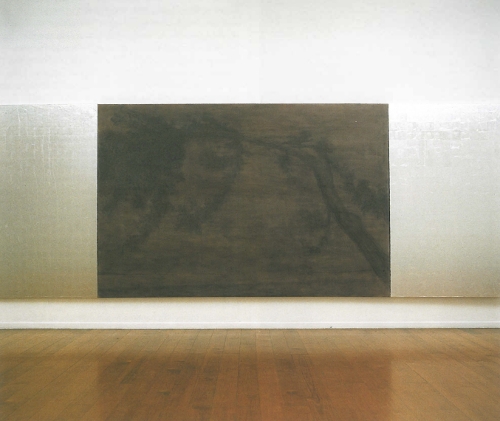

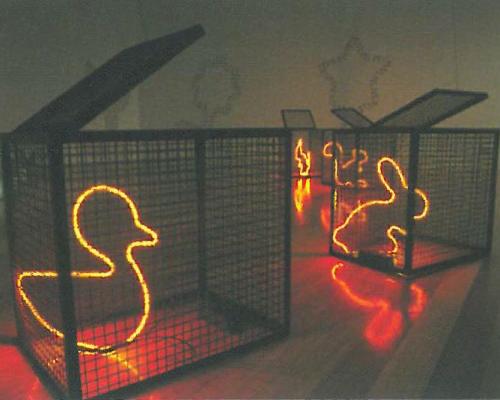

green line by Alice Springs-based artist Pip McManus, could hardly be more keenly relevant to the moment, touching specifically on issues of migration, Aboriginal dispossession, and the deep-rooted tensions between the world's great monotheistic religions and cultures. More universally, it is about boundaries, the tragedy of being stuck behind them, and the mostly unrealised possibilities of crossing them.

It takes its name from the demarcation line in Jerusalem which separates the Israeli and Arab parts of the city, one of the most fraught demarcations on earth, but, as McManus so poignantly demonstrates, our world is full of them.

Raised in Perth, McManus was first confronted by large-scale dispossession when she travelled in the Middle East after leaving school. The refugee camps she saw in Beirut, that had sprung up after the 1967 Six Day War during which Israel annexed East Jerusalem, have never gone away. She has made several return trips to the Middle East, spending a year in Egypt in 1985.

By this time she was also living in Alice Springs and becoming increasingly aware of dispossession suffered by Indigenous people in Australia. Yet her ceramic work, until quite recently, was light-hearted and decorative. After the Rwandan genocides of 1994, McManus forcefully crossed the boundary between craft and art to evolve a major piece about genocide, The Poisoned Well, first exhibited at the Alice Prize in 1999, and included in the expanded 24 HR Art version of green line.

