Deposition 2002, oil on canvas, 20 x 25cm.

It seems almost contrarian, at a time when fashionable taste looks towards the postcolonial and eschews the western tradition, for an artist in Australia to explore the depths and the implications of the northern Renaissance. But in recent years Ruth Waller has done just that.

Of course being Waller, the painter of past pawscapes, her art is far removed from the pretty geometry of Jeffrey Smart or Justin O'Brien. These explorations have an edge, a sense of a world not quite comfortable with itself and its history. Her 'texts', if that is the right word, are Breughel's painting, Dulle Griet (Mad Meg) and Dieric Bouts' The Martyrdom of St Erasmus. There are lyrically beautiful abstract forms making patterns of rhythms - a series appropriately named Sackbutts and Crumhorns. These are more than simple visualisations of medieval popular music. They also celebrate form and line in harmony, visual counterpoint creating music for a time long past, that is also like the present age in its confusion, disruption and intolerance.

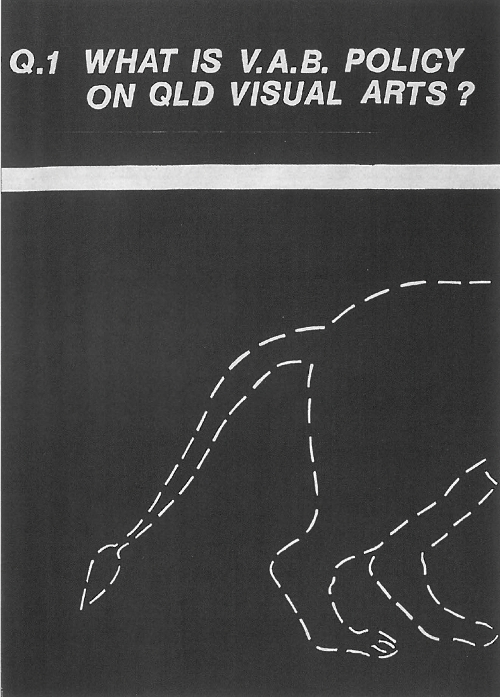

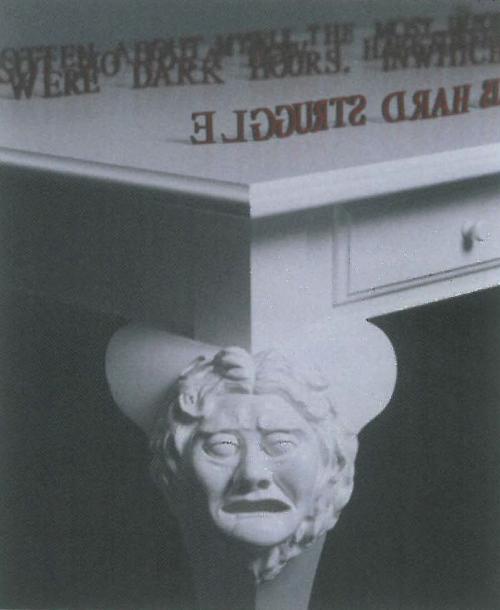

The strongest sense of this world of confusion comes from her Dull Griet series, based on Breughel's painting of a mad woman in the face of war. Although this painting has been celebrated as a 'modern' depiction of lunacy, it is clear that Breughel saw her as a creature from 'the Gates of Hell' through which she passes in urgency and lunacy. Waller then is going to the heart of the western tradition that has women carry the burden of madness caused by war. Her Mad Meg is made of the rubbish she carries, a bleak creature of destruction, almost robot-like as she progresses without feeling in a mechanistic world. She is a woman-machine, out of control avenging as well as despairing, the ultimate being of our modern age who also belongs visually and intellectually to the angst of the past.

