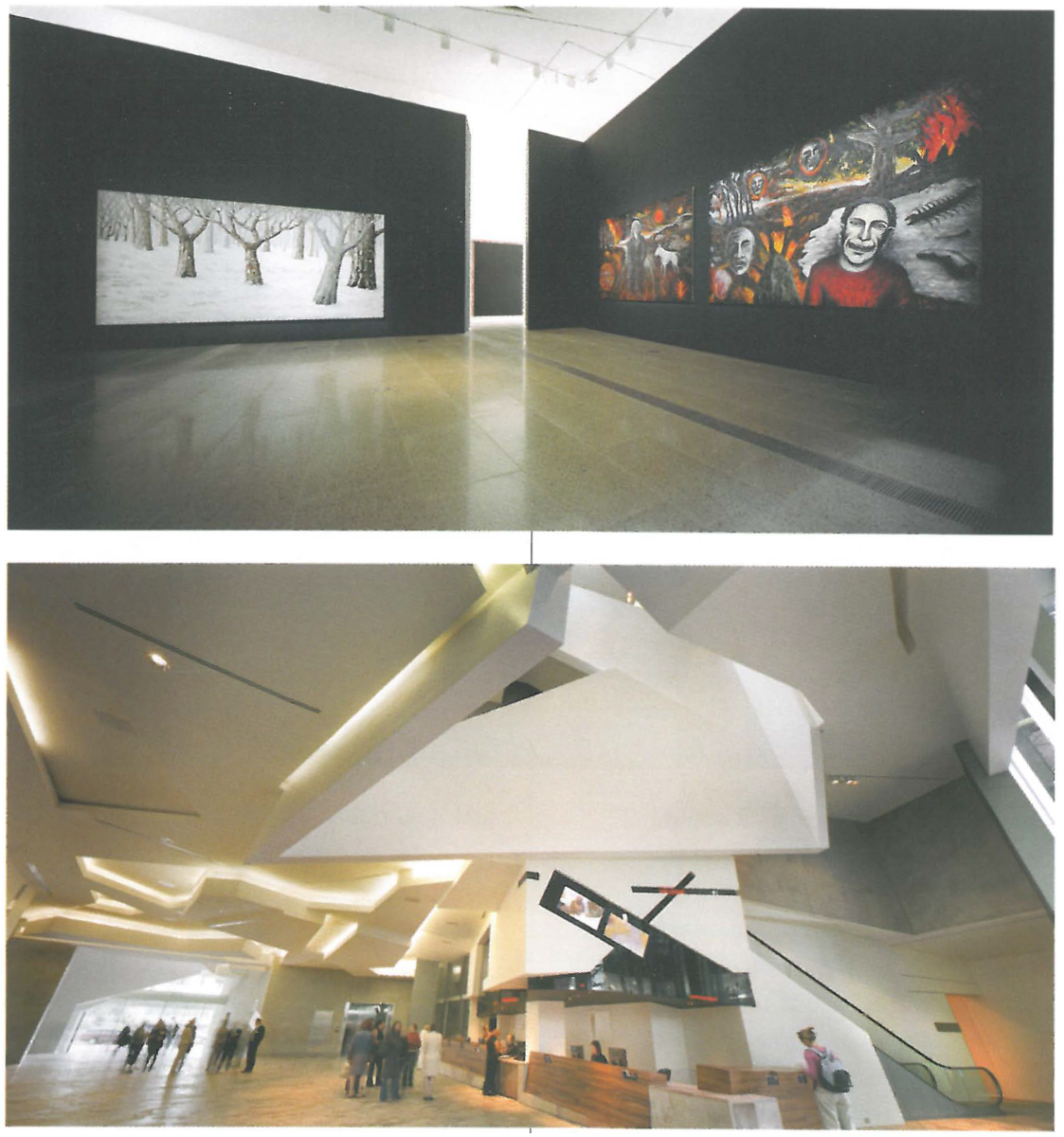

1. 'The Ian Potter Centre: National Gallery of Victoria, Australia' (NGVA) is a major component of Melbourne's Federation Square complex, in turn up there with the Sydney Opera House in terms of tourist attracting potential - or so the Victorian Government hopes. If the buildings of Fed. Square are nowhere near as iconic, tending to crawl across and integrate with their platform rather than soar above it, they impressively evoke the sublimely high pile of cash ($450 million and counting) needed for their facture. It is a relief to report that their overall effect is of huge excitement and achievement.

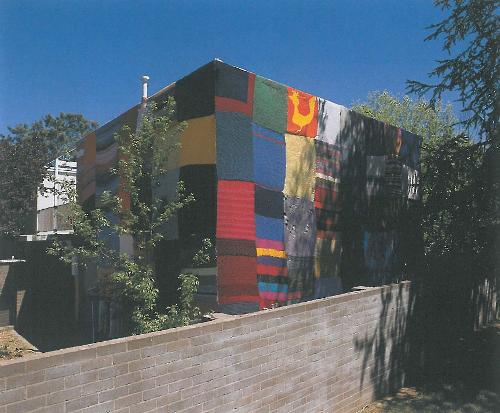

And a certain oddity. It is surprising to encounter Fed. Square's reptilian skin, complete with dominating facets of Kimberley sandstone (plus glass and zinc), in grey, urbane Melbourne. A scaled down version would look more in place in Alice Springs - as would the new Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, its symbolic Uluru to the south.