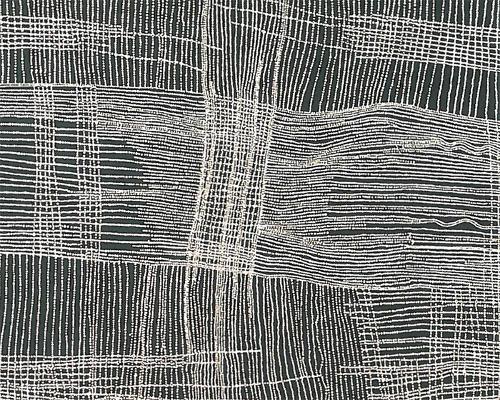

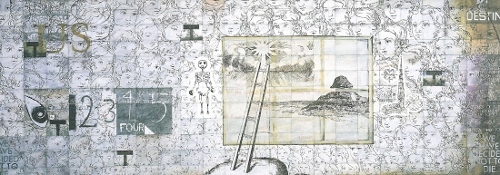

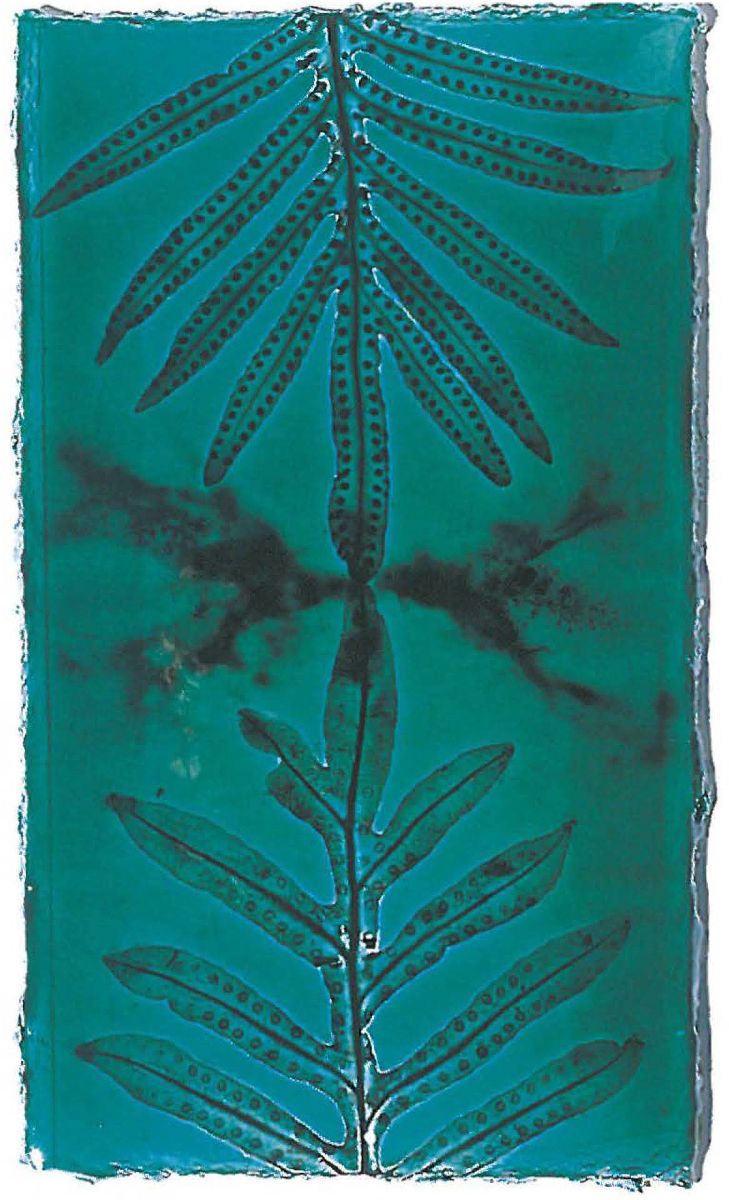

Her starting point was the deep interconnection of the natural world and society, expressed by exquisite plant intaglios incised in clay tablets in the form of a raised hand, evoking captivity, mortality – each plant form finite and isolated in its beauty under the glaze, each representing a chapter in the history of genocides.

In green line, an understated yet mournful piece on the dislocation of the "stolen generations" uses a single raised hand with plant intaglio, from which, suspended on a thin red line (struggle and pain), is a tiny golden bell (church, school and, through them, the state). Above the hand, like the list of names on a soldiers' memorial, is the list of institutions in the Northern Territory where mixed race children removed from their Aboriginal families were placed.

