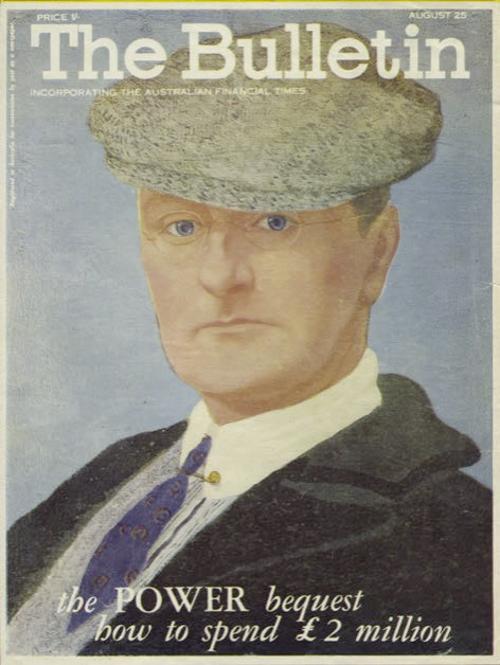

Art biennials (or biennales) have an uncanny knack of positioning art communities within wider cultural circles. Consider for example the run of Sydney Biennales of the later 1980s fixated on centres and peripheries to the point where one actually began to believe that Australia was indeed the ideal post modernist zone isolated by cultural and physical distance to the point where everything 'out there' was hyperreal or endlessly negotiable in terms of meaning and relevance. While most of the art assembled for these Biennales may now be forgotten, the fact that this theme or focus was considered of priority importance at the time says much about some Australian art communities' anxiety levels or self-confidence. So where does that leave Handle with Care the 10th Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art? As implied by its title the prevailing themes of fragility and concern were not surprising. But viewers lured by the prospect of artists tub-thumping about the environment, human rights issues and so forth must surely have been deflected by the ambient means used by many to express concerns. As curator Felicity Fenner warned at the beginning of her catalogue essay the exhibition would be 'negotiating the sometimes uneasy relationship between intellectual and intuitive readings of art.' So many of the works demanded such a reading that in retrospect the double entendre of the Handle with Care handle favoured 'art' as the item most in need of the white gloves treatment.

Taking a lead from Victoria Lynn's comments (2007 Auckland Triennial) about 'small gestures' of art catching us 'off guard' Fenner was clearly trusting in her selection of works to take her audiences on a journey, not so much through the landscape of contemporary dissent and concern linked to environmental and social issues but rather the strategies of different artists in continuing to make 'small' (or large for that matter) gestures in a time of global transformation. In deciding that none of her artists would have participated in previous ABAAs Fenner demonstrated courage that might have been misplaced had the works not delivered in special ways.

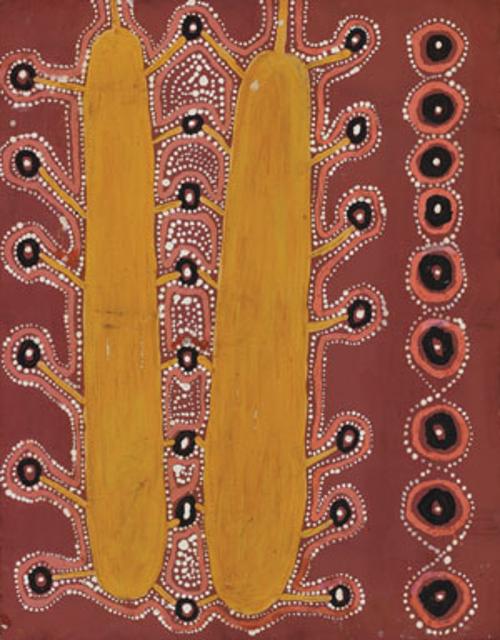

And that meant being able to address and communicate elusive perceptions about such things as being 'Australian' but also 'global', about living 'here' but also 'there', about seeing the 'big picture' in the smallest of circumstances and above all trying to define and value those things that define what it means to be human. At first glance, little of this was apparent. Social and environmental concerns elbowed their way to the front. An actual demonstration on the opening night (Upper South-Eastern South Australian farmers used the presence of the James Darling and Lesley Forwood's Troubled Water: Didicoolum Drain Extension installation to voice environmental concerns) made sure of that. The video works of James Newitt ('performances' by 'population transfer' Africans now domiciled in Tasmania), and by Warwick Thornton (an extraordinary cameo by a grand daughter protecting Nana) were readily accessible as explorations of cultural tenacity and possibly survival in hostile or foreign territory, as was Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan's Address, a 'home' constructed of notional 'Balikabayan' (returnee) boxes.

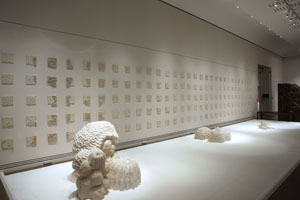

Ken Yonetani's Sweet Barrier Reef (a richly theatrical Zen-like garden populated with coral-like forms leached of life) and Tom Mùller's Liquid Empires (a series of bar-graph-like test tubes of water representing river levels across the globe) had plenty to say about global crises in water and reef conservation. But even in the straightforward act of engaging with Mùller's installation for example, it was apparent that it involved more than recognizing a visual metaphor for commonality of river systems and associated environmental issues. Throughout Mùller's practice it is the very act of coding scientific data that is a key focus; also people's capacity to be reassured and even mislead by such apparently objective systems of measurement.

