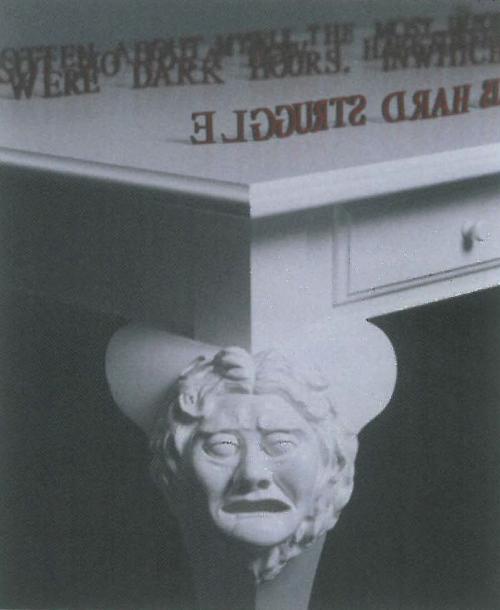

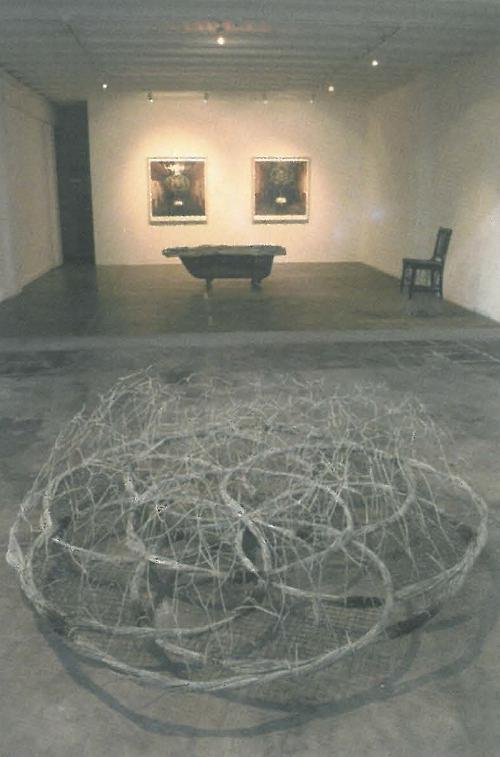

In a remarkable exhibition, curator and visual artist Jo Darbyshire sets out to explode the rules that govern the way words and objects are displayed. The Gay Museum is both a social history of gay and lesbian people in West Australia, and a critique of museum practice. In place of the grinding literalism of the object and its label, we are offered a recoding, or reappropriation of prior meanings. 'Improper' associations abound, as the connotative levels of the object as visual artefact are put in play. It seems that even objects can 'linger' and 'allude' and 'suggest', especially when they get together with a few bad words.

An electric shock machine (1910) sits with a text about changing homosexual orientation through treatment. The remainder of the table case is filled with fragments of used hand soap. The associations of dirt, guilt, the body, and technology collide and linger.

In another case sits a packet of cherry, green, and yellow cupcake papers. They are innocuous, cute. Text on the walls reads: 'Cupcake: an effeminate male, possibly a homosexual (US slang 1900's).' Somewhere else the words 'Lickety Split' rub up against an elegant display of open mussel shells, late 19th century purses, buttons and mink muffs. The aesthetic and linguistic associations of femininity and lesbian erotics are subtle and suggestive.

The intention is not provocation; rather, the exhibition can be seen as response to the effects and implications of the State museums' traditional role as keeper of the past. For if there is no collection of objects pertaining to an area of human history, what are we to say of that history? That it did not exist? What happens to the immaterial, the undocumented, to those histories that have not produced things that fit into Museum Collection policies?

Poofter: Offensive and uniquely Australian in usage & it has been suggested that because homosexuals were supposed to wear cosmetics, the powder-puff, a cosmetic instrument, was shortened to 'puff', which with usage was altered and 'the word became the thing.'

- David Clay, Camping Isn't Gay, 1974, quoted in the catalogue.

'UNNATURAL PASSIONS', read the capitalised letters set behind perspex. I walk the length of the panel and see that the letters are overrun with the 'others' of nature – dirty old dead rats and bats. The panel is beautiful, but why are forks everywhere? Big ones and little ones, fat ones and thin ones. I read on:

Kingdom: Hard Forks

Class: Steel objects

Order: Utensil

Family: Fork

Genus: domestic

Species: metal stemmed

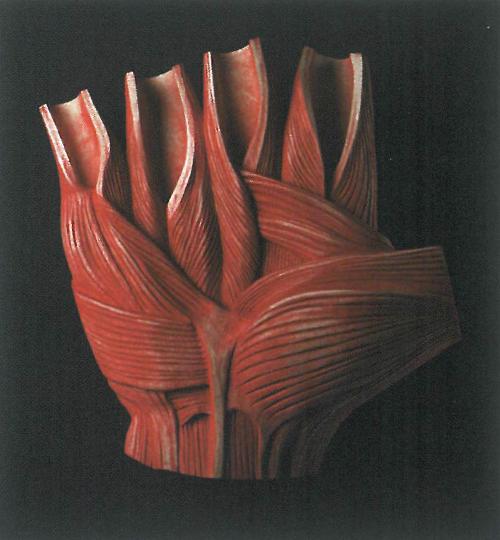

Subspecies: plain round base

Irreverent, poignant and funny, the dynamic of the exhibition lies in its wilful disregard for the 'natural order of things'. More recent struggles around AIDS, gay and women's liberation, share the floor with lists of long-gone gay hotels and clubs, infamous love trysts drawn from newspaper sources, tales of drag, vice, and homosexuality in the Aboriginal community. Squids, mussels, and police truncheons hang out with powder puffs and shame-faced crabs. Somewhere there is a Dawson's Bee, a native of the Kimberley. A gynandromorph, I read, it is 'an abnormal individual combining male and female tissues.'

