Wide Open was intended as an antidote to the dominant narrative of self-congratulatory federation-inspired nationalist, or even jingoistic, exhibitions created for the centenary of federation. The problem for a curatorial concept like this is that subsequent art tends to come from that radical, questioning position anyway. A great deal of modernist painting in Australia was in fierce reaction to the certainty, sentimentality and superficiality of mainstream readings of Heidelberg and later landscape painting. Without a more focussed curatorial intention this show has become a mere catalogue of Australian art history constructed from available works, a list of things artists did and of individual artists' taste, visual style and intellectual and expressive pre-occupations in the century that followed federation.

Constructed largely from the UWA collection and augmented with works from both other collections and artists, this exhibition is disappointing in several ways. For example, it is always good to see one of the early Nolans that were so familiar around the university in the 1960s. It is entirely relevant in this context and they are beautiful things, but it is a bit like hearing a Beethoven symphony: you can't do it too often if you really want to connect. It needs a bit of space. Here it is on a crowded wall in a sequence that gives no room for any work to breathe and reduces everything to its cliched, art historical lowest common denominator. Beside it a passionate, intense Tucker becomes merely petulant and a bit grumpily banal. It is certainly a case where less would have been more.

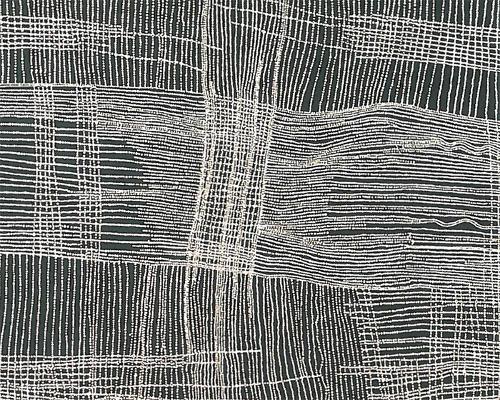

The early West Australian works similarly are not shown to advantage. If the intention is to make us connect John Campbell's genteel 1904 watercolour of the Swan Brewery with the radical Aboriginal politics that frame that building today, then that message needs to be made clearly readable within the experience of the exhibition. Several Aboriginal works are included but they are marginalised by being made to represent overtly alternative positions and belittled by a sort of political correctness. If a more radical, ironic reading of our culture is the aim then these issues are central.

