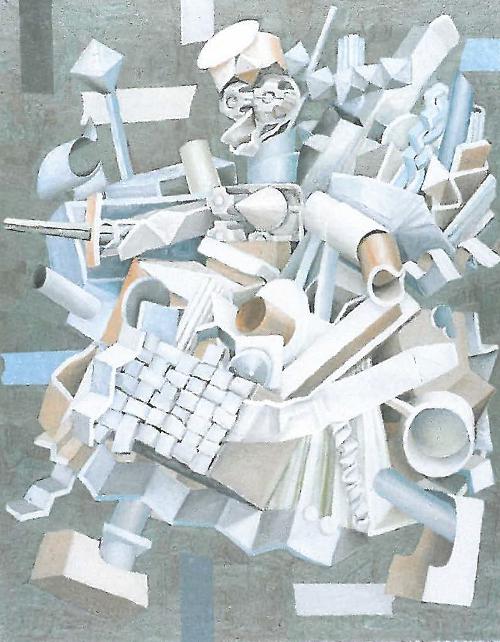

Chris Mulhearn has stated that he likes to 'create friendships between materials' and in a number of respects the sculptural pieces for Fifth Showing at Greenaway Art Gallery represent a fundamental shift from earlier mixed-media assemblages of found objects and materials - a characteristic mélange of corrugated iron, used textiles, timber, car parts and tin. In his latest exhibition, Mulhearn largely confines himself to the use of a single material - manipulating and containing the harsh and ostensibly unpromising strands of galvanised power cable. Interviewed in 1986 by Robert Storr, Louise Bourgeois reflected (in reference to carving) on the lure of a material that is resistant. 'It is a constant source of refusal. You have to win the shape. It is a fight to the finish at every moment. Gaston Bachelard would explain this by saying that the thing that had to be said was so difficult and so painful that you have to hack it out of yourself and so you hack it out of the material, a very, very hard material.' (Parkett Art Magazine, no 9 1986 pp82-5)

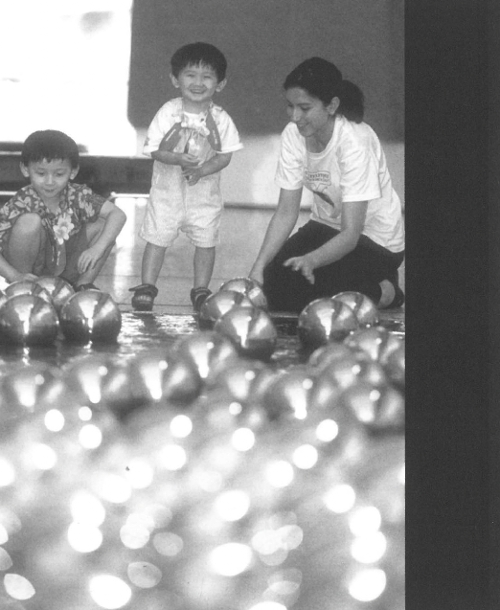

With the five sculptural works of Fifth Showing Mulhearn transcends the difficult physicality of his material, achieving with heliotrope and anabus a lyrical quality, perhaps only present amongst earlier work in Prayer (2001) with its seventeen tall, bowed planks of wall-mounted and weathered timber attached to rusted tin.

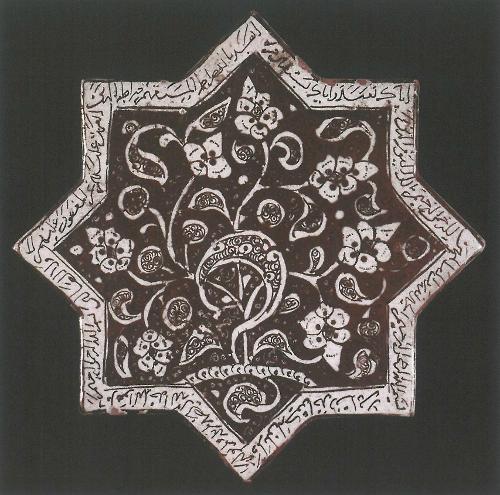

The heliotrope motif lies at the heart of this exhibition and in Mulhearn's pivotal work heliotrope, the looping and woven form of the mandala is both softened and disrupted by a canopy of twisted wire which appears to float above its surface. Belonging to the genus Heliotropium, the blooms of the heliotrope, which rotate to follow the sun, serve as a metaphor for renewal. Typically the work possesses a raw honesty - blackened, welded joints at intervals on the circles of cable are clearly visible, though these in no way detract from the meditative nature of the piece.