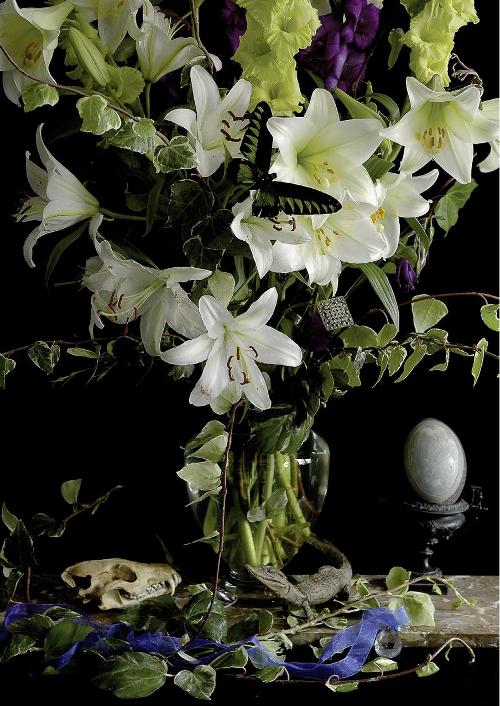

Similar subversive notes echoed in a number of works; the 'objectivity' of Gregory Pryor's translated, daily diary notes maintained across a two month period in Taipei, and Kate Rhode's ersatz Wunderkammern crowded with acrylic-faux creatures of multifarious hue, pattern and form. Bolstered by such works an overarching theme of alarming instability slowly emerged. In the materiality of many of the artworks lay coded references to the mutability of systems of recognition and response. Dadang Christanto's Never Ending Stories for example was composed as a floor installation of conically heaped cardboard rectangles, cut from used boxes. The random typography and cursory calligraphic gestures applied by the artist, suggested the tag ends of identifying lanyards ripped from the necks of hundreds of bodies. The work looked at first appearance like a scrap heap and in doing so embodied the right visual codes for depersonalised slaughter. Hossein Valamanesh's occupation of space nearby (Leave your shoes here), defying the tyranny of the museum's white cube by colonising a darkened place of retreat with jewel-like Persian carpets, joined Christanto's work and others in this reflective exhibition in gently asserting the primacy of sensory, sensed and imagined experience over conscious calls to the barricades of responsible, global action.

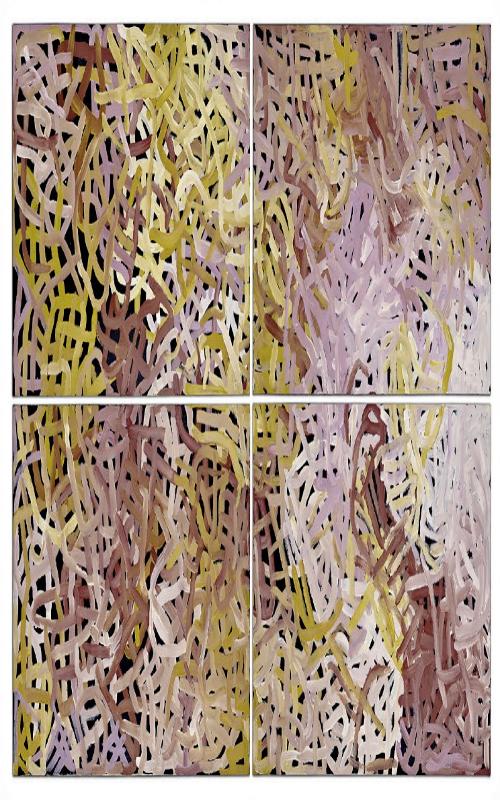

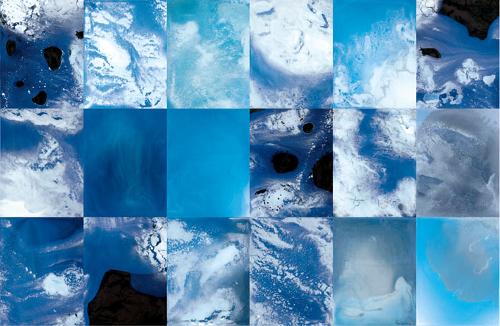

In the febrile intertwining of Bronwyn Oliver's organic forms, the catacomb-like interlocking of Darling/Forwood's bones of long dead mallee forests, the fragility of Mùller's threads of water held in thin glass veins, the brutal beauty of Lorraine Connelly-Northey's woven rusted barb wire O'Possum Skin Cloaks, the alchemic slurries of Catherine Woo's Blue Sky Project – make my day II, the risk-taking behaviour of Suzann Victor's Siamese twin-like chandeliers, the vulnerability implied by the fleshy pinkness of Guan Wei's heaven-seeking hominoids and the hooded eyes of Newitt's 'performers – lay the experiences that are likely to remain, long after one forgets the particular cause or issue.

With exceptions ABAAs have concerned themselves with themes of social responsibility, anxiety, uncertainty, dysfunction, utopianism and despair as if most artists and curators have responded to a peculiar Adelaide zeitgeist drawn from its geographical and cultural status as a 'retreat' from or an 'observation post' on the wider world. How interesting might it be to reconvene the curators of all previous ABAAs to reflect in a future Adelaide Festival forum on what all this might mean and how the ABAA concept might be best handled with flair in changing times.