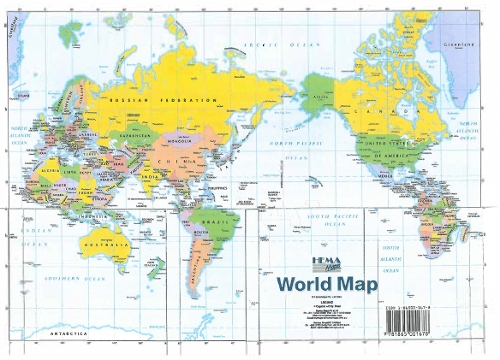

When in the introduction of the exhibition catalogue Dr Charles Merewether, artistic director and curator of the Biennale of Sydney 2006, defines 'Zones of Contact' as a framework and organising principle, he allows for a multiplicity of meanings 'in terms of mapping, of place and locality, of surveying and surveillance, but, equally of the architectural and forms of occupancy and segregation' to exist within the exhibition, which includes a great diversity of artists (85 from 44 countries around the world).

In many ways its intended impact is much greater than just being the biggest assembly of international art in Australia. The exhibition Zones of Contact is a certain breakthrough, and probably constitutes the first major 'non first-World' Biennial event to be held in Australia.

In fact the topic Zones of Contact is explained by the curator: 'In each case these zones constitute different discursive patterns, with their own rules of operational and accompanying values'.

In the catalogue essay he sees the idea as two-fold: I would say that the first is curatorial, as he defines it as 'specific places to enter the exhibition, and the site of encounter, correspondence and departure, following the route taken by the artists'. The second is a more general one, as he spots the proliferation of the term 'zone' in our times (e.g. war zone, border zone, free zone, trade zone, west zone, east zone etc). Many of the featured artworks refer to the temporal dimensions of those zones. The crossing of the 'Zones of Contact', the discovering of the new zones and rediscovering of the ones we used to inhabit, provide a strong foundation for the show.

This biennale, which follows in the footsteps of other grand spectacles of our times, deals through its thematic approach and structural framework with issues and conflicts which can be generally seen through the prism of globalisation. This type of curatorial approach is frequent in today's art world. It is one of the results of Jean-Hubert Martin's seminal 1989 exhibition Magiciens de la Terre at the Centre Georges Pompidou. Yet, it is hard to believe that Zones of Contact could do for Australia what Magiciens de la Terre did for Europe. If nothing else it is a changed world today and we have all become more global (through TV and the internet at least).

In the terms of its ambition, though, I would rank this exhibition as one of those mega exhibitions, among the many, which deal with issues that are widely termed as globalistic. Together with Magiciens de la Terre, we would inevitably have to compare it with Catherine David's Documenta 10 from 1997, Okwui Enwezor's Documenta 11 (2002), Harald Szeeman's Venice Biennales of 1999 and 2001 and Francisco Bonami's Venice Biennale (2003).

Generally, exhibitions that problematise issues of displacement, identity, and globalism cannot get away from geo-political and socio-political realities, bringing up other subject matter ie, the artistic interpretations of day-to-day events. Indeed, the displaced artist, as a symbol of a displaced community, has become an ontological and epistemological position. The terminology used refers to the emerging new discourses, and to the importance of language in interpreting and dealing with these discourses.

It seems to me that even 'home', as the strongest of all of the relevant words, isn't sufficiently strong to define identity in today's world. We are certainly made aware of complexities and of antagonisms of various kinds. In such a situation, we must ask ourselves: Does a certain new quality of disorientation emerge?

Juxtapositions of displacement are very strongly shown in Calin Dan's almost surreal video Emotional Architecture, which certainly tells the story brilliantly. However the curator's explanation that the work looks at the socialist architecture of Eastern Europe is much less convincing. 'It is very much about the legacy of the architecture, the very oppressive architecture built under the dictatorship and living in that & So you're living in a sort of residual legacy of a dictatorship, trying to forge a democracy.' One wonders when it was that the Modernist project in Europe was renamed 'Socialist Architecture'? How is this different to the same sort of buildings, built in the same time period in the west of Europe? Are they to be renamed as 'Capitalist Architecture', or perhaps – it gets even better – we should use the term 'Democratic Architecture'?

It is also worth noting that 'the location' where contemporary art is created has become one of the key elements to consider when curating a Biennial, only in a reverse order. The 'location of the art producer', which once worked against the artists in the second and third world, has now started to work in their favour (strange how this cold war terminology is still understandable, even though we have practically lost 'the second world' in the past 15 years).

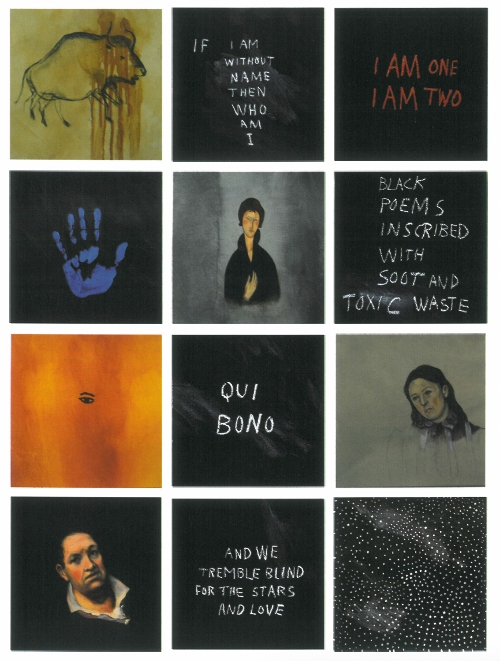

The Belgrade-based artist Milica Tomic has had very good exposure across art venues in Australia in the past year. Firstly, at the Experimental Art Foundation in Adelaide (November – December 2005), then in February at Artspace, Sydney, and finally in the Sydney Biennale in June with two works. I am Milica Tomic (already presented at the EAF), and Container (a newly commissioned art work for the Biennale). I am Milica Tomic is a seminal work about identity, centreing on issues of responsibility, political violence, nationality and identity, with particular attention to the tensions between personal experience and media-constructed images. This is a personal meditation on the historical, political and religious overtones of building identity through language. The artist stands before us in a white slip and starts to speak: 'I am Milica Tomic. I am a German.' She repeats this 64 times, substituting different languages and nations each time. For each sentence a new wound appears on her body.

