There is a tradition of merging art with life in late modernism that goes back to at least Claes Oldenberg's 1960 installation called The street. Oldenberg had transformed a Greenwich Village gallery into a rough facsimile of a slum perhaps only two blocks away. Ilya Kabakov in more recent times has similarly transposed spaces from the Soviet Union to a New York gallery, seemingly real, but nonetheless embellished by imagination.

The installation called The second of the ordinary practices by the New Zealand artist who calls herself et al is firmly in this tradition. The real, the simulated, and the imagined seem to blend here into an ambiguous but nonetheless coherent commentary on the arbitrary relation between ideals, ideologies, and the repressive use of power.

Enter the IMA expecting polished floor and pictures on the wall and you're in for a surprise. The installation space at first most resembles a construction site you might have just passed in the dusty streets of the city outside. Chain wire barriers with concrete footings, and with the local hirefirm publicity panels still intact, enclose what look like a row of port-a-loos.

These enclosures are somehow both sinister and ordinary. Look closely inside each cabin and you can see a motor, transformers, unruly wiring and grinding pulleys that come to life with a hideous sound to wind the little cabins in tortuous jolts along a cable up and down each enclosure. Inscrutable graffiti-like scribbles on the inside wall of each cabin could be instructions, mathematical calculations, or pleas for help.

The room is semi-dark, the walls are painted black and you are partly blinded by harsh spotlights. At the end of the room is a big screen onto which are projected a seemingly random series of quotations from various texts: pronouncements about art, injunctions to breed an Islamic super race, statements about the treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo bay, philosophical reasoning, ascetic disciplines of the body, formulae for torture. These texts are read by the awkwardly precise, alternately male and female, voice of a computer text-to-speech program.

Although there are some holes through the chain wire, only one of the enclosures is easily entered and escaped. In it, a steel post acts as a pedestal for a childish little sculpture of a mule high above our heads. Artist/s et al also known as Merylyn Tweedie, periodically adopt various pseudonyms/collaborators including Lillian Budd, Merit Gröting, Blanche Ready-made and P. Mule. So perhaps the mule is a kind of self-reference. Art might be the only escape from ideology.

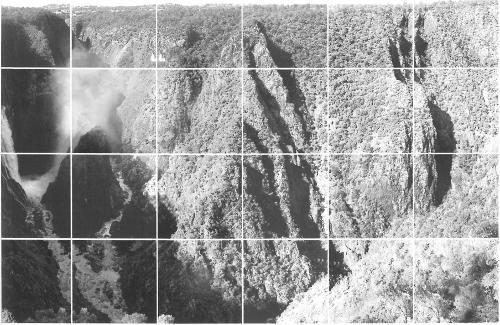

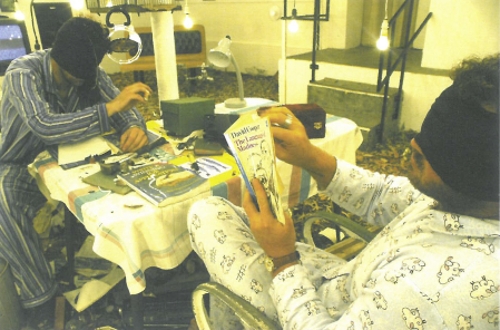

In another adjacent space, we find what seems to be a control room. A computer model of the Baxter detention centre is projected on the far wall. A well-used desk bearing only a computer screen and keyboard that look to have seen better days contributes to a cold, remote, and technological but somehow archaic, atmosphere.

The function of these structures is not innocent and neither, in the terms of this installation, are we. We are reminded that the same means and rationales that make our lifestyle possible are employed to control and persecute and even torture.

An earlier version of this work called The fundamental practice represented New Zealand at the 2005 Venice Biennale but clearly it lends itself to site-specific adaptation. The connections it makes are telling. For example, I have since found out that the Baxter detention centre was in fact built by the Brisbane-based Theiss corporation. Western Economies tend to flourish on the back of war contracts; no wonder the lone chair in the control room is turned slightly from the table inviting each of us to occupy its ideological space.