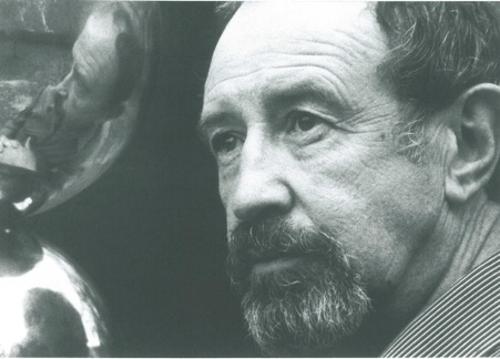

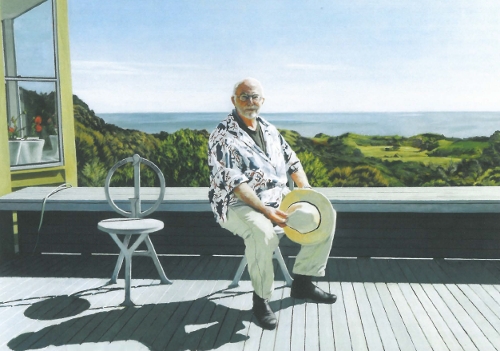

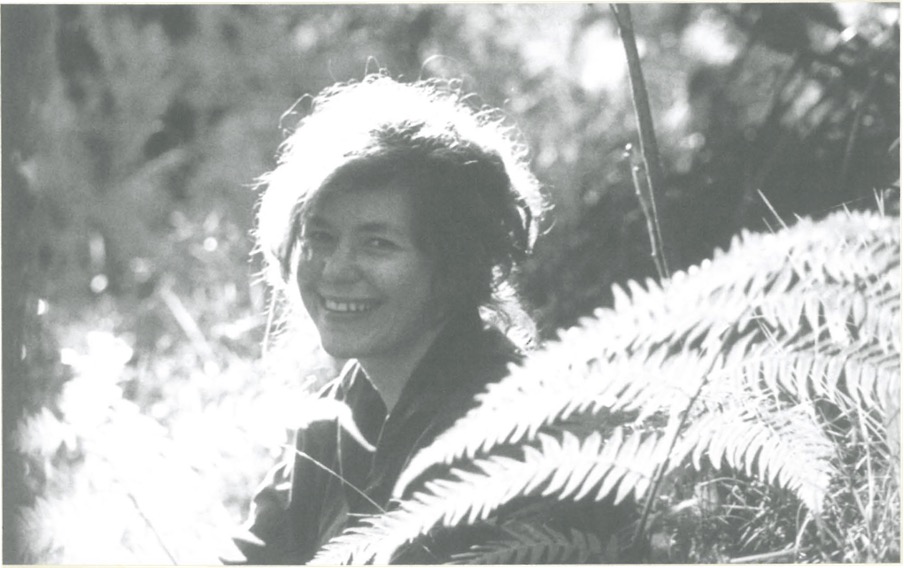

Joan Kerr: A pictorial biography 1938-2004 James Semple Kerr, published to accompany Joan's papers to the National Library of Australia 2006.

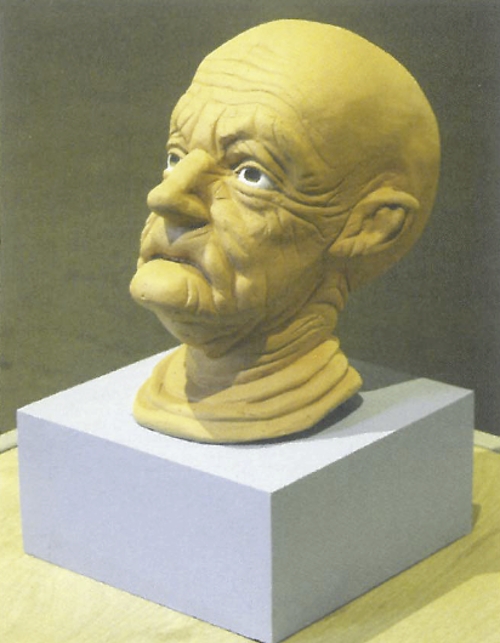

These were not gentle, modest, whispering, shades inhabiting some semi-mystical Celtic twilight romantically attuned with nature, but tough, strong and difficult ...

Art historian critic, essayist, heritage consultant, the late Joan Kerr was writing of the Irish-Australian women who passed though the Hyde Park Barracks wondering whether their presence was effectively mediated into the Irish Famine sculpture. Furthermore she added 'we don't want to remember them solely in piety as what has melted away in dismemberment and loss'. Ironically Joan could be prophetically setting out the appropriate moodscape for her own memorialising. In the words of her husband who has compiled a partisan and intimate memoir of this distinguished artworld figure, Joan had 'a natural capacity to prick pretension and kick against the pricks of perceived injustice ... Perhaps there was something of her Irish-Australian heritage in her – but whether larrikin or crusader, or a combination of both, is unclear' (p135) In an Australia that is too often filled with the mediocre or prudent time-servers and boot-lickers across the whole political spectrum, forthrightness was not the obvious way to win friends and influence people.