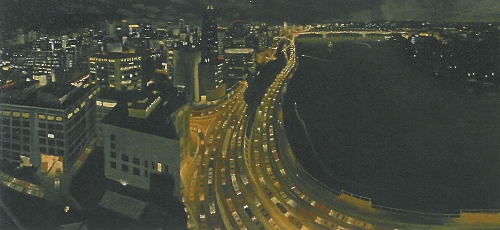

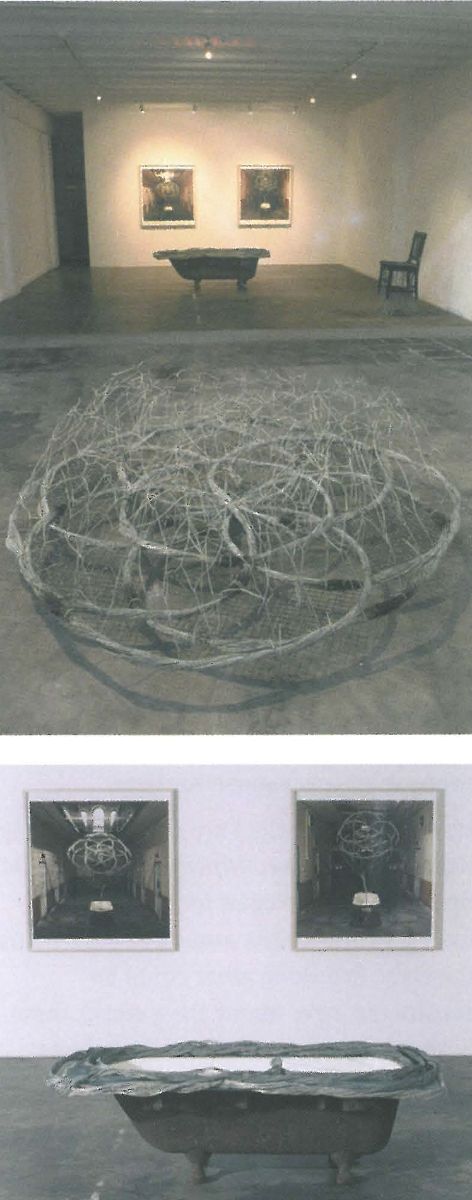

As a backdrop to the sculptural works, Mulhearn has for the first time also exhibited large photographic images of selected pieces. Revealing a growing preoccupation with the artwork as a non-fixed entity, for heliotropic inventory (east) and (west), Mulhearn positioned a claw-foot, cast iron bath with a hovering heliotropic form in the institutional context of the Old Adelaide, suggesting not only the resurrection of matter, but a transformative release from suffering - a redemption. Bulrush seedling which emanates from a rock on the gallery floor, evokes a similar sense of transformation, but additionally in its biblical associations, a place of refuge.

The process is more brutal in anabus as Mulhearn utilises bitumen to blacken and obliterate the clarity of the chair form, ultimately elevating it both literally and figuratively with a thatch of wire. Recalling Warhol's electric chair series, anabus quotes from an art-historical lineage of the dysfunctional chair like Beuys' Stuhl mit Fett (1963) or Mona Hatoum's more recent wheelchair pieces of the late 1990s.

Mulhearn works intuitively, yet the references, both art-historical (Rauschenberg, Merz, Gascoigne, Dine) and otherwise are nevertheless manifold, as he alludes to environmental concerns and political issues, like black deaths in custody. Water, conspicuously absent from the stained, cast-iron bathtub of the oratory signifies with its ability to fluctuate between liquid, solid and gaseous states, the potential for transition. This circularity is (literally) depicted by Mulhearn through the labour -intensive bringing together and welding of the ends of electrical cable.

Similarly, Mulhearn - whose heritage is Anglo-Indian/ Irish and who spent 1999 as artist-in-residence at Andhra University in India - seeks in his art practice a merging (both literal and symbolic) of east and west: the image of the anabus - an amphibian fish, literally a fish out of water - may be instructive in this context. Although Mulhearn speaks often of the 'containment' of his material, he is interested not so much in creating order from chaos, but in attaining a quality of peace. However, the perfect resolution of the circle - with its implication of continual movement and removal of distinction between beginning, middle and end - simultaneously contains and excludes. It is one of several contradictions, which lend vigour to the work for fifth showing - man-made materials which appear natural, a gritty lyricism wrought through a difficult and even hazardous process of destruction/reconstruction and a tension between feeling and cognition.