Continual advances in biotechnology suggest that our perceptions of the human form could radically change in the future. Cloning and genetic engineering have the potential to modify and extend our corporeality, with profound implications for our notions of self. Such concerns are central to the work of emerging artist Alicia King, who utilises wet biology practices to affix cultured human skin tissue to glass sculptures. Artist-in-residence at the University of Tasmania's School of Medicine and former student of SymbioticA, King held her first solo show this August.

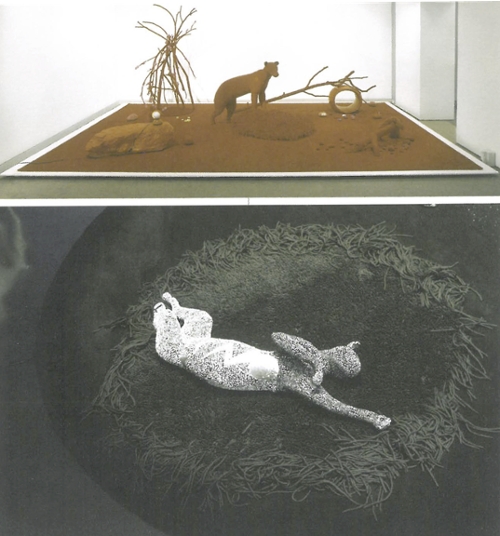

i'm growing to love you in Linden's Gallery 4 had two components. The first, a globular form made of foam and plaster, growing up the gallery wall to chest height, seemed like an adjunct to the more compelling sculpture on the adjoining wall. Incorporating human skin tissue the second work was a lumpen mass of black plastic, suggestive of a bodily lesion or growth, which sprouted two clear glass antlers. These antlers fruited a multitude of delicate blown glass skulls speckled with a curious pink substance.

Without reading King's artist statement you might miss the significance of these pink speckles. Dyed skin tissue derived from the he-la cell line, they originate from the cervical tumour of African American woman Henrietta Lacks, who died in 1951. Lacks' cancer cells, known as he-la, are uniquely aggressive and rapidly growing and continue to live on in labs across the world as a commonly used cell-line for research, contributing to the study of countless diseases. King's use of he-la is made poignant when you consider that, despite the millions of dollars the cells have made biomedical researchers since their discovery, they were propagated without Lack's knowledge or consent. The story raises some important ethical questions concerning the ownership and commodification of human body parts. King explains: 'The he-la cells are so significant because they bring the focus back to the individual, bringing a subjectivity to their abstract substance within the realm of the economically driven biomedical market.'

The potentials offered by new biotechnologies are creepy yet compelling. King plays on our uneasy curiosity with forms both monstrous and alluring, recalling a genre of films that include the Aliens series and David Cronenberg's Dead Ringers. i'm growing to love you envisions a future where biological advancements make life possible in the most unlikely of places and forms. King's work responds to a change in definitions of life and her inclusion of antlers emphasize the already ambiguous boundaries between being and non-being. Despite growing from the body, horns, like hair and fingernails, are considered to be at an in-between stage of living and non-living. King's thought-provoking work anticipates a blurring of states that will force us to re-assess what it is to be alive and human.