Slotted neatly into the side of a hill and surrounded by vineyards and breathtaking views, the impressive TarraWarra Museum of Art's clean sophistication struck up a curious conversation with Kate Rohde's latest work, flourish, created especially for the North Gallery.

On entering the museum I walked through the main exhibition space towards what appeared to be a shrunken palm tree, slightly bent. An undersized and suspiciously glossy bench placed nearby looked too flimsy to sit on. Palm and bench were framed by a large window whose glass met the floor and faced neat rows of grapevines, dropping the last of their leaves while pinned to rolling gum-treed hills. The juxtaposition of these two elements brought to my mind a new housing estate I passed en route to Victoria's Mornington Peninsula one winter day. I drove under big grey skies, past gums, sodden paddocks, wind-swept water views and, suddenly, saw palm trees, looking as stunted and out of place as this one.

Rohde flanked her lone palm to the right and to the left with roughly rendered green walls that ran the length of the gallery. Nestled into the walls were several alcoves inhabited by papier-mâché animals, beige in color and textured to resemble weathered stone. There were hares and also squirrels which, by virtue of an antipodean sensibility, perhaps amplified by my rural context, I first mistook for brush-tailed possums.

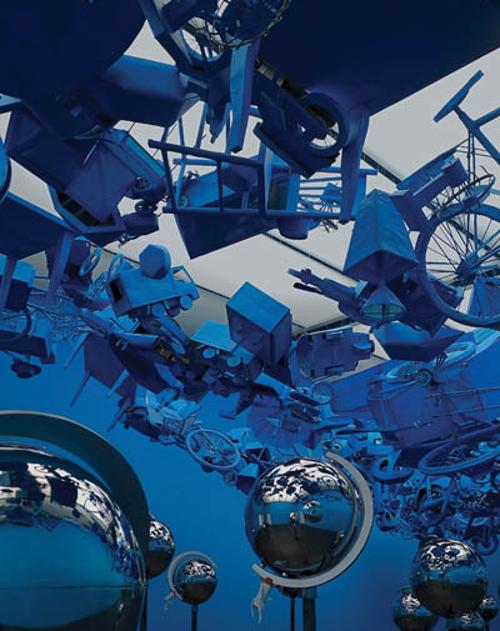

Rohde is not interested in an Australian landscape. Behind the vivid green walls she created four European 'gardens' each devoted to one of the four seasons: Summer, Autumn, Winter and Spring, no doubt inspired by time spent in the manicured grounds of the Chateau de Versailles during her recent Australia Council residency in Paris. Each enclosed section contained an ornately decorated vitrine, themed according to the season represented. Winter was frosted, encrusted with ice crystals and topped with misshapen, lumpy ice owls. Enclosed behind perspex a larger white furry owl spread its wings over ermines and rabbits, whose winter coats were encrusted with brandy-coloured jewels. Spring emerged all baby pinks and blues, sparkles, magic crystals, paper flowers and fur, evoking many a young girl's fairyland fantasy. Blue weasel-like creatures with sharp teeth and red glitter mouths posed around a Copernican horn of plenty, from which toxic-looking grapes tumbled.

A lurid pineapple topped piles of orange and yellow resin fruit arranged on Summer's sticky looking vitrine which housed a pair of fluffy yellow parrots with beaded faces. A paper garden, big-leaved and brightly flowered, had taken root and spread itself in the space with tropical vigor. Autumn's enclosure rested above brown paper creepers and few coloured leaves had fallen on the floor. Inside, rats, mice and birds of prey were arranged on a broken boat wrecked in a sea of hair, an arrangement apparently derived from a headdress once worn by the French queen of excess Marie-Antoinette.

While Rohde's vitrines were instantly seductive, enticing you to come nearer with glitter and detail, their sparkle faded quickly. Seemingly intricate ornamentation created out of resin, seen close up, resembled patterns squeezed out of cake-decorating tubes. Coloured craft-paper leaves were strung together like home-made Christmas decorations, and large scrunched balls of white paper pretended to be mounds of snow. Underlying supports were so roughly rendered that the MDF beneath was clearly visible under expanda-foamed features. Rohde's fluffy birds and bejewelled animals looked like puppet fill-ins in a Muppet Show period piece. There is a sense of the works having been created in a frenzy of building, joining, gluing, folding, squeezing, molding, coating, wrapping; the intricate detail and craftsmanship of antique objects has been replaced with contemporary slapped-together excess.

In Rohde's installation the artistic sensibilities and excesses of the seventeenth and eighteenth century European upper class collide with the flimsy aesthetic of twenty-first century sweat shop merchandise found in a suburban two dollar shop. Rohde holds a plastic mirror to objects from the past, wipes away the patina of refined luxury and juxtaposes the excesses of then and now, thus exposing the ridiculousness of both.