'Art must.. be autonomous, self-reflexive and resistant to wider social forces. If it engages with the materials of popular culture, it necessarily reframes them, distances itself from them...'.

Rex Butler on Rosalind Krauss, catalogue, new objectivity, Karen Woodbury Gallery, 2006

It is odd when two separately curated exhibitions appear so aesthetically alike. Just months prior to Linden's Reflections in a Golden Eye, some extremely similar works appeared in the engagingly titled new objectivity at Karen Woodbury Gallery. Including works by Jonathan Nichols and Michael Zavros, Butler's accompanying essay claimed that they were '.. no longer really works of art' because they were '.. pure content without form'. And not only did they '.. not seem particularly meaningful for the artist' but also '.. the medium of painting does not provide a privileged space from where we might think about them'. He continues by correctly stating that the images could have been in any medium as they were mere simulacra – of the 'real' or of any image in any medium. This is an apt critical response to where art in these times is in danger of heading.

In light of this proposition, and what seemed a remarkable aesthetic coincidence, the Linden exhibition – which the catalogue essay outlines as being premised on the use of traditional mediums to present 'new perspectives on portraiture and the landscape that in return reflect.. the complexities of the time in which we live' – compelled me to take a closer look.

Apart from one work of a (presumed) photograph of a girl with her tongue sticking out, Jonathan Nichols' Paradise (2006) series at Linden was a shift from his flat, pastel-toned works. While his artist statement acknowledges that 'painting is complicit in image-making', and while signs of painting were increasingly evident, there was also an engagement with 'social forces', particularly in a black and white sketch of a 'busy' couple on a park bench, girl's legs astride her partner, and a woman sitting beside them. Altogether, Paradise seemed to suggest a 21st Century perspective of late-19th Century themes around leisure – walking on the beach, kissing in the park, a couple at a party – and perhaps an exploration of the influence of technology on figure-ground composition (presented from slightly above, slightly below, or front-on).

On the other hand, Butler's critique resonated in response to Meilak's hyper-real watercolours of catwalk models. As Gellatly states in her catalogue essay, Meilak art-directs his own fashion parades 'to investigate the allure of beauty and glamour'. Though delicate, his paintings were like studies of Zavros' hyper-real oil paintings of the same subject, so presenting his 'parades' as paintings – and in double – seemed almost meaningless. Perhaps they would have more resonance as performance, or video. Otherwise they seem to reflect a paradox between the equivalence of fashion and painting: 'painting is fashion.' (Butler)

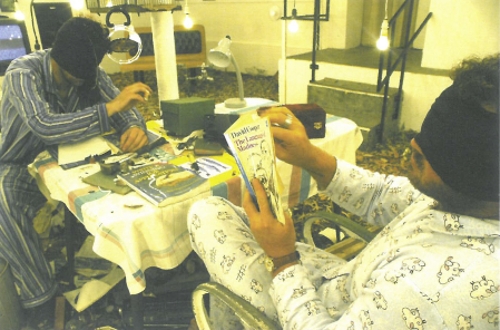

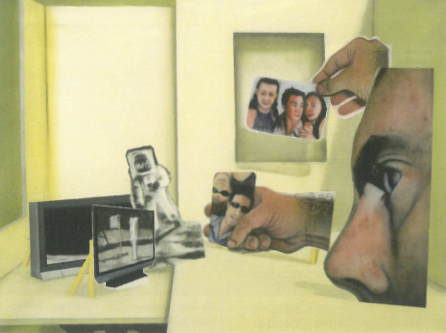

The most interesting works in the exhibition were by Lynch. Through juxtapositions of scale and perspective, his surreal images comprised painted grounds of interiors that operated as dioramas for collaged objects and body-parts (his own) floating across the canvas. Based on dreams of friends in which Lynch has featured, the combined references to studio or art practice (reversed canvases, easel-legs, etc), art history (Malevich's black square, the cubist-perspective of a cake, etc.) and 'materials of popular culture' (jeans and thongs in Carrying my birthday cake... 2006; an empty television set, screen separated and canvas-like on an easel with images of the 1969 moon-landing in Watching the landing on the moon on tv... 2006) were used to construct this multiplicity of self-portraits -– a psychoanalyst's treasure trove.

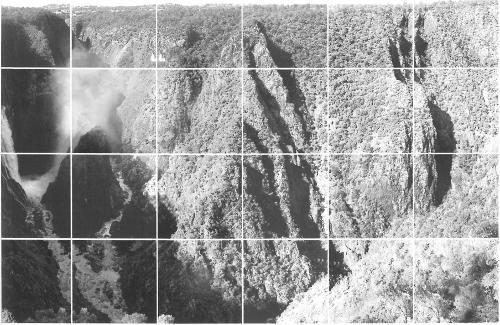

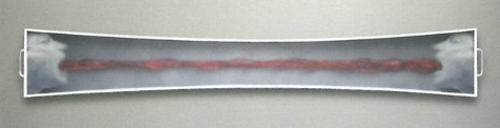

Along with Ussher, whose large-scale, intricately rendered drawings represent aberrant landscapes after human intervention, Lynch used a traditional medium (and technique) with imagination. Similarly, popular culture references were 'reframed', but as part of their respective themes and in relation to the 'complexities of the times in which we live'.