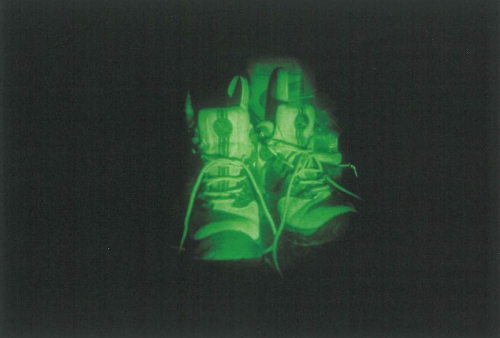

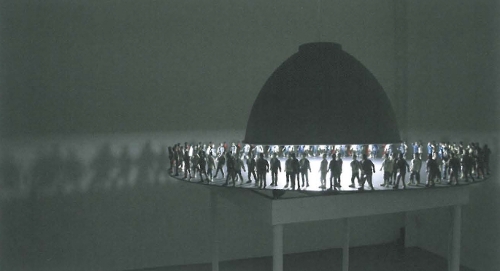

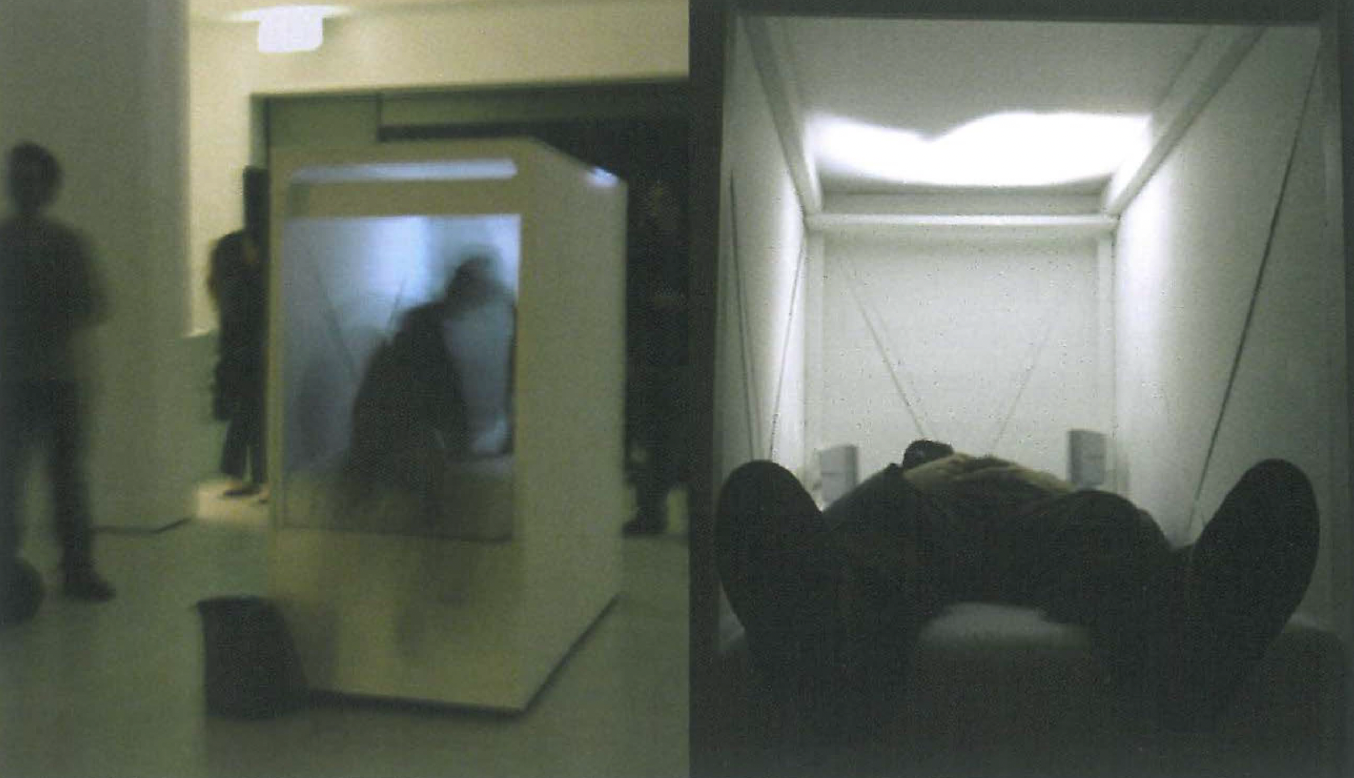

Adam Costenoble's The Chamber is a work that can only be entered alone. It is a plainly constructed rectangular box, as long and wide as the average gallery-goer. Its interior design consists of a looped fifteen-minute screen projection on the inner ceiling, a dark soundscape played through two small speakers beside the viewer's head, and a mattress.

