Mr Rupert Myer has earned the respect and gratitude of the visual arts and crafts sector for confirming, in a well-conducted review, that the visual arts in this country are significantly undervalued and underfunded.

The Myer Inquiry was set up to evaluate the visual arts and crafts in relation to the society at large and how the economics of this sector function in relation to other sectors. It has produced a snapshot of where we are now – how many people use the sector, how much money is generated, how much money is spent and the roll-on effect on the GDP. Its findings are, roughly, that the sector is energetic, enterprising and forward-looking, that it does wonders with very few resources, but that the talent, energy and potential of its people and institutions are being diminished by a slow process of attrition in which funding has remained static or has gone backwards and conditions for a healthy creative culture have deteriorated for lack of government nurturing.

It was not the brief of the Inquiry to look back, but it does cause us to reflect on how much things have changed in the last thirty years. Back in 1972 there were artists (mostly painters), a state-run art museum in all but one capital city (Brisbane) and a handful of feisty commercial galleries. There were art schools, there was art history, there was craft, there was sculpture and there were public monuments. There were a number of council-run museums of art & craft in regional centres mostly sustained by volunteers.

There were no regular arts funding programs, there was no Australia Council for the Arts, there was no National Gallery of Australia or Sydney Biennale, and the Adelaide Festival was in its infancy. There was one real art magazine and virtually no books on contemporary home-grown visual arts. Australian art was unknown overseas apart from the odd show in a London gallery. Indigenous art was not considered art. Women artists were ignored. Digital art was just an idea in the minds of a few computer buffs.

The evolution in three decades of the arts sector echoes that of other sectors in Australia – academic, scientific, and commercial. As a new culture in an old world in which increased travel revealed the unfavourable contrast between how the arts were valued in other countries and our own, the emulation factor took over and we entered a catch-up phase. This was the decade of the lone voices, the pioneers, the self-motivated people with a mission. By the end of the seventies the heroic figures were joined by other battlers equally determined to make a difference and gradually the arts sector as we know it today was formed.

Compared with 30 years ago, the infrastructure now is not only substantial, but has spread into nooks and crannies of society culturally as well as geographically. What was sketched out in the seventies started to take form in the eighties and became a workable structure in the nineties. By the turn of the century the structure was a container for not only those of the pioneers who had not burnt out, but thousands of new recruits – artists, curators, writers, administrators, lobbyists, philanthropists, art dealers as well as people in the related government and commercial sectors. More and more people were taking part in the arts, as artists and craftspeople, as students and scholars, as administrators and entrepreneurs; more and more of the public were going to galleries and museums, buying art, attending lectures and special events, and wanting better documentation about it to take home.

Around 2000 it began to dawn on artists and their support teams that they were no longer merely tolerated as colourful but misguided appendages to the proper condition of society but were actually beginning to be recognised as performing an important role – that of holding together the fabric of cultures and helping define what it is to be human and alive today. Why then were most of them struggling to make a living, with average incomes of $15,000? Why did their friends who worked with them to create the exhibitions and look after the collections work extraordinary hours for salaries way below those of their colleagues in other sectors? How had they arrived at this point?

The answer is that the catch-up which started in the seventies as Australians compared their arts sector with what they saw in Europe and America could only have achieved the results it did in so short a time by ignoring these issues and ploughing on regardless. The culture of personal sacrifice for the greater good was inherited by the new recruits to the contemporary art centres and regional galleries, to every branch of the arts except perhaps those protected by the Public Service, so that to expect a decent reward for a day's work seemed simply a pipe-dream.

We seem to have reached a watershed moment in the history of the arts in this society. As other sectors – primary production, manufacturing, services – decline in the national psyche and we search for other ways to evaluate labour and the worth of the individual, the arts have emerged as a source of understanding and communication in ways which were not recognised as recently as 30 years ago. It was this realisation, coupled with an increasing sense of frustration at the way the gains of the last 30 years were being eroded by an era of static funding to organizations, the decline of the effectiveness of the Australia Council and the downgrading of the earlier hard-won principles (such as mandated fees to arts workers on funded projects), which gave courage to the National Association for the Visual Arts last year to press the government for a thoroughgoing review of the visual arts and crafts sector.

The results of the Inquiry, delivered on 6 September 2002, are gratifying. Mr Rupert Myer and his team found not only that most institutions are so critically underfunded so that they can only realise their most basic goals, but also that funds allocated for individuals, whether artists, curators, writers or others, are inadequate to the task.

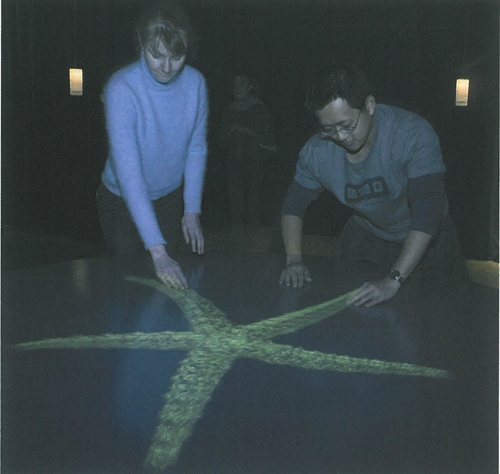

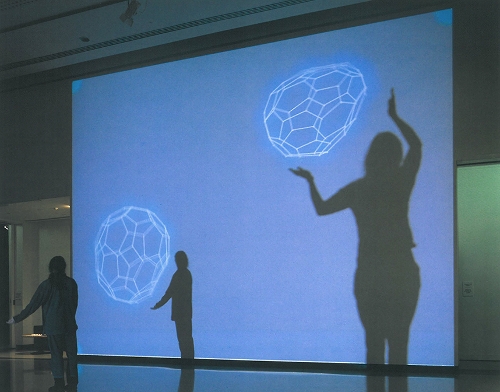

He has recommended increasing the total amount allocated by state and federal bodies by almost a third, from around $38m to $53m per annum. The Myer Report is not just about funding dollars however. It also addresses indirect ways of increasing income to arts workers, ranging from modifications to Social Security arrangements and income tax thresholds to introduction of a resale royalty scheme ('droit de suite') and increasing tax incentives to encourage philanthropy and donations. The Report has sensible things to say about and recommendations to improve conditions for indigenous art, new media art (a new technology loans scheme) artist-run initiatives, moral rights, copyright, international promotion, publishing, touring exhibitions and major events to name a few.

The implementation of the recommendations has been designed on a 'leverage' model by which the Commonwealth would provide a core $7m p.a. plus an extra $6m p.a. contingent upon the states and territories jointly contributing $2m p.a. This is the normal model for such Reports to the Commonwealth, but with the full set of states and territories being of the opposite political persuasion to that of the feds, there may be potential for some resistance on the part of some arts ministers to endorse and act upon it decisively. The next few months will be crucial in the run up to next year's Federal budget and advocacy bodies will be working overtime to make sure that state and federal politicians are left in no doubt about the need for the recommendations to be endorsed and the funds to be earmarked. Petitions to state and federal ministers are being circulated by NAVA through galleries, arts centres and art schools and it is important that as many people in the sector as possible add their names to these.

Two things are very clear: the Myer Report has the full support of all the peak bodies in the visual arts and crafts nationally, and it is a once in a generation opportunity to give the visual arts and crafts the recognition they deserve. Boot-strapping is not an option any more for professionals who both know their own worth and have other options overseas or in other industries. Space must be made for a new tier of workers who will take over when the older generation retires without waiting for them to fall over. An arts sector where energetic thirty-something PhDs are working nights in call centres to pay the mortgage is no longer sustainable.