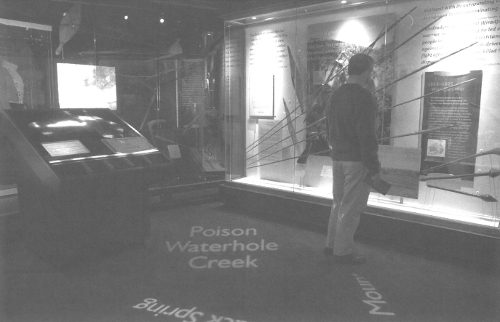

Recently I overheard two conversations where the old 'Is it art and does it belong in an art gallery?' question was being given a good airing. The exhibitions under discussion were Reporting the World: John Pilger's Great Eyewitness Photographers, his selection of documentary photographs and African Marketplace curated by David McNeill and Jill Bennett, an eclectic mix of syncretic objects including: shop front advertising, textiles, sporting paraphernalia, contemporary paintings and a cheeky plastic chicken. These exhibitions do undermine conventional preconceptions about what is art, but they also share a more interesting and fundamental ideological concern. Both are critical examinations of the effects of globalisation. Although they are discussing the same topic, each exhibition deliberately tells a very different story.

In his introduction to the publication of the same name (21 Publishing London 2001)John Pilger openly acknowledges that in Reporting the World he is constructing a narrative. He casts the photographer heroes as 'both storytellers and truth-tellers'. John Pilger is an outspoken journalist, well known for stories exposing his own 'axis of evil', a gang of villains that includes the IMF, The World Bank and globalisation. His indictment of globalisation is neatly encapsulated in a cold war photograph taken in 1969 by John Garret which shows a Coca Cola van in front of the Berlin Wall. It can also be seen in images by the same photographer of deserted docks in 1990s Britain, where abandoned cranes loom, lamenting the loss of skilled jobs in the first world as well as the exploitation of labour in the third.

It comes as no surprise that in Reporting the World citizens of the first world, Americans, British and white South Africans, are shown almost exclusively as racists, vigilantes and poor white trash. Australians are portrayed in much the same way, although placement in a room with Africa, Indonesia and Bangladesh may indicate that Pilger sees Australia's first world status as marginal. Barring a few photographs of brave, if futile resistance, the citizens of the third world are portrayed as victims. They are victims of Western-backed wars and fascist regimes, global economic forces, floods, famine, rape and torture.

Most of the images in Reporting the World are graphic depictions of horrific events. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, the exhibition has been enormously popular. What are we seeking through this mass public exposure to the trauma of others? Are we looking for some kind of catharsis or absolution? It is unclear how we are supposed to react. Is John Pilger teaching or preaching? Either way the story he is telling in Reporting the World is unrelentingly grim.

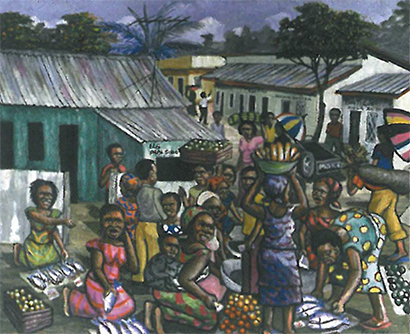

African Marketplace tells a different story. This exhibition stresses the dialectical nature of globalisation. It is about transformation, narrative multiplicity and the reciprocal flow of information. In the African Marketplace culture clash is a catalyst for the creation of vibrant hybrid art forms.

The exhibition includes baskets woven from telephone wire which find international markets, miner's helmets that mutate into anthropomorphic head dresses for soccer fans, lengths of fabric that warn of the danger of land mines and shop-front advertising that both contradicts and embraces Western influence. In one such advertisement a wall-eyed dentist grasps a bloody tooth in a pair of pincers. He wears the white Western dental smock and proudly declares that his diploma is from Paris, yet one of his post-operative patients wanders nude through the surgery while his current patient looks visibly distressed and literally sees stars. This doctor may be practising Western dentistry, but his advertisement negates Western portrayals of medicine as sane, painless and sterile.

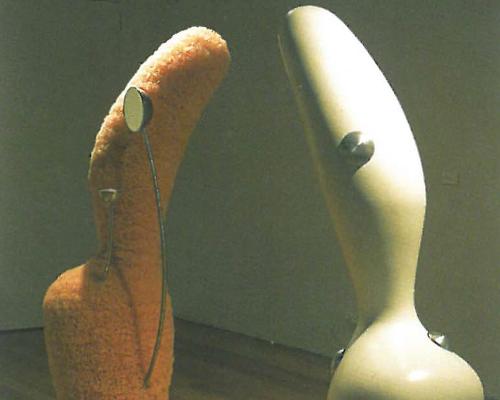

African Marketplace challenges accepted notions about Africa and African art. Perhaps the most unexpected selection in the exhibition is not the coffin shaped like a lion but the work of a celebrated art star, South African William Kentridge. This artist may be white but he asserts his right to claim an African-ness, challenging our preconceptions of Africa as black, third world, authentic and primitive. Meshac Gaba's Untitled pieces (from the Museum of Contemporary African Art Project) are equally confrontational. One is a compact mound of shredded bank notes, the other is paper towels printed with images from TV or newspaper news. These images depict guns, food, money, soldiers and people all over the world with their arms raised in protest. Gaba's work lacks any trace of tribal or 'authentic' Africa. This is not the work of someone trapped in any kind of darkness, let alone a dark continent; this artist is fully illuminated by the glare of the global media.

While Reporting the World places globalisation firmly in the role of villain, African Marketplace tells a story without villains or victims, where cultural interaction is dynamic, and resistance is possible through both absorption and transformation.