Even more so, many of the exhibited artists did 'represent' the diaspora, as many originally came from the second/third world countries, but live now in the major western cities (e.g. Mona Hatoum, Calin Dan, etc). This enhances the 'nomadic' approach but raises questions whether these artists can genuinely 'speak up' in the name of the countries from which they originally came. Here I must add that, in fact, many of those who still reside in their countries have been hooked onto the Biennial and Artist-in-Residence circuit, transforming themselves into some species of permanently globe-trotting artists.

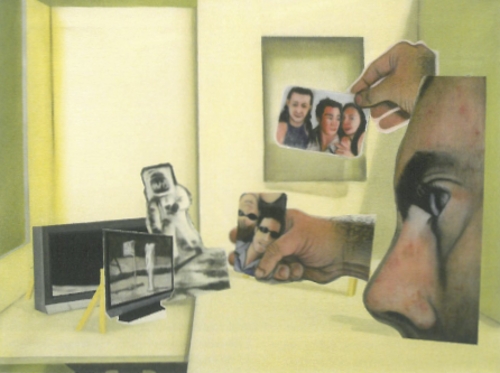

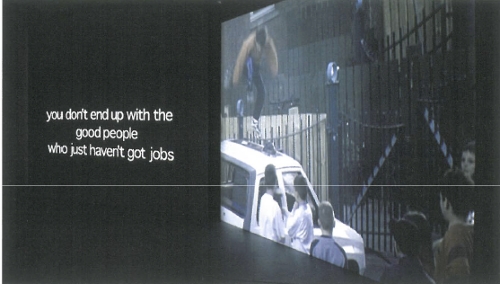

The often used term terror(ism) and accompanying revolutionary commentary and comprehensive border realities seem to prevail in accordance with our times. Jayce Salloum's installation 'Untitled' combines first-person interviews that centre on survival, resistance, disposition and various levels of 'dialogue'.

It seems that the first world/third world dichotomy is gone forever from the Biennale circuit, although the postcolonial arrogance is still very much present in the world of art fairs and, generally, wherever the exchange of money takes place. (I have yet to see how the symbolic capital the third world artists have painstakingly acquired over recent decades will be translated into hard currency.)

But substantially, how has the art of today qualitatively changed? Has a new subject been born? Hardly. What are the conceptual categories used at the Sydney Biennale? We see that the concepts employed fall into various categories such as: Borderline living; memories, which are personal and collective; the conscious and subconscious; globalism, paradigmatic of transformations of world society; and war. However, despite being potent with political content, we do not see this exhibition as 'political' (in this respect like many exhibitions of the last two decades). It seems to be no more about politics, or ideologies, than about conceptual practices. How then does one read the presented artworks, lacking the experiences in which they were created? One couldn't say with certainty. We could be certain about one thing. The aesthetisised marginal position has certainly become one of the familiar tropes of globalised art. So have antagonisms, power and limitations of identity.

The multiplicity of possibilities – of meanings, understanding and communication – contribute to Zones of Contact being a world-class event. The political and ideological strategies that are served by the Sydney Biennale represent an opening up of Australia to the art practices of numerous cultures around the globe.

The aim of the project was in fact an ambitious one. The exhibition did indeed concentrate on artwork appearing in different cultural zones of the third millennium, and shared an underlying tone of presenting to us the power, limitations and metaphors of visual imagery. Nevertheless, I find this conception of staging art events – with a strong academic thesis standing behind them, and yet with modest curatorial input in regard to the central cohesion and aesthetic articulation of the exhibition – as highly problematic when it is dealing with no less an order of concepts than identity, zones of contact, and issues of globalism.

Did the Sydney Biennale present us with new cultural visions? The answer would have to be no, but then again, is that the role of a biennale? Has the exhibition challenged, or been able to transform the ways we understand art and its role in today's age, by travelling through the various geographic latitudes? I would say not, for there was no firm structure which allowed us to do this. The lack of curatorial cohesion means that at times the exhibition seemed like a kaleidoscope of world images, aimed at merely intriguing and pleasing the audience.

On an ideological level the Biennale shouldn't just be entertainment at a higher level. It should serve as a focal point which will promote the far-reaching transformation of society. Ideology, theory and practice of images, the codes of visual language, and the philosophy of mind should be explored. It should be the biggest platform on which the production of ideas, and forming of memes, occurs.

Finally, governmental strategies for the implementation of cultural policies in Australia and elsewhere have to take into account the effect which these mastodon exhibitions have on overall processes in arts and society. The world of today has indeed become very different to the ideas of the first Venice Biennale in 1896.

This edition of the Biennale was probably better funded than at any time in its history, but it is still very poorly funded compared to major events of a similar calibre in the rest of the world. (Venice, Documenta, etc.) I think that if the Biennale is to be one of the leading hubs in the world, or perhaps even the Asian region, we must certainly support it to a greater extent.