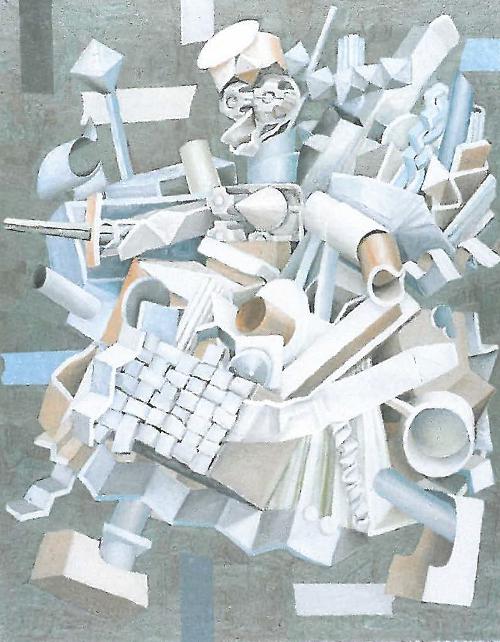

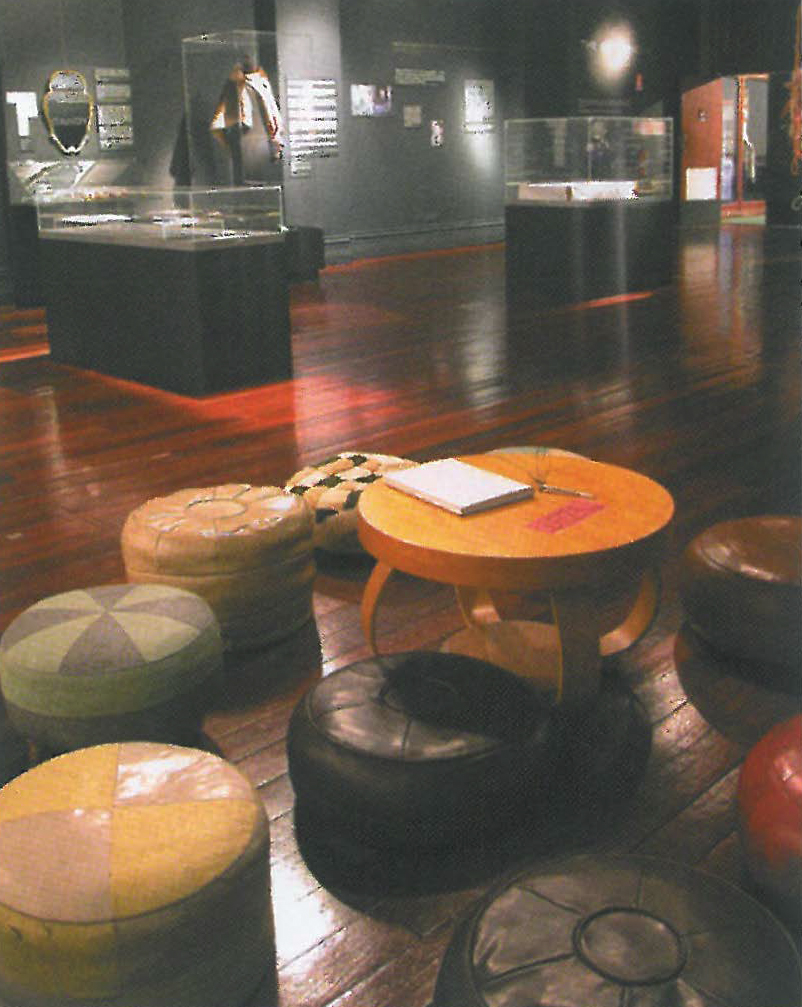

'Unlikely objects, thrown together casually or juxtaposed with text, may evoke new meanings,' writes Jo Darbyshire. When research began on this exhibition, she was told by a collections manager to put forward a thematic and a search would be made of key terms. Implicit in the utopian fantasy of computerised collections is the idea that words can adequately 'stand-in' for objects, and in doing so approximate and exhaust the past, present and future life of the thing. After a poor yield on SEARCH: 'Homosexual, Lesbian, Queer', the curator chose to look at the collections, to see what might be there.

In the historical exhibition, words are to objects as pins are to butterflies (making a mockery of the idea that the very best objects can 'speak for themselves.') Is it possible to release an object and let it mean again? Unhinged from dutiful representation, objects resonate with words in ways far in excess of their obvious functionality or remarkable provenance. This excess is both poignant and powerful: it challenges the dominant models of museum practice by reminding us that things too can partake of 'fugitive communications'. Subjugated groups understand the necessity of saying one thing and meaning another, of the importance of the gesture, the glance. The Gay Museum employs such strategies of indirection to baffle and charm and move us in ways more akin to poetry than public history.