In the middle of the Sydney Biennale's Zones of Contact Symposium After the Event: Rewriting Global Visual Culture, Franco Belgiorno Nettis died. He was 92. In 1973 he established the Biennale of Sydney. Some of his last hours he spent in his cherished garden, a hemisphere away from the techno-buzz of its fifteenth incarnation.

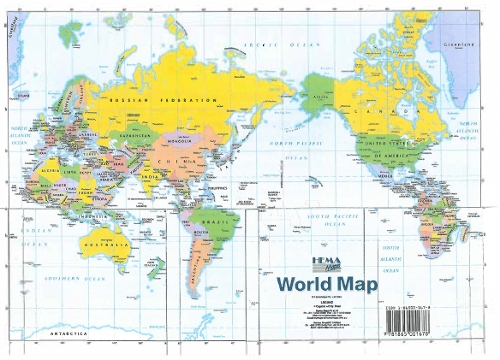

The founder of Transfield construction company had said 'engineering is an art and art is engineering'. It sure is. Zones of Contact comprises 85 artists and collaborators from 44 countries film, symposia, artists' talks and performances in sixteen venues over three months.

The credit for this particular feat of engineering is generally given to its director/curator Charles Merewether. Most articles about this biennale begin with his vision as the way into the show, he is – quite literally – on a screen at the entrance of a major venue; his pensive pronouncements play endlessly. It's soothing, with this expedition we're in experienced hands. Indeed, the word curator has its roots in the word cure, now I'll add orator. It's a heroic, authorial model but a tangible and successful one. Curator as hero?

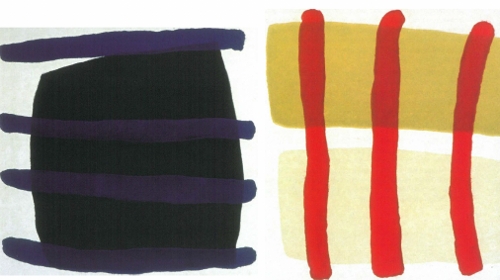

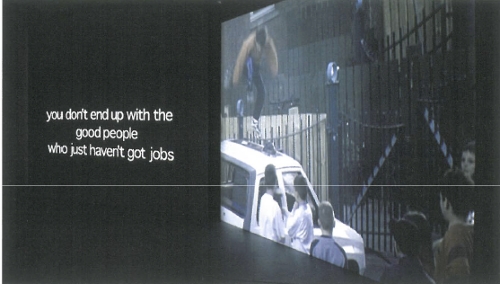

Zones of Contact is a clean, broad biennale. Not much messy domesticity. Lots of screens. Lots of photography. This show privileges documentary. As I cruised through venues as though skating on a surface, I had to ask: Is documentation contact? Is the post-post-modern condition forever being out of the contact zone? Or is the screen the closest we get?

I became the flaneur, skating across a surface of other peoples' experiences, their tragedies, struggles and memories. This isn't altogether as empowering a feeling as the omnipresent flaneur is supposed to feel. For a start there's invisibility and then there's impotence. I've never felt quite comfortable with the voyeurism of film; spying from the dark safety of a curtained room, feeling manipulated yet being unable to participate. Though the very point of this type of documentary is the impact of globalisation on the individual, so much of this work falls back into what we are assailed with nightly from multinational corporations like CNN. It begs the question: Does repackaging ancient intractable conflicts such as Palestine and Lebanon, India and Pakistan and wars on 'terror' really alter them? Moreover, does the personal ever transcend it? Spectacle and trauma seem so built into the very act of documentary that we search for it. Some works – such as Hayati Mokhtar and Dain-Iskandar at the MCA – are beautiful until you read what they represent. At one exhibit at The Australian Centre for Photography showing Sharon Lockhardt's 19 large simple photographs 'addressing American childhood', someone inscribed the visitors' book with 'a pedophile would love this show'. You can't enjoy it after that. Be it the medium or the message, aside from a few feel-good pieces, trauma rather than joy or whimsy characterise this biennale.