Joan Kerr's career prompts consideration of the nature of fame and validation in Australian art. More than any one else she established viable alternatives in debate around Australian visual culture, by indicating the narrowness of the canon and the merit of that which lay beyond – the art of the ordinary, the unfashionable the devalued, excluded by race or gender, the non-A-list. Hence the relevance of Joan to a project devoted to documentation of the often overlooked and taken for granted. Whether it was her gender, her 'outsider' status, or because although clearly a player in the system, she was in the end not the most effective, cynical or self-serving of system players, a solid and proper validation of Joan's contribution has eluded public memory. Undoubtedly her relatively premature death contributed to her lack of institutional hagiography. Moreover Joan was, to some degree, denied some of those high status and highly visible appointments and honours that are cumulatively heaped on Australian academics of perhaps more predictable trajectories.

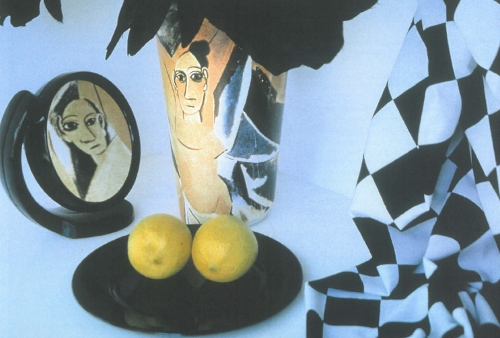

James Kerr's account may at first disappoint in its mostly personal focus, although a scholarly anthology of essays is coming out next year. However the pictorial material is unfamiliar, highly evocative and striking and will be a major point in recommending this book to those beyond Joan's personal and professional circles. Moreover the clearly personal slant on the material also resonates with recent debates in essays around the act of writing Australian biographies, that are raised by academics and public intellectuals such as Cassandra Pybus, Jenny Hocking and Inge Clendinnen. These debates centre upon the constructed nature of biography, inclusions, omissions and the varying boundaries and definitions of public and private. James Kerr's account prompts consideration of all these formal and conceptual faultlines. Accounts of ongoing poor health, that Joan rarely aired publicly, are humbling, as too her unsettling encounters when a child with the darker side of gender relations in traditional urban Australian culture. Yet the merits are not only personal, for although the fear of being subject to the laws of libel when writing non-fiction of the recent past has sanitised the manuscript, the book offers much about the workings of certain segments of the artworld within the close networks of friendship. Equally fascinating are the insights into the academic system, Joan being often an effective insider for whom support and opportunity came more frequently than for many others. Joan's high achievements at the University of London and York in the 1960s and 1970s suggest that academic narratives of merit finding reward could have had some basis in fact. However Joan's unwillingness to play the game or accept currently preferred convention, meant that these opportunities were consciously or by happenstance withdrawn.

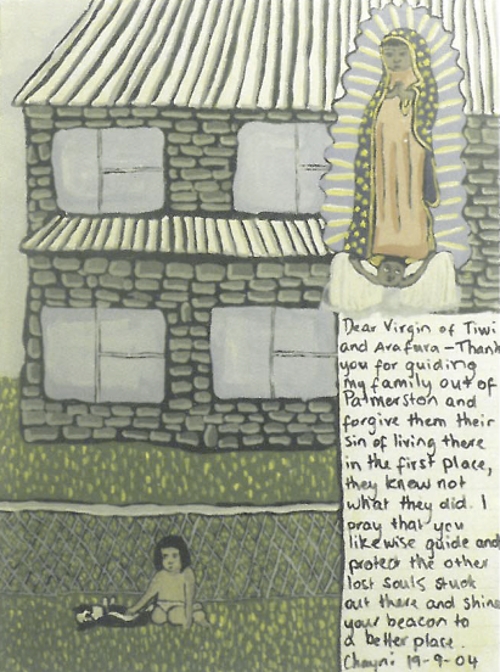

Despite the fear of the law, subtly James Kerr's narrative strays into unfamiliar territories, the remarkable and much disavowed universe of the Latham diaries, an unstable Australia riven by petty personal anxieties and conflict. But whilst kneeling and swallowing may be familiar items on the order of the day for most of us, Joan never swerved or compromised. Thus she had no reason for the bitter melancholy rhetorical flourish of early twentieth century Labor premier of Victoria Tom Tunnecliffe's reflection that his political life was thoroughly ridden with corruption, noting in effect that the compromising poison of loss of ideals was spread by the spider kiss of his mate – the ALP as Portrait of Dorian Grey – or does this reflect upon the nature of Australian social and cultural life per se? Focussing Joan's ethical and cultural universe, it appears that she had a deep appreciation of and ironic sympathy for the moralising pictures of the Victorian era. Her career as art writer began and ended with Victorian art and she combined the imperious matriarchy and public power of the Queen with the raucous grounding and gregarious pisstaking of Joan's own putative – but unspoken – Islander heritage, the latter maybe also providing a wellspring for her notably practical deployment of feminist power. Joan's own speculation on her origins are typical of the unfamiliar and pungent details that will make the Pictorial Biography compelling and valuable for later generations.

She was an effective spokesperson for contemporary artists, (many of whom were friends), as well as younger women, students and junior staff members' rights and indigenous issues. For an example her summation of the whitebread nature of the 1988 Bicentennial in Artlink not only identified the emperor as naked but also as the classic 'short dick man' of a soon to be popular song , entirely prophetic of the next decade of art history in the acknowledgment of the place of Indigenous art in the framework of historical memory. Not only is this Pictorial Biography engaging and warm as a portrait of a personality who did so much to challenge the mainstream definition of art, but it documents an important early supporter of Artlink. The biography also embraces old Artlink themes of seeking material off the expected Sydney-Melbourne axis of power – with a strong Queensland alignment – and also an in-principle support for a broadly defined wellness and quality of life.