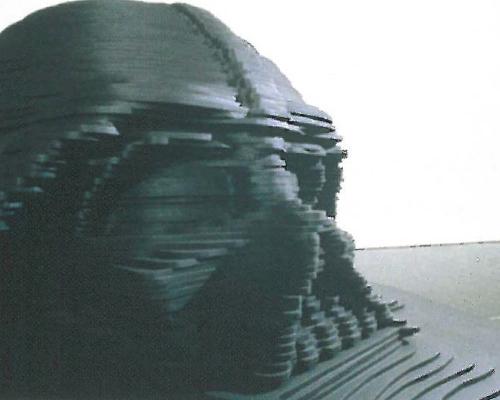

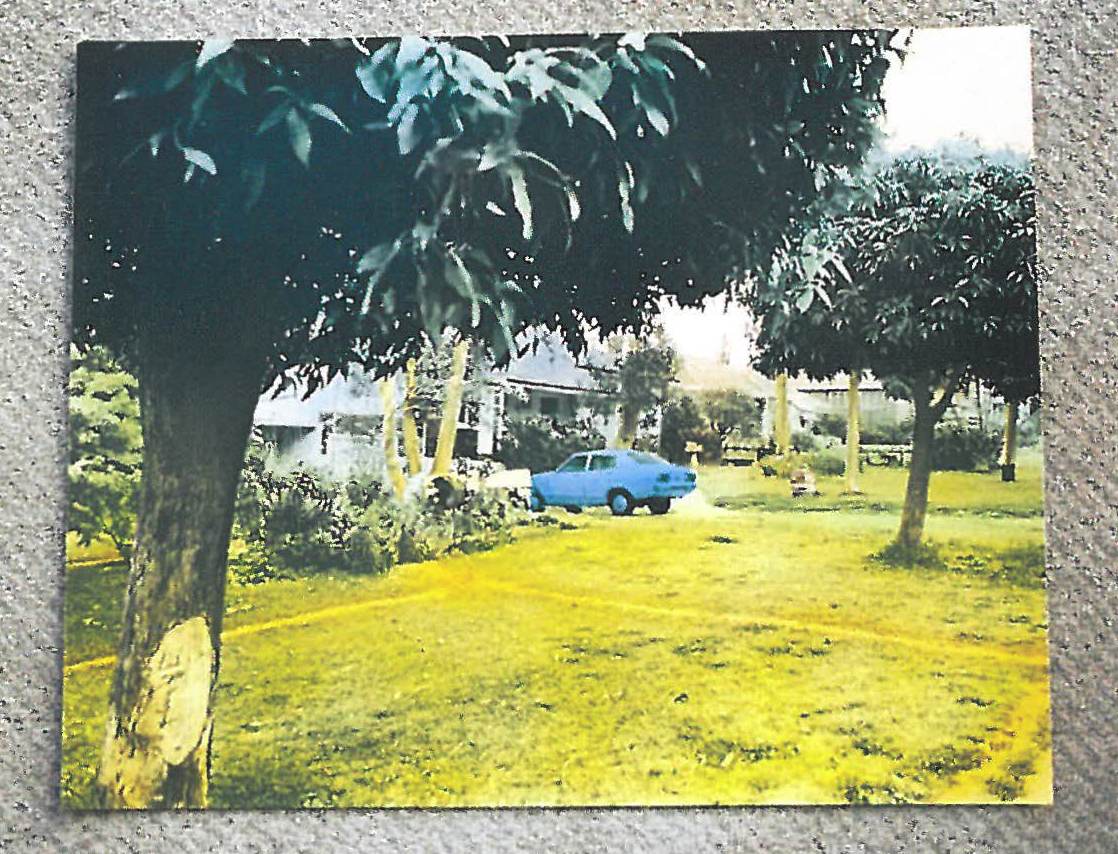

However there are some very good things to see in this exhibition, most particularly Tom Gibbons' 1982 set of eight hand-coloured photographic landscapes. These airbrushed black and white bromides are titled Random Landscapes. Yet they are anything but unplanned. Himself then a member of the English Department at UWA, Gibbons had a member of the Geography Department select thirty sites in the Perth metropolitan area from a numerical database. A coin was tossed to determine the direction of the camera at the site. Gibbons saw this as a way of negating the inevitable picturesque urge. Here any scenic pretensions are made redundant by straggly chicken wire fences and the crazy perspective of road verge engineering. Garish blue skies and schmaltzy pink sunsets preside over concrete curbing, bitumen dead-ends, sandy perimeters and degraded patches of scrub.

