At a time when the prickly hackles of gender inequality are raising their ugly hides once again, an exhibition at the Carlton Hotel in Melbourne addressed both the lack, and the plentiful bounty of artwork made by women in Australia. 'Girls, Girls, Girls' presented work by 36 artists and collectives linked by no other unifying context than their gender.

At first glance an exhibition connecting work made by people of either the same gender, race or social status can seem a little tokenistic. However despite what many may believe, current statistics published on the anonymously authored Countess blog (http://www.countesses.blogspot.com/) point out that in Australia's major contemporary art spaces and art journals, feminism may just as well have never happened.

According to Countess' statistics all but one of Australia's key arts institutions maintained a higher percentage of men exhibiting than women. The worst offender being CACSA (Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia) with 77% male and only 23% female artists exhibiting, whereas the most equal distribution was seen at 24HR Art in Darwin, who were actually the only institution to show more women than men, with most of the others spreading within the bell curve of 65% - 35%.

This tallying and graphing tactic is old hat within the paradigm of first and second wave feminism and has accordingly slipped from favour in recent years. However as was identified at a forum organised last year by Gertrude Contemporary Art Spaces, Melbourne (60% men: 40% women) entitled 'Feminism Never Happened', many things have slipped from the feminist vocabulary that perhaps are still crying out for resolution and discussion (some examples that come to mind are: equal pay, flexible childcare arrangements and the objectification of female sexuality).

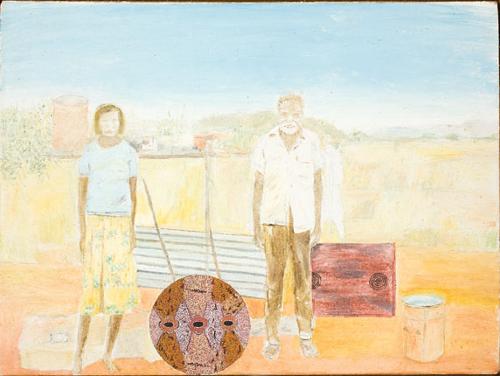

'Girls Girls Girls' seems to enter this problematic terrain with an encouraging irreverence. With the simple act of mustering women of no particular relation together in one rambling, mad exhibition that stretched throughout the many rooms and corridors of the Carlton Hotel's gallery spaces, a conversation formed that was organic and, to an extent, spontaneous. Presented with very little didactic or curatorial intervention (wall labels were more like casual annotations, written in pencil on the walls, or scrawled in biro on post-it notes), this exhibition was akin to listening in on the artists as they ventured their own voices into a discussion that is usually dampened with a cool ambivalence.

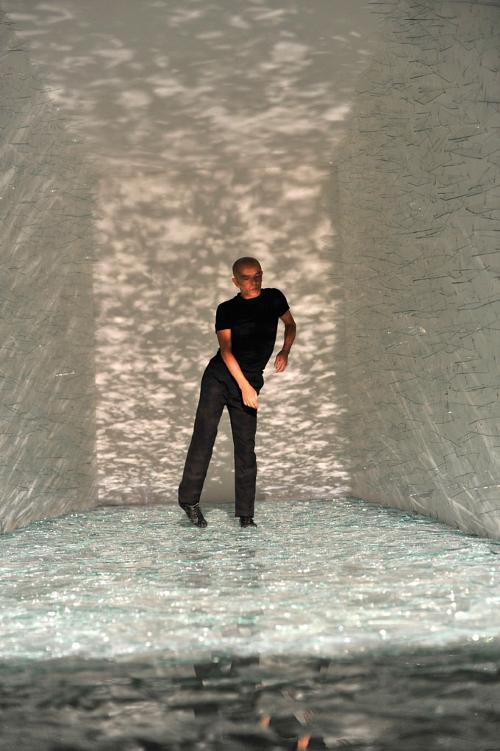

On first glance I was dismayed by what appeared to be a simple reiteration of the same old stereotypical feminine tropes of sex, gender and domesticity. But upon my second visit, a strange turning occurred. As I watched the Kingpins run amok in what appeared to be a prim English village in their video work 'Hieronymus Posh', the theme song to the musical 'Annie' sung by pre-adolescent girls (clips found on YouTube and compellingly compiled by Elvis Richardson) sifted in from another room. The mantra of 'Tomorrow, Tomorrow' began to gain a new currency in this context as a jaded revelation of our pioneering femo-sisters' failure to achieve their aspirations. (Not to mention the fact that this bizarre Freudian tale of an orphan girl saved by a super-rich Daddy was the catchcry of a generation of young girls who are today's third-wave feminists). Adding to this was the frustration inherent in Virginia Fraser's maddeningly robotic hula-dancing polar bear in her work 'Blue Room', whose eternal gyrations were coolly lit with fluorescent junkie lights and spoke of a kind of sexualised automatism that is all over women in contemporary culture. All of this coagulated in the hot-red and pink anger of Kate Smith's ironic-abstraction paintings, and the hateful luridity of Narelle Desmond's large red beanbag emblazoned with the word 'SLUT', which together struck me as pleasingly aggressive.

Anger has always been incredibly important as a feminist tool. As an emotion that for generations women were not entitled to express, anger has come to signify the progressive dismantling of patriarchal social structures. However, the twist with this exhibition was that these artists, who are sadly too numerous to discuss in detail, were able to skew the 'reclaim the night' simplicity of the 'all girls show' strategy. 'Girls, Girls, Girls' was imbued with such a delightfully angry irreverence that the usual criticisms of a show that foregrounds gender became difficult to uphold. It didn't care what you thought. It just wanted to talk, and it wanted to talk in whatever accent it felt like. Rather than the carefully considered academism that some exhibitions about feminism attempt, 'Girls, Girls, Girls' was more like an old-fashioned mustering. A reining-up of wild fillies that could possibly encourage mobility forward, beyond and outward, with the herd urged on by the shagirl slogan in Starlie Geikie's work: 'Brave the abyss, child of the wild wind'. And indeed they did.