It is almost impossible to write about Neil Roberts, because it is still impossible to believe that he is no longer here with us, but was killed so tragically on March 21 on a railway track near his home while, as far as we know, trying to save his dog, Siddha, during a morning walk. It would be much easier to step aside from this painful task. Yet, that is just the point – Neil Roberts never stepped aside from either the closest connection or the smallest link, the most obscure relationship or fleeting moment of speculation or wonder. He was warm and wise, imaginative and thoughtful, ethical and critical, funny and provocative, loyal, compassionate and loving. His death may well have been the result of a probably unconscious and automatic demonstration of responsibility. He is mourned by his wife, artist Barbara Campbell, his parents Val and Mert Roberts, and their family, and the many, many friends and colleagues who counted him as a special friend. On 27 March, hundreds of people gathered in Canberra to share their memories of his life at a celebration organised so perfectly by Barbara, and Neil's brother, Michael.

People in my kind of job collect information about artists in the way Neil collected objects for his work. And I've brought Neil's file home to try to write these few words. Leafing through half-remembered papers, wondering how quickly the years have gone, I am humbled and profoundly moved by this one record of his life over the last 15 years, documenting as it does, what must be just a few of his thoughts, hopes, plans and observations, as well as the many perceptive observations of others. It is a file that records ideas, interchange, exploration, wonder, connections, juxtapositions. How can it be possible that this very special person is no longer part of our lives?

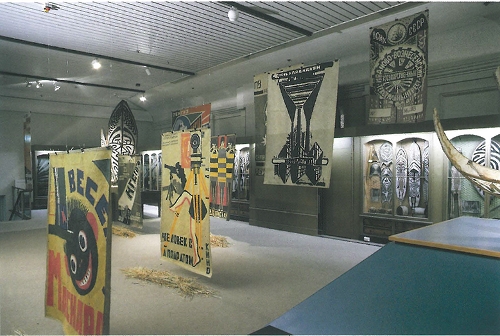

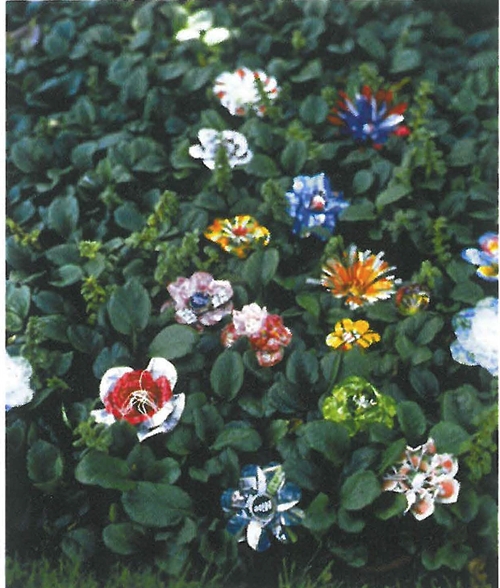

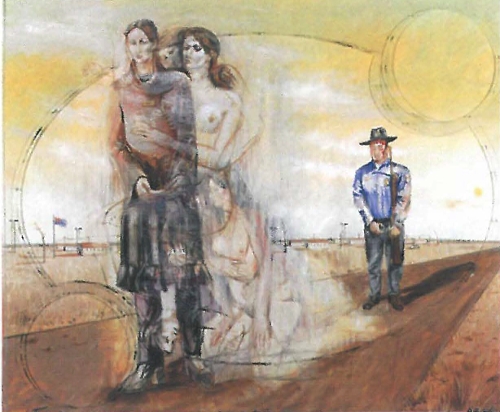

Neil Roberts was born in Melbourne in 1954, into a close family, with a father who was 'always making something.' He trained as a glassblower, and also spent some time on the road as a musician, but over the years his interest in tools and the physical process of working with materials saw the development of objects, installations and commissioned public artworks that were based on interactions with existing objects and the meanings they convey as part of human exchange. Oil-cans, jam-dishes, chisels, football bladders, boxing gloves, words from poems, trowels, glass tubes, neon lights and even water irrigation systems were realigned to combine their previous functions in what has been called 'a kind of intellectual recycling', usually to explore some of the contradictory perceptions of masculinity. Look at some of the titles of his exhibitions and individual works: Addressing the Wounds, The Plait, the Tatt and Baudelaire's rope, Tiny Idols heaped in piles, Suicide of the hands, Pause in the time of weariness, Things in the state of belonging, Dew mixed with sweat, Bruising, Breath. These are expressions of intimacy and exploration between ideas and objects, memories and questions, people and their lives.

