Given the philosophical nature of Clearing, I was initially tempted to submit an appraisal with only two words – The Review. A term used by German philosopher Martin Heidegger to describe the event that must take place in order to see the inherent 'truth' of an object, clearing is the mindful process of eliminating symbolic meaning. Once free of all cultural meaning and significance, the world and how one perceives it is cleared of excess baggage and existence can be viewed in all its unattached glory. Objectified mystery in its purest form, unsoiled by the grubby fingerprints of artsy musings, intellectualisms and personal experience, clearing unearths the enigma.

Applying the same logic in the art gallery was the prime motivation behind curator Colin Langridge's selection process for works to include in the culturally challenged Clearing. Works that eluded recognition in any human sense were prime bait for Langridge's explorative philosophical foray into providing a contemporary standpoint for Heidegger's theory. Presented in the polished confines of the CAST Gallery in Hobart, Clearing showcased the work of five emerging artists working primarily in the field of sculpture.

Tucked snugly into a corner of the gallery were an ethereal collection of salt encrusted organza trinkets. Similar in size and shape to the frosted blown glass of antique perfume bottles and porcelain eggcups (there goes my cultural baggage), Rosemary O'Rourke's recent work exuded the essence of familiarity yet hinted at possibility with the faint breath of what might have been. Intricately hand sewn into doll sized, impossibly delicate objects of a softly feminine design, O'Rourke's Untitled, 2002 series whispered the sweet poetry of mysterious beginnings.

