy-wearing son Dash. In 'Christmas Eve' (2007) the viewer is distracted from the large Christmas tree gracing the living room by the tiny blonde child sitting in the hallway. Here Dash possesses the preternatural omniscience and worldly-wise visage of a medieval Christ-child, his dignity undiminished by the conical party hat affixed to his head that lends him a Chucky-like evil. Elsewhere, Dash nonchalantly dangles a Santa's head. In 'Dash and Doll' (2008) the dear wee man, clad in a white jumpsuit and fairy wings, lies full-length on top of a doll, to plant a kiss on her nose. This tender and innocent moment with its ridiculous yet indubitable sexual connotations is not hard to read as a comic contribution to the Henson debate, even though Parke's images are not set-ups but photos of actual events: spontaneous moments put on 'pause' and preserved.

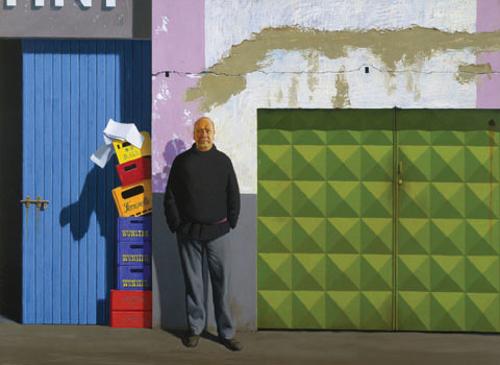

The small sharp Erwin Olaf exhibition 'Selected Works', also at ACP, provides a telling contrast. Where Parke is humorous and affectionate, Olaf's elaborate and meticulous constructions showing, as the room-notes say, 'evocations of human isolation', are mean. And where there is a lot of currency in contemporary culture for laughing at nostalgic suburbia, this is contemporary suburbia presented with faithful if wide-eyed affection. Some of the strongest images are snapped from family life: the hysterical burning house themed birthday cake in 'Fireman Uncle Heath's 37th Birthday Cake' (2008); the odd image 'Grandpa's Chair' (2006) of grandfather nursing grandson, taken at an angle so that the baby's bald head obscures the older man's face and tops his knees; the rib-like grease traces of sausages on a baking paper-protected barbeque, reminiscent of dried blood-stains on a shroud in 'Bar-b-que' (2008).

Less successful are those works that are less surreal or hyper-real in presentation. Some of the quieter, banal moments feel exactly that, like fillers. There could have been two tight shows here, presented at different times or as interrelated exhibitions. Parke's decision to present these works as one body is consistent with his previous series, which follow through particular themes at length and with the distinct differences between his practice and those of Darren Sylvester, David Rosetzky, Tracey Moffat and Erwin Olaf, who produce slick exhibitions that variously emphasise character, narrative and disaffection. Where some images could have been omitted without loss, it is the otherwise successful festive wrapping of the exhibition that forces the non-Christmas-themed images to the outer.