I am a good boy is a young woman's exploration of concepts of masculinity, the decline of male identity and the current crisis of manhood. The artists, Mitch Cairns, Marley Dawson, Christopher Hanrahan, Todd McMillan, Ben Quilty and Pete Volich are young males who do not necessarily see the interrogation of male identity as key elements of their practice. Why then present masculinity as the unifying theme? Why not examine other associations between the artists such as their use of portraiture or self-portraiture?

The work of these artists does highlight certain stereotypical characteristics of Western or Anglo-Australian maleness. Notions of the anti-hero, destruction and self-destruction, pranks, labour, emotional vulnerability, self-deprecating humour, inadequacy, brotherhood and the exploration of macho culture feature in their paintings, photography, video and installations. So are they 'good boys'?

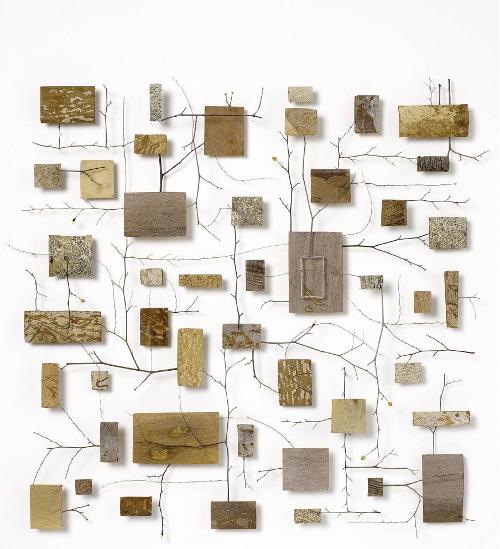

Marley Dawson celebrates and embraces masculinity, pranks, manhood icons and boyhood symbols in Parts and service (2008). In I am a good boy, he installed a pool table elevated by a scaffolding platform approximately two metres high. Pool cues, beer bottles, stubbie holders and ephemera surround the table, acting as references to sport and leisure and male bonding. Visitors are able to join the game, thus adding a degree of participation and competition. A nearby bar fridge is suspended out of reach near the ceiling. Similarly, a dartboard covered in darts is attached to a wall approximately four metres above the floor, making it impossible to play. Mitch Cairns explores concepts of Australian national identity and folklore in Father's Day (2007), Podium Finish (2007) and Look where they found, me dead on the ground (2007), which have distinctly religious and sentimental overtones. Cairns uses text and imagery to bring together past and present narratives, while his use of crumbling brickwork and coffins signify decay and loss.

Furthermore, Michael Moran, in his photographic self-portrait 1989 (brothers sleeping) (2006) examines the poetics of the anti-hero through an examination of brotherhood and camaraderie in Australian sport, with its consequences of death and tragedy. Here, Moran stands naked from the waist up, black text scrawled over his chest and his face censored – a powerful statement of the anti-hero. Pete Volich explores the banality of everyday objects and contexts of the suburban environment. In his slick photograph, Thoughts from the nap in an afternoon couch (2006), Volich constructs a fictionalised narrative situation in which the re-evaluation of identity comes from images of male clothing haphazardly strewn over an armchair. At first the work appears to be a documentary photograph, but on closer inspection the viewer realises clothes have been placed on the chair in the form of their owner's seated body. Volich's act of personifying material possessions results in a cool and ambiguous statement on individual identity.

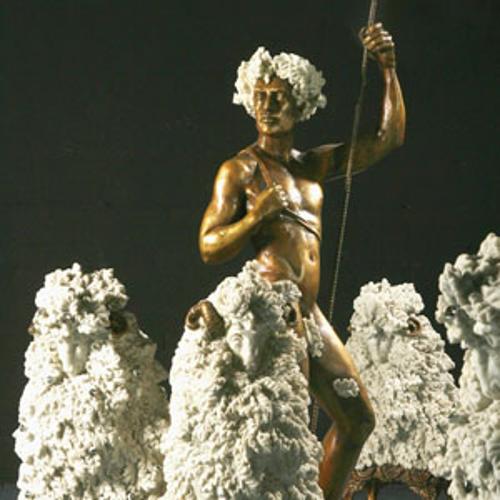

Ben Quilty, known for his iconic, symbolic and gestural paintings, exhibits yet another semi-figurative head floating in a void. This time Most Improved (2007), a reference to the also-ran prizes of childhood, is suggestive of the need to restore male confidence which has apparently declined since 1970s feminism. The clunky quality of Quilty's chunky slabs of trowelled paint is unfortunately just a little out of place in this context.

Routledge's curatorial premise is best demonstrated in the work of Todd McMillan, an endurance performance-based video artist, who examines notions of melancholy and vulnerable masculinity in a remix of the 1956 Elvis Presley song I love you. I want you. I need you. In the course of four hours, McMillan repeatedly says the words 'I love you. I want you. I need you.' directly to camera. This exhausting act causes him to appear breathless and fatigued, his distorted speech becomes incomprehensible, the repetition of the words diminish in meaning, yet his facial expression is one of sincerity, longing and sadness. The effect comes from hours of video footage spliced into just a few minutes film then played on a loop. The result is the artist's face on screen mouthing the unnaturally strange sounds 'ooohhh ahhhh yeeaappp weeee'. The repetition of these emotionally charged phrases produces a somewhat contradictory effect as intimate feelings appear banal, yet resonate with strength and humility.

Through these explorations of macho culture and male identity, the artists use themselves as subjects, or the methods of portraiture, to reflect, look within and examine whether they are or are not 'good boys'. Routledge's amusing title would assume, despite the pool playing, pranks, destruction, tongue-in-cheek humour, and emotional vulnerability or reticence, that in fact they are.