Fed. Square's rhizomic tendencies, supposedly an echo of nearby street-and-lane patterns, bear the lineaments of computer design, reminding one of Emily Kam Kngwarray's Big Yam Dreaming displayed within. The periodic use of glass walls to make the viewer part of the view is of a piece with an architect's role as über-führer of the artwork's display - a gob-smacking development to this former curator, for all that one understands the new marketability of art-plus-signature building. In the old days we allowed even our directors to interfere with hangs only on severe sufferance. An art-inexpert would have been out of the question. The literalism of said architect, Peter Davidson - of Lab Architecture Studio, London, responsible for the complex with Bates Smart Architects, Melbourne - was sometimes amusing, as where Nolans or a Gascoigne with airy imagery head for the ceiling.

It is more important to note that the architecture plays its part con brio, suppressing misgivings, including a certain disappointment that the NGVA lacks an obvious entry point from St Kilda Rd/Swanston St. The building fairly crackles with dramatic incisions, embrasures and shape-shifting sequences, including periodic glimpses of railway yards and city through a jangle of angles. In time such excitement might require a little sedation, slowing its tendency to pall, and I am sure that the excesses of the hang will give way to greater curatorial sense - and that the gallery will acquire a more manageable name, slipping the word 'national' into the dustbin of history.

None of this matters, for the time being. Unlike Roy Grounds's mournful, stately exercise down St Kilda Rd, if the NGVA goes in and out of architectural fashion, it will stand for a long time as a major contribution to museum building because it starts from a high base of quality. Most importantly, the collection has never looked better, and not just because key works have been scrubbed up and reframed. 'Boring' Buvelot glows confidently in excellent lighting. The bright new galleries generally offer a viable alternative to the established, sometimes oppressive option of period décor without resorting to white cubism.

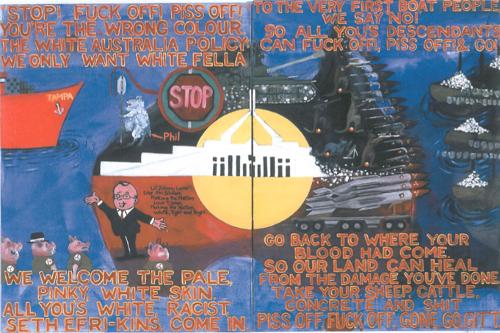

Much has already been said about 'interventions' in the hang, that is, insertions either of non-Australian material lending historical context, or of pieces which offer ahistorical commentary, especially in the form of moralising on matters Indigenous. Some interventions work markedly better than others. In the Buvelot room a minor Barbizon masterpiece by Théodore Rousseau, Bosquet d'arbres, c.1844-1852, gently informs the mix. Brook Andrew contributes an energetic start to the Australian galleries, helped by the wryly humorous title of his piece, Sexy and Dangerous (1996). But did we really require Julie Gough's Chase, 2001, to set us straight about E. Phillips Fox's Landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay, 1770, fourteen years after the Bicentenary of Invasion? Whatever the hit rate of the interventions, there are other instances of curatorial inspiration to enjoy. Move towards the Heidelberg works from the colonial galleries and it is mainly landscapes array themselves before you: progress in the opposite direction and people meet your gaze. A simple but compelling dialectic. Marvellous!

2. Fieldwork - Australian Art 1968-2002: another triumph, I fear (such an apparent surfeit of praise!). Essential for anyone with more than a passing interest in Australian contemporary art. Indeed it spans the very period of contemporary art by one common definition, ie. art after modernism, embracing conceptualism, postmodernism and postcolonialism The exhibition, backed by a book, demonstrates just how roiling was that sequence.

Fieldwork, of course, positions itself against the famous Field, the exhibition which opened the Grounds NGV in 1968. It aspires to similar significance, albeit attacking our times with an historical sweep rather than synchronously surveying a moment. In so doing it demonstrates state-of-the-art curatorial sophistication in terms of historical/theoretical consciousness, achieving lucidity while allowing a necessary complexity.

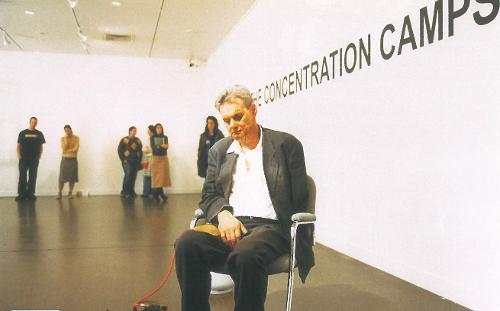

The first gallery includes works by some of the Field artists (Ian Burn, Dale Hickey, John Peart, Mel Ramsden and Robert Rooney) along with recent work referencing that moment, eg Callum Morton's Gas and Fuel, 2002, an à la mode, modelled memory of the building which formerly disgraced the NGVA site. The exhibition proceeds by unpacking some of The Field's directions, pop, minimalism and conceptualism, then moves quickly to the latter's counter, politicised art of the 1970s.