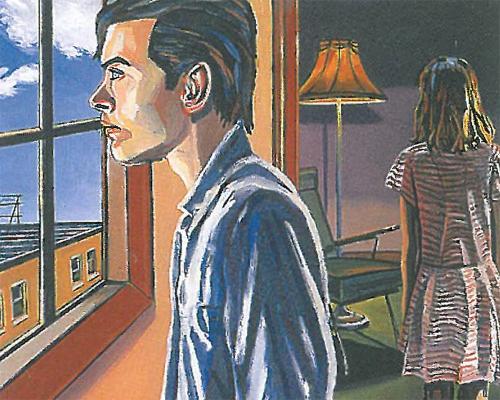

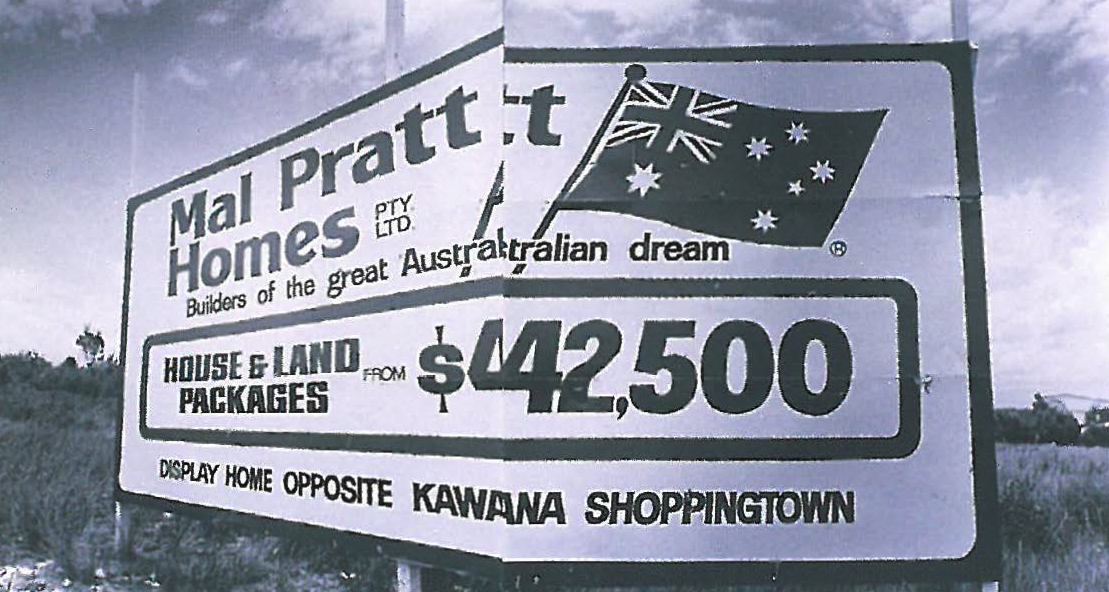

In Grant Taylor's two photomontages, young men in suits video kangaroos on a wasteland awaiting development. In a macabre fantasy in the corner a tiny, grey suited youth clambers up the gigantic form of a monster marsupial. In Suburban Simulacrum young parents compulsively video the archetypal toddler on a desert of lawn amid the disfiguring shadows of camcorders, perpetually distancing and falsifying experience rather than participating directly.

Andrew Smith's nocturnal tourism in a fading country town provides a good antidote to the usual sunny cliches. His set of four cibachrome prints of artificially illuminated shopfronts photographed at night are like small stages for a drama, abandoned movie sets or perhaps a forensic archive of forgotten and disregarded treasures fast disappearing without us noticing.

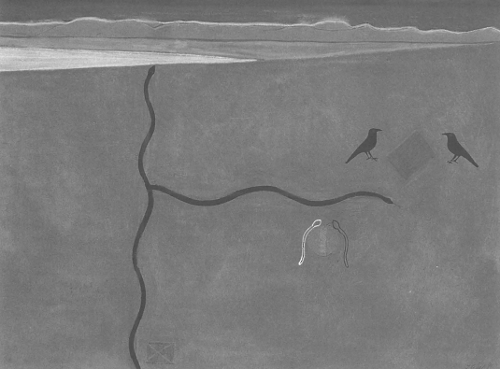

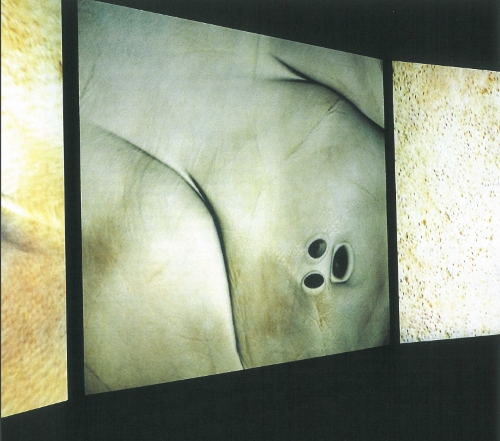

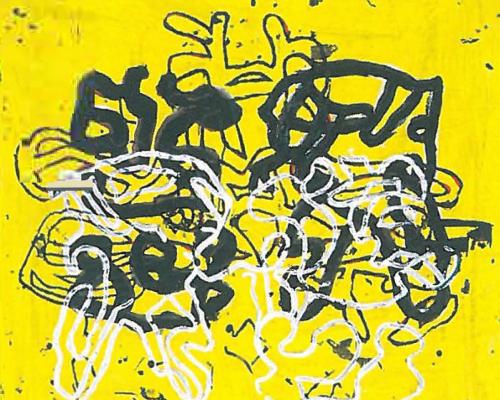

Tom Alberts' dead fawn lies sprawled beside a crashed car. Jo Darbyshire claims a tougher feminist analogy with the land than the old, soft, body curves story, in her Wildflowers. She inverts the Australian myth of male supremacy in the bush, her rampant girls rampaging on a zipped up tent flap leaving no doubt that it's Mother earth. Stuart McFarlane's familiar brew of careless violence and predatory sexual arrogance has a local ambience looking down on the Narrows Bridge from a city high-rise. Valerie Tring's image of Blue Waters, a house which became a local icon of both modernity and Italianate design of the fifties, is lost in a carpet-like sea of abstraction.

Christopher Pease's preserved python in a bottle on a museum stand comfortably distances the city dweller from any fears of inadvertent contact with dangerous wildlife, as Commissioner Neville protected the white community from its darkest fears of contact with Aboriginal society.

This could have been a much better exhibition. It is a perfect illustration that an exhibition is itself a sort of artwork that requires both intellectual rigour and visual sensitivity and coherence. An exhibition creates a context in which certain ideas emerge and can be assimilated. Most artworks look a whole lot better and their meaning is illuminated and becomes accessible in a relevant, positive context.