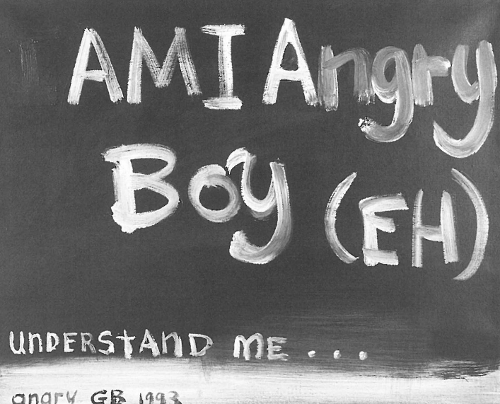

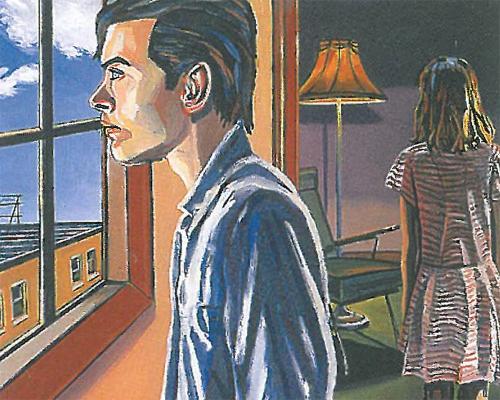

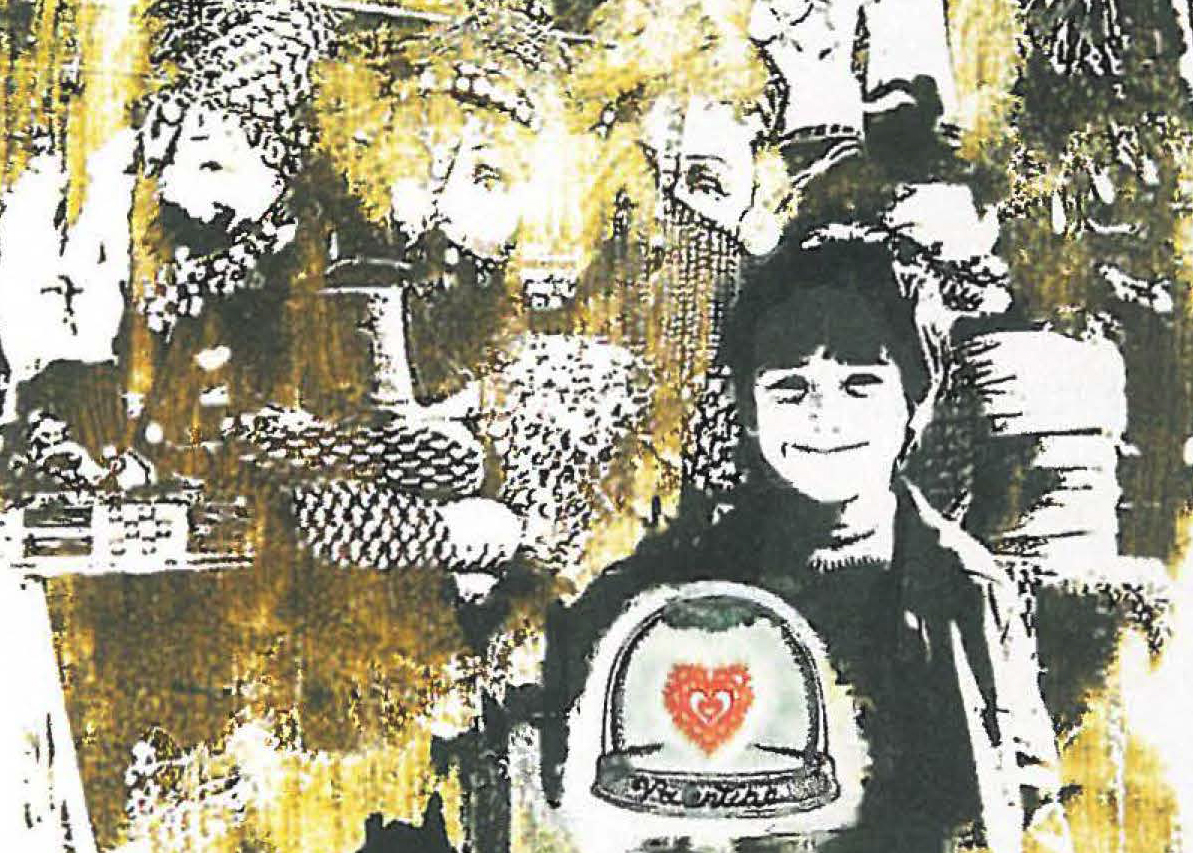

On the other side of the world (and opposite walls of the galleries) another child has his life buffeted by the fallout of ideology and politics. A series of tablets tells the story of Valentine, who in the mid-eighties fled Romania with his family. They waited for 18 months in crowded, chaotic Cairo, surviving on UN rations, until Canberra finally said Australia had no place for them. Eventually Canada proved more generous. The story could equally be told today, perhaps of an Afghani or Iraqi boy. The ironic final image of the series, however, leaves behind asylum seekers to take us to Australian heartland. It shows Aboriginal people sitting under a tree in the Todd River which passes through Alice Springs. Although possibly native title holders, these campers are considered "illegal" and get told to move on.

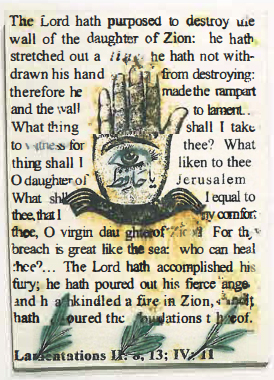

The theme of loss of homeland and the anguish it unleashes is furthered in the show's title piece dealing specifically with Jerusalem, "a golden basin filled with scorpions", as a 10th century Arab geographer, quoted by McManus, described it. McManus again uses the hand icon, this time the "hamsa" seen everywhere in the Middle East, in Jewish and Muslim quarters alike. With its Star of David or its Arab script and magical eye, it stamps religious and cultural identity on the history of the city, Jews and Muslims each having to own their part in the burden of ancient conflict, evoked by McManus in fearful biblical quotations: "The Lord hath accomplished his fury; he hath poured out his fierce anger, and hath kindled a fire in Zion, and it hath devoured the foundations thereof."

Christianity is represented by a fragment of a sixth century mosaic map of Jerusalem, from a Greek Orthodox church in Jordan. McManus stamps it with a single green leaf – a poisonous oleander (perpetuation of old hatreds), yet vulva-like ( life force and renewal), and, with the bleed of its glaze, wound-like (the stigmata – human suffering, sacrifice). Thus, collocated in a place sacred to all of them, Judaism, Islam and Christianity make "the rampart and the wall to lament". And across centuries and oceans, the tiny golden bell rings: "The survival of everyone is related," says McManus, and perhaps never more so than now.