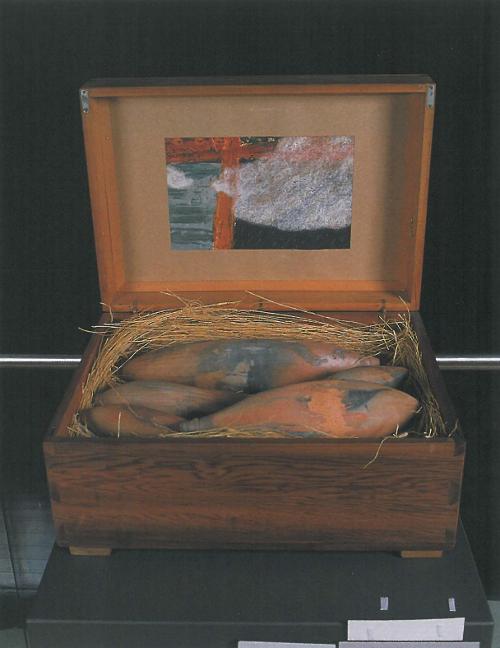

Some of the political stuff looks tired, but never mind: go around the left hand screen in the first gallery, and, bang, you are in Papunya, c.1971: a jump-cut worthy of Kubrick's bone/spacecraft in 2001, even if it suggests its inversion, in terms of closeness to the soil. My reaction was not so much gut as epidermic: instant goosebumps. Other state galleries have acknowledged Papunya, but the body language of their displays suggests a sideshow. Here it is central, as needs be, now, it must. Further NGVA exhibitions will make more of the landscape traces in The Field and ensuing practice, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, as perceptively anticipated by Daniel Thomas's essay, 'Terra', in the catalogue.

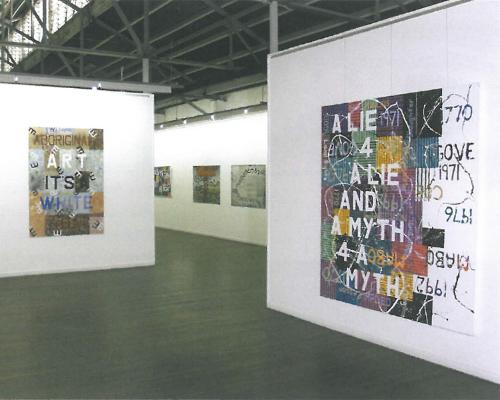

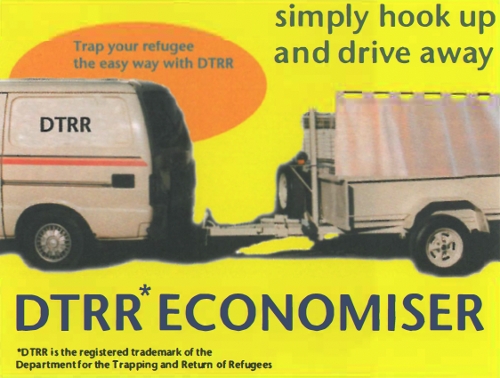

The segue to the Western Desert is the best bit, but there are many other delicious surprises. There is a chronology to it all, but not the dull, plodding sort beloved of 'fair-minded' curators. Half way through the exhibition a room-within-a-room displays Bea Maddock's much valorised yet genuinely impressive TERRA SPIRITUS...with a darker shade of pale, 1993-98, around its outside perimeter, which thus stands for the Tasmanian coastline the work describes. The inside of the room is painted an ultra-dark blue, its lofty walls liberally covered with the work of Peter Booth and Bill Henson. A comparably apocalyptic vision unites Booth's viscerally painted surfaces with Henson's sleek, industrial if sometimes scissored surfaces. One is clearly in the hands of expert exhibition makers: in-house curator Jason Smith and adjunct curator Charles Green. Limited. mainly to the NGV's collection, Fieldwork might not be even their ideal - apart from longueurs in the 'political' section there are one or two slight pieces in the postcolonial area, for example - but one doubts if anyone could have given the NGVA a better debut.

Another room within a gallery, this time filled with Susan Norrie's meditations on painting (including several works entitled Inquisition, c.1999), forms an inward finale, an invitation to reverie in a zone of stylish portention at the end of a tumultuous journey. Elizabeth Gower's reminder of a century's atrocity, September 14, 1901 - September 11, 2001, 2001, wafts against a nearby wall, a reality check in a different if connected direction. Yet something like a final word inevitably emanates from Peter Tyndall's painting A Person Looks at a Work of Art/ someone looks at something...,1985-87. Its reflexivity parallels that of the NGVA, which in its enfolding of foyers, exhibition boundaries and viewers creates more interactivity than might an army of computers.