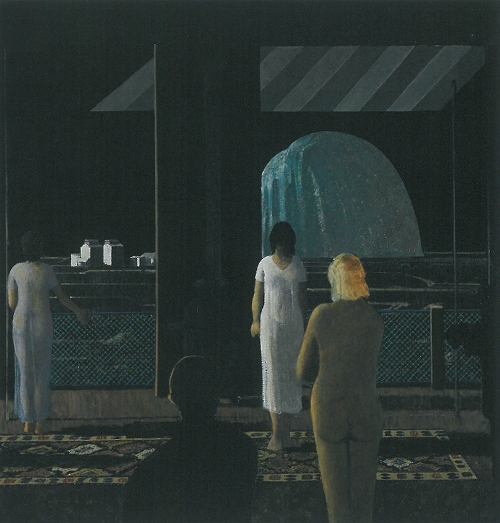

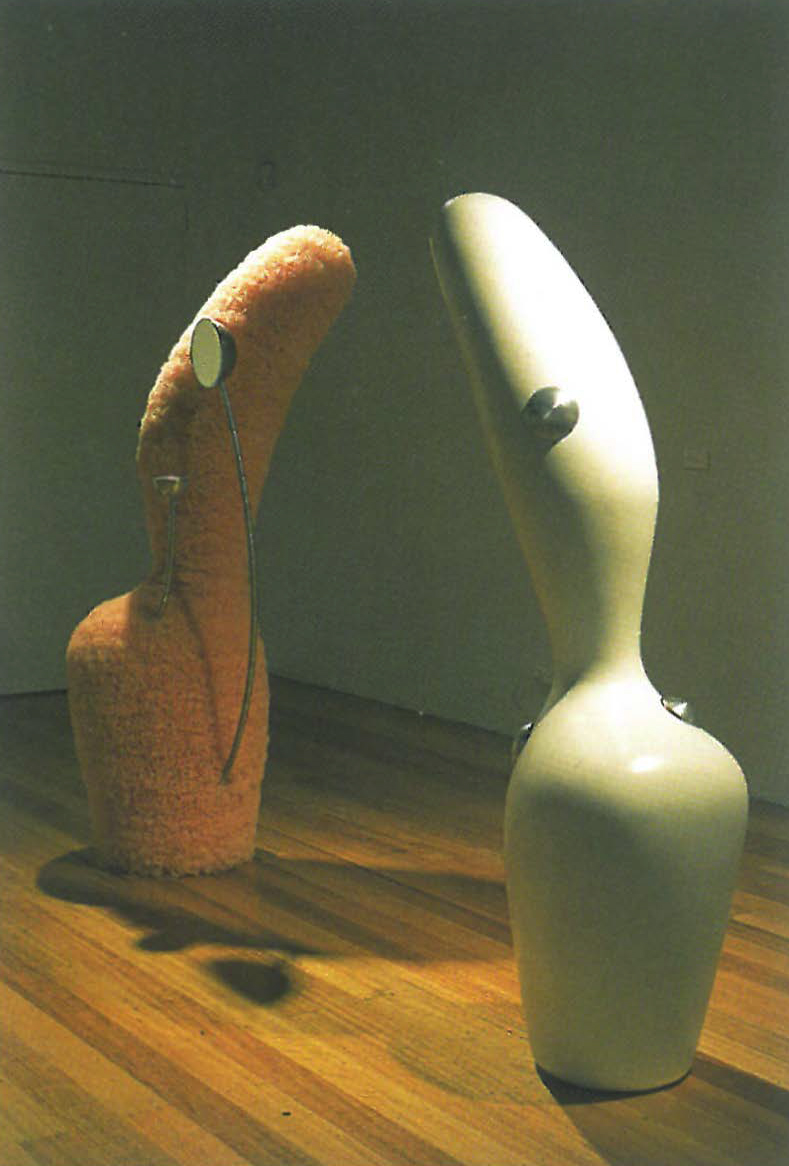

Poised confidently opposite O'Rourke's work were Anke Kindle's outrageously precocious sculptural siblings Precious March, 2001 and Tulled Lena, 2001. The most successful contribution to Clearing, Kindle's sexy fibreglass globsters defied classification with overzealous eccentricity. The slick white surface of the voluptuous five foot Precious March was lusciously offset by the stiff pink frills of nylon netting that covered the surface of Tulled Lena. Large steel buttons, armlike metal protrusions and an eye-level circular mirror served as carefully placed appendages on the enticingly strange dollops of a Barbarella-like fantasy.

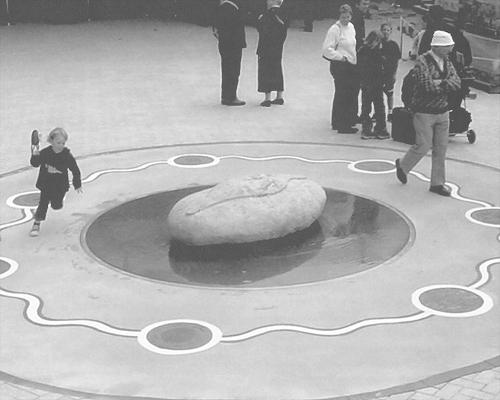

Spilling out into the courtyard of the gallery was Ben Booth's metallic Vessel, 2002. Twisting and turning into a room-sized skeletal structure, Vessel seemed to mark the languid remains of an unidentified mechanical creature. A stark contrast to Booth's chunky wooden configurations (Navel, 2002 and Benefit, 2002) held inside the gallery, Vessel loomed with graceful simplicity.