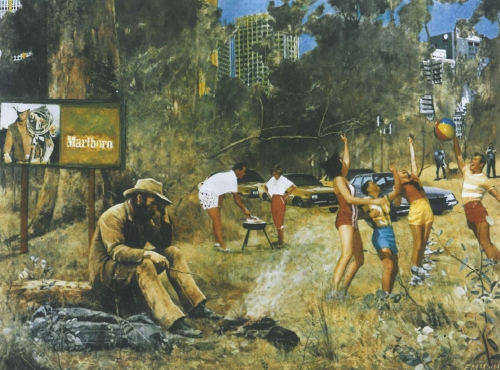

Costenoble regularly suffers the accusation of being an existentialist. From his early days as a painter he cultivated a fondness for the apocalyptic, which has become a common theme throughout his practice. His work has since evolved through screen-based video works into a series of ambitious installations concerned with experience and the tactile. Costenoble's honours project The Mountain – an impressive, hollow, grassy construction – is an example of these works. The Chamber, recently exhibited at Sydney's audio-visual gallery Pelt, is the latest instalment in this lineage of works that address the tensions between art and 'real' experience.

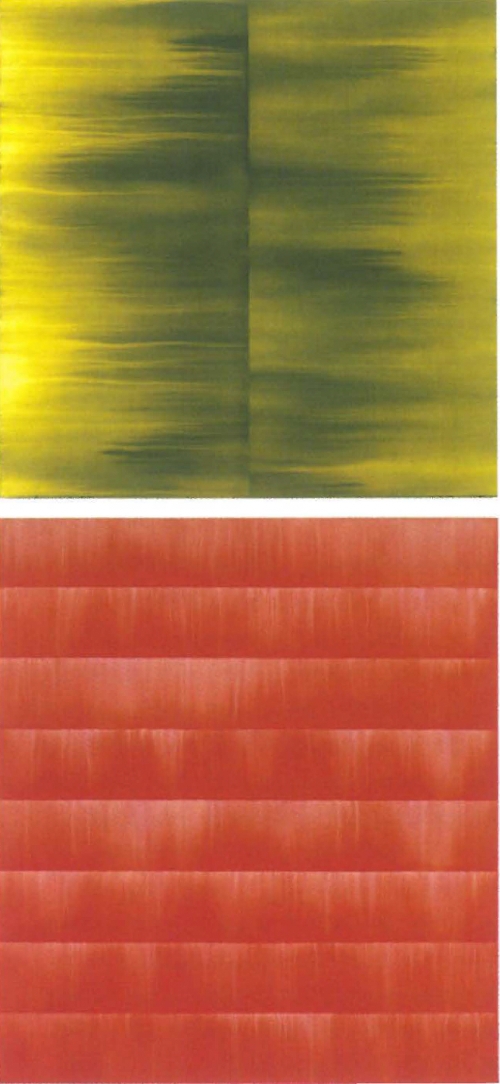

Lying down in The Chamber, I felt immobilised and yet was forced simultaneously to wander, without intention, through a dream-like landscape of visual ambiguity, heightened by a foreboding soundtrack. On one hand The Chamber places the viewer in an inherently receptive, restful position, wrapping itself around the subject rendered introspective, capturing it in an ideal state to absorb stimuli. On the other hand, the work's menacing overtones provoke a heightened bodily response. Overwhelmed, I fell completely and uneasily into the world of the work and yet this sense of unease, generated by the darkness of the sounds and images, kept me acutely aware of my body and thus also of the work.

Despite this rift, the work still feels like the experience of a 'whole', in the sense that artwork and response become somewhat indistinguishable. It would be easy to compare it to other immersive screen works. However, immersion refers to a strategically seductive or aggressive relation to the viewer which is not shared by Costenoble's work. The Chamber's capacity to generate a momentary inversion or conflation of the senses separates it from other screen-based works similarly concerned with generating an affective or bodily experience.

In this way, it is a contradictory space, where the disjunction in the viewer's experience is amplified by the distortion of sounds and images. But through this distortion a sort of equilibrium is achieved. Audio and visuals work hard to compensate for what the other withholds in its abstracted form. The result is a confused perception of a constructed reality.

Costenoble's approach is characterised by a challenge to the conventional distance between viewer and art object. For example, he strives to abandon the division between 'listening' and 'watching', and in its stead awakens an experiential understanding of perception in the phenomenological sense. Furthermore, the disappearance of the distance between viewer and artwork indicates the disappearance of both terms. That is, the viewer becomes a participant and the artwork - a new 'real' space to be experienced in and of itself.

Rather than being an immersive artwork predicated on a distance between viewer and work that cannot be overcome, The Chamber is designed to meet the participant at the level of experience. However, this loosely unified experience is continually undone by the subject's inevitable oscillation between a straightforward experience of immersion and a physical awareness of context.

Facing the dilemma of trying to make art that isn't art is a recurring theme for Adam Costenoble. The Mountain, a work recently exhibited at Sydney's Artspace, shares this problem. Wanting viewers to immerse themselves in the 'real', Costenoble envisaged a work that could be accessed at a purely physical level, without the distractions of sign and metaphor. The result was a large turf-covered mountain that could be experienced from inside and out. Though aesthetically and affectively successful, the fact remains that it wasn't a real mountain. Yet the experience, the dampness of the air and smell of wet earth from inside it, was indisputably real. The Chamber uses virtual media to generate an actual experience of a new 'real' space, For it is both a 'real' experience of a 'false' space, and a 'false' experience of a 'real' space.

In his habit of making works as technologies of the 'experiential', Costenoble has mastered the critical tension between the actual and virtual. And as such, this work grapples productively with questions of affect, bodily experience and perception in relation to screen-based art.