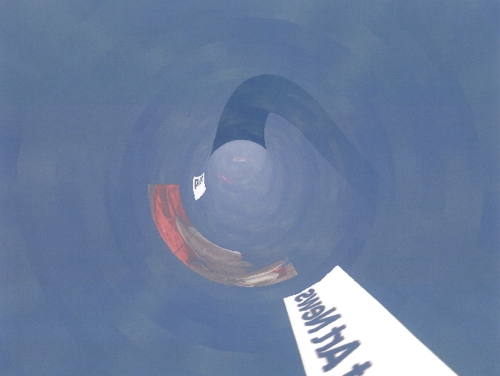

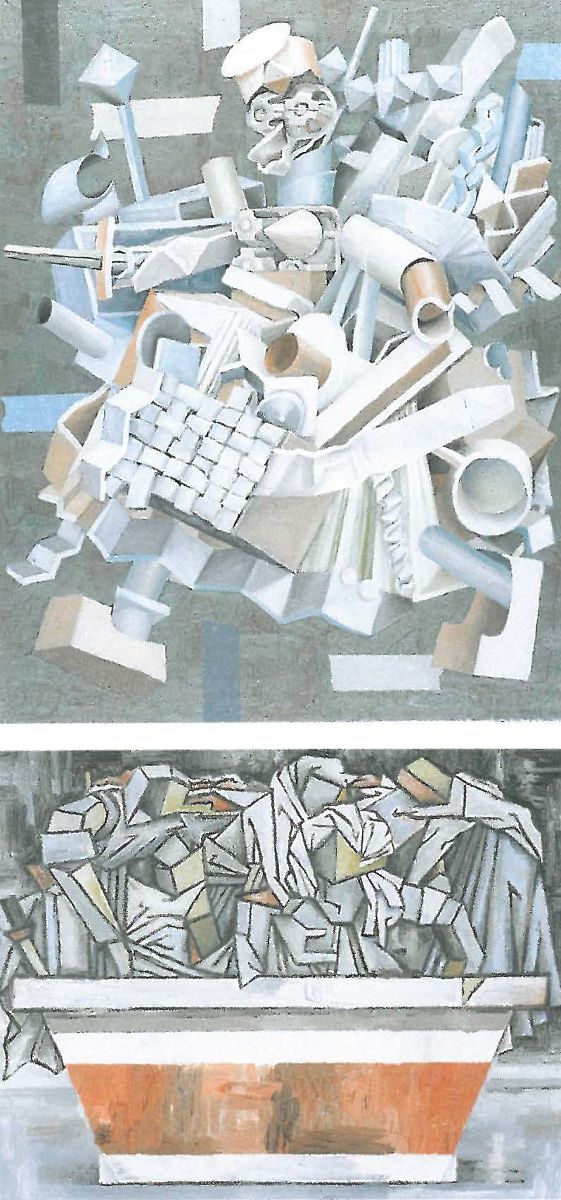

Then there are the skips - elegant shapes in which rubbish may be placed. Waller first saw these skips when she was living in Barcelona on an Australia Council residency and was impressed by their beauty, and the way in which they become the holding place for fragments of people's lives.

The key to this series is one of the smallest works in the exhibition, Deposition. Waller has always been intrigued by the women tenderly taking the dead Christ from the Cross, where emotion and grieving is shown by the fold of the cloth, the angle of the corpse, the bowed heads of the mourners. This Deposition is however different. It is a collection of rubbish in a skip, so arranged that at first the images appear to be valuable relics of the western tradition, but in a skip everything is reduced to rubbish. Other paintings expand the theme - arches and crosses, odd shapes that have double meanings - the structure of western culture, turned into trash. The skip paintings also link to small sculptures on the same subject matter, where the artist plays with the geometry of apparent rubbish. These may have been developed as tools to help her work through her ideas for the two dimensional works, but they stand as small intriguing sculptures in their own right. Waller has made other sculptures. Waller's Dull Greit first saw light of day as two sculptures, and it was these metre high rough unfinished works that later had their portraits painted to make the series.

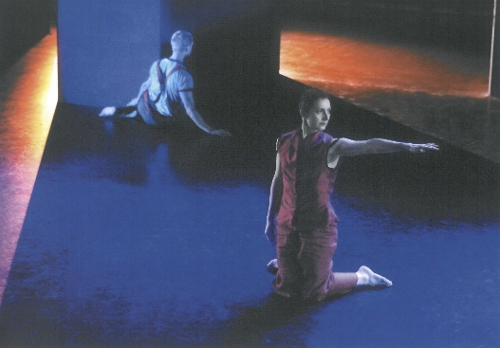

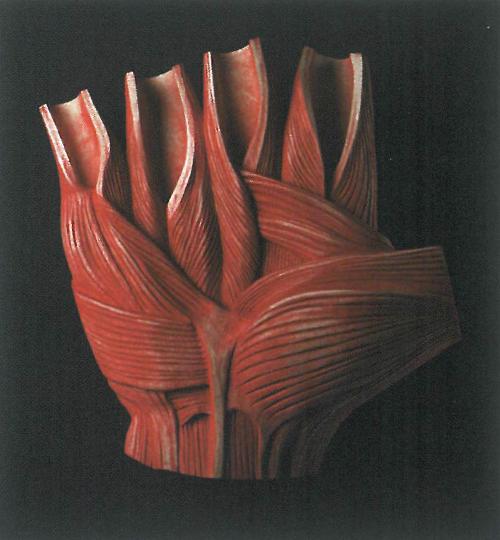

Breughel's Dulle Griet has been described as his greatest work, his personal critique on the folly and barbarism of the Spanish Inquisition, but Waller's other visual 'text' is perhaps less famous. This is Dieric Bouts, The Martyrdom of St Erasmus. For those of us with a secular base, Erasmus is the great Dutch Renaissance philosopher, but the saint, his namesake had a bloodier context. He is usually painted being disembowelled (he is the patron saint of women in labour), and was popular in both the northern and the Italianate tradition. Waller admires most the Flemish tradition, the way the artists invite the viewer to join them in the picture plane.

Bouts' St Erasmus lies there as his intestines are wound up on a winch while the saint, and his torturers, look on in relative tranquillity. In St Erasmsus and the Painting Machine Waller uses the structure of Bouts' painting and the winch to show the miracle of the pictorial space and an investigation of pictorial structure. It is all there on a frame (which looks remarkably like a loom), a construction beautifully painted and gradually dissolving into geometry. It is such a pleasure to see paintings well made and thoughtful, where theoretical considerations harmonise with visual concerns instead of illustrating them.