Is this a cohesive show or a idea stretched over a lot of diverse objects? What is my contact with this work? I have yet to be seized by the immanent purpose of them. Isn't watching a DVD only to be in the afterglow of an artistic encounter that has taken place elsewhere?

In keeping with my post-modern 1990s education I challenge the old 'centre' and 'migrate' to the 'periphery'. I leave my comfort zone in search of some contact. Onto the rhizomatic railway, past Villawood and Macquarie Fields, out to a demographic centre. I got lost.

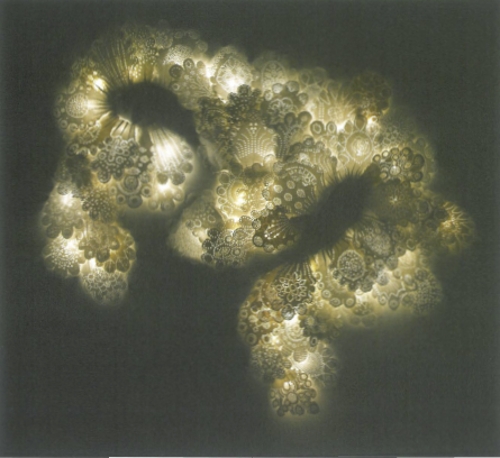

Through kilometres of carpark past skaters on school holidays, I find the Campelltown Regional Gallery. I was alone in another city in a dark room. Maybe my curmudgeonly defences were down but away from AGNSW, Pier 2/3 and MCA, orbiting the satellite shows, some of this work reached out to me. In Campbelltown, Sejla Kameric's Dream House Story seems to be just that. A DVD image of a house projected onto a large scrim seemingly floating in the centre of a dark room, its background morphs from day to night; landscapes, clouds, stars etc, it undulates gently to a soundtrack of breathing. This diaphanous two-dimensional idea hangs delicately in the air, filling the room as it moves; it is everywhere and nowhere; intangible and somehow independent of the geopolitical.

At Artspace The Rotators by Ujino Muneteru is the standout piece. Not only is it big loud and bright but it makes the familiar something else and mean something more again. Industrialisaton flooded Japan with cheap technology which, he claims, almost usurped traditional respect for domestic objects yet it lingers in an idiosyncratic fashion; blenders, lamps, the windscreen wipers and lights of an entire car are connected to turntables, the stylus arm amplifies modified LPs. Someone remarked as their husband traced the mass of wires 'this is a boysy work' meaning, I suppose, the How? is as important as the Why? I laughed out loud, a point of contact?

Tucked away at Sydney College of the Arts gallery is a flea-market from Kazakhstan. Well, actual fragments from the jumble of 24 trading tables are placed above photographs in which they appear, like witnesses, in the ordered jumble and below each is a quote from a vendor, a plea to purchase. At once these are moving and funny, juxtaposing the arbitrariness of value, the silliness of these trinkets with the serious background of a collapsed economy which devalues not only the meanings of objects but social interactions.

In another room, a DVD Fikret Atay in Tinica 2004 sets old margarine tins up as a drum kit on a cliff on the fringes of his hometown, drums them into a frenzy and kicks them over the precipice. Why does this simple act resonate? For a moment those battered old tins became something else. It is this charge, this alchemy that makes biennales important: they can activate the ordinary, repackage the junk that accompanies city life. The long clattering train trip home was more rhythmic now than before, trash could be music and the supermarket a web of global versus local; even nihilism seems to have a point.

It's humour and wryness that I seek in these shows and there's a bit of it about, mainly in the form of the few huge crowd pleasers in the major venues. I also ask of biennales, do they activate or light up the city? If the buzz of the next generation of curators and writers jumping aboard the biennale bandwagon is any guide, this one does. 'A World of Art. Here. Now.' proclaim red banners on a main Sydney street. Where? Well you have to look for it and use your imagination, forget the last four Sydney [something]Festivals this year, ignore the maps, get the handbook, read the catalogue, get a train timetable, take a jumper, know something of global conflicts, repeat profound title a few times and&. duck behind that black curtain.