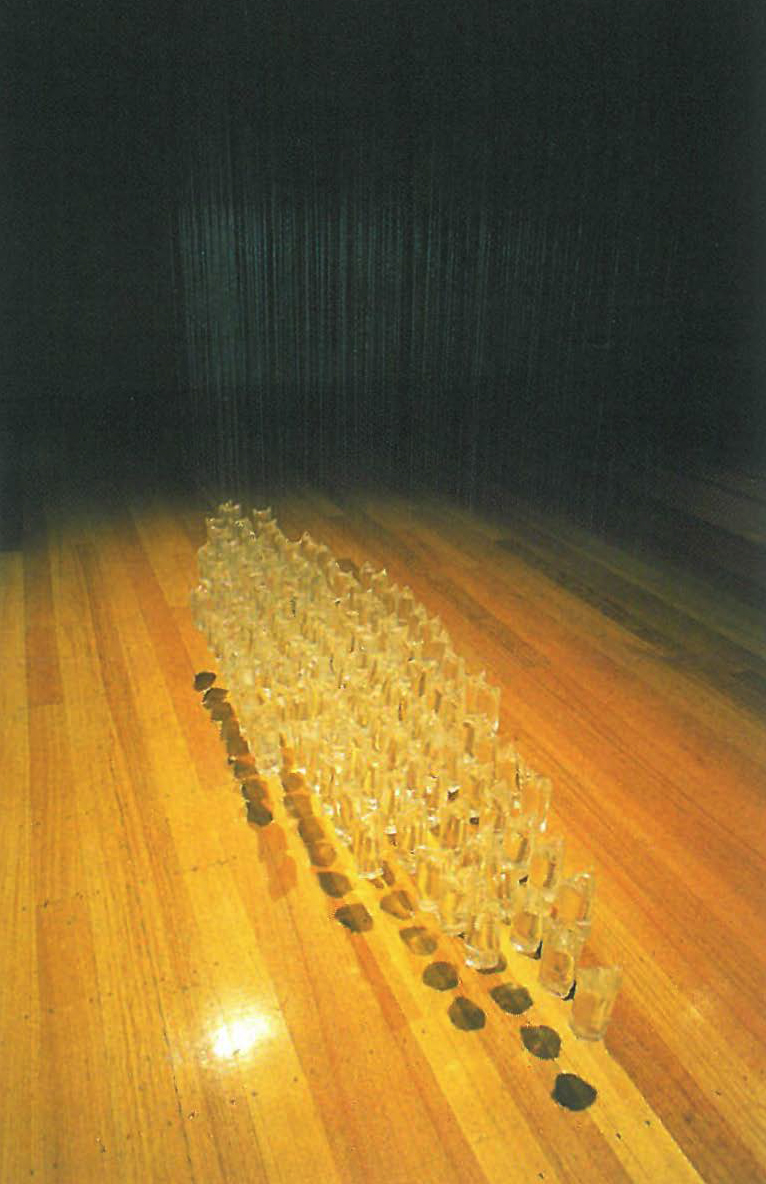

Hovering in a tight cluster a palm's length above the floor were the compact water-filled clear plastic bags of Trudi Brinckman's Current, 2002. Suspended from the ceiling in a tense formation, the tiny pillow-like bags strained against gravity and relinquished the freedom of fluidity to the confinement of plastic. Like the central workings of a water catchment project, Brinckman's Current balanced on the edge of recognition in a trance of crystalline beauty.

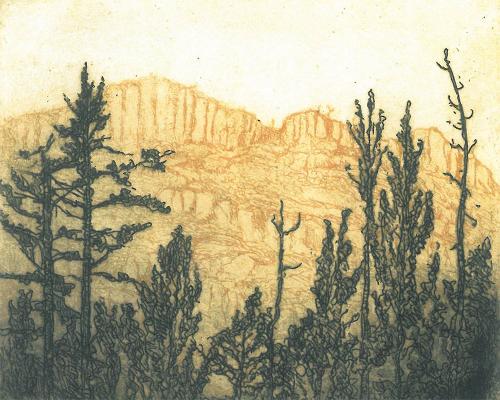

Nine panels of thick black photographic paper embellished with random milky bronze distortions created the blurry dappled surfaces of Kim Portlock's From the Lure 1 and 2, 2002. Vaguely resembling an oozing organic form, the seeping patterns of Portlock's images were like dense reflections of the multi-layered surface of a bizarre supine chrysalis. The unbearable strangeness of being captured on film.

To let an object in an art gallery simply 'be' was a harder task than initially imagined. Human evolution from Neanderthal to an upright being of emotional complexity has nurtured an innate ability to question, to seek out an answer or solution to anything that perplexes. For thousands of years we have sought the meaning of life and traversed far corners of the earth with the same kind of insatiable appetite that now allows us to penetrate the deeper realms of space and technology. Almost every rock remains unturned. It is small wonder that anything inside the artspace entices immediate deconstruction. Although I like my art with a few grubby fingerprints of self-evaluation, Langridge's ambitious exhibition coaxed the viewer to hold back assumption and truly 'see' what lay before them. To see the essence, to leave the rocks unturned. In a world occupied by many determined to strip every cell of its underlying mystery, an object that can solicit the opposite and retain the enigma must surely border on the sacred.