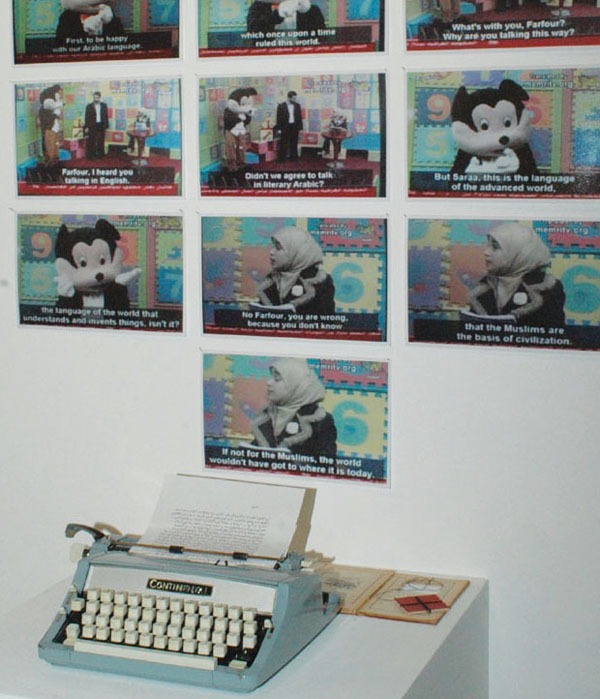

While many speak of the authority of the printed word, the allure of the book far transcends its mere containment of information. As a vestibule of hopes, dreams and the imagination, the book is an object of wonder that engenders a poetry independent of the printed text bound within. This made the challenge set down by curator Tara Gilbee in book project, for many, all the more provocative.

Gilbee, whose stewardship of the project ventured beyond the realm of curatorship and into collaboratorship, posted books to artists that she had collected and, systematically, mutilated. Receiving the remains of these books in the mail, each of the thirty-two participating artists were invited to create a new artwork that addressed 'the space in between' – i.e. the negative space between the body of the book and those sections that the curator had surgically removed with a scalpel.

There were some ingenious solutions to the curatorial brief. Chris Bond, at the exhibition's entry, constructed a complex work that joined the separated elements by converging lengths of line, like a Da Vinci diagram materialised. Similarly Gabrielle Brauer's Plutarch's lives was so much more than its listed medium 'book and paper' becoming, instead, a fully formed dinner jacket composed of paper mache. Paul Irving also took the path of relentless deconstruction, by transforming his book into a fantastical sculpture – a kind of telescope designed for peering beyond the physical composition of his 'untitled' book.

As a habitual paper-cutter, Kate Cotching was an obvious participant. Her work Bridge revealed an acute dexterity, turning her pages into visual poetry and the illegible narrative into real form and space. Martina Copley's book, open midway, became a canvas for dense, black charcoal: a solemn paean for a volume denuded of function, while Andrew Goodman transformed his pages into wild, organic vines, bursting from his book covers in demented, ornate and exquisite cascades of foliage.

Aloma Triester was among those who took a more literal route with her work Shredded suggesting an unfortunate meeting between her book and a food processor, pursuing the theme of book destruction with vigour. Tracy Sarroff's compendium 'Radiotransmision' became lost in a forest of electrodes and diodes, while both Penelope Hunt and Ash Keating attempted to reunite the book with its components: Keating literally sticky-taping the sections back in while Hunt, with considerably more guile, replaced the lost section with an image of what was missing.

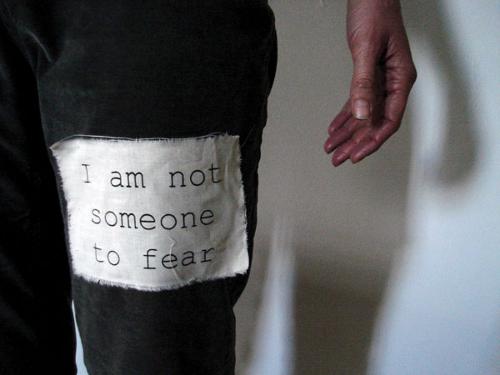

The most successful works were those that transcended both the curatorial stratagem and the formal aesthetics of their book: where the artist brought something entirely new to the project by considering the broader implications of the book as a subject of physical brutalisation as well as an art object – a use to which it is not typically ascribed.

Elizabeth Presa was alone in dispensing with her book entirely, presenting instead a series of photographs, capturing the slimy path of a snail across its pages. While the snail's literary dispositions are not known, it neatly summarised the investment of time that reading dictates. Mandy Gunn's concertinaed pages dissolved into a fictive transmutation of cloth and text, as visceral and sensate as these works came, while Greer Honeywill buried her book within the rafters of a skeletal house. The unknowable secrets of the book became locked away in the 'attic' of the unconscious.

On many levels the creative enterprise of this exhibition was unavoidably fraught, however as a wellspring of so many new ideas and potential channels of investigation, the Book Project was worthwhile as a means, if not always, an end.