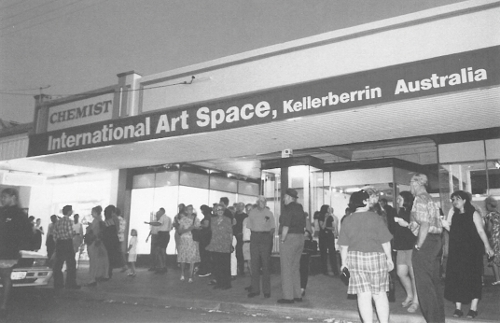

He was an articulate speaker and perceptive writer, a talented teacher and an excellent organiser who like to work with other artists. He was a good husband, son, brother and uncle – a good man. His fascination with collecting tools and well-worn objects that displayed characteristics of a previous owner's use, also ran to a talent for recognising those similar treasures that would appeal as gifts to friends: always surprising, always just right. Everyone has a Neil Roberts 'gift story'. After moving to Queanbeyan in 1983, part of his factory/home was opened periodically as the Galerie Constantinople art space for exhibitions and performances. He also co-ordinated the 1995 Canberra Sculpture Forum and my file shows the newspaper clipping (with photos) where despite being chased and sprayed with glue he enthusiastically dealt here with 'Monarchist rushes to clothe nude Philip and his headless queen.'

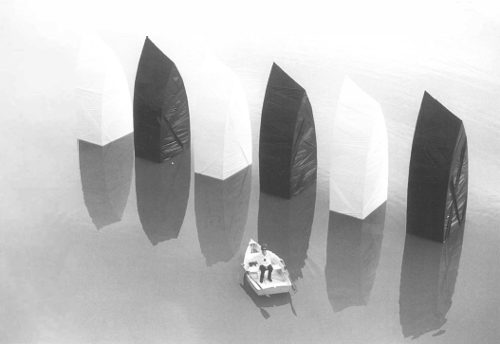

Neil Roberts had a number of solo exhibitions, the most recent being a, so timely, survey exhibition of his work at the Canberra School of Art Gallery in May 2001. His most recent group involvement was with the National Sculpture Prize and Exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, from which a work was acquired for the collection: a punching bag provocatively cased with leadlight glass. His public art commissions include Flood Plane, an 83-metre farm irrigator with neon text, on a lake (Canberra 1990), Transmission Tower (Adelaide 1992), The Fourth Pillar (ACT Magistrates Court 1997), Ruach (Cabrini Hospital, Melbourne, 1998, with David Wright), House Proud (Canberra Playhouse Theatre, 1998) and he was working on a commission for St Vincent's Hospital in Sydney for 2002. He was the recipient of a number of grants and awards, including Australia Council residencies in New York (1989) and Manila (1991), the inaugural ACT Creative Arts Fellowship for Visual Arts in 1995 and the Canberra Arts Patrons Organisation Fellowship in 2000.

In 1993, I find, Neil Roberts quoted Julian Barnes, from his History of the world in 12 chapters, at a forum in Adelaide: 'Is love what will survive us? It would be nice to think so. It would be comforting if love were an energy source which continued to glow after our deaths.' After comparing this idea to his childhood fascination with the diminishing spot of light on the television screen after the set had been turned off, he then recalled Barnes's story of a man who was remembered not because of 'his passions, his love or his bonds, but because in 1830, he was the first person to be killed by a steam train.'

What an extraordinary and painful irony. In contrast, there is absolutely no doubt that our friend and colleague, the gentle and special Neil Roberts, will be very much remembered, through his work and through the way he lived his life, for those very things: his passions, his love and his bonds to the important poetic and physical elements that link people together.