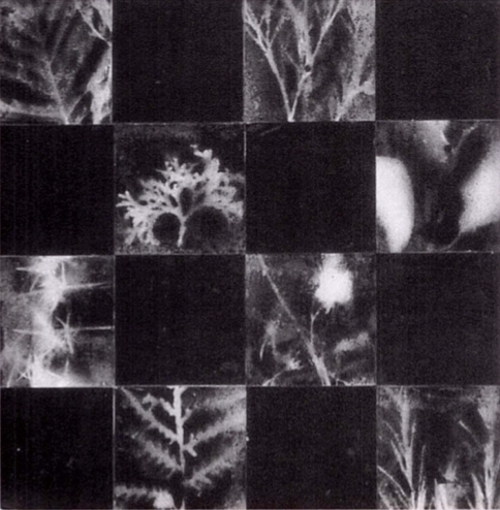

After viewing this exhibition, my dreams were filled with the Glasshouse works. Not so much each individual piece, but the imaginative spaces that Laurence has developed. The sense of movement through the both translucent and densely packed 'forests', a feeling of looking through veils, or faded dusty glass and wondering how to enter, or exit, these coolly emotive environments.

The ongoing concerns of Janet Laurence – explorations of space, engagement with the natural through a construction of the artificial, the development of 'museum' sites, and an elegant negotiation of scientific and natural history motifs – are all apparent in the Glasshouse works displayed at Sherman Galleries. These works belong to a larger collection of engagements with the glasshouse theme capturing a tantalising sense of what the whole may become.

In fact many of these works act as models on a number of levels. Both modelling the 'glasshouse' project and acting as architectural models for potential sites, they bridge that gulf between the architectural model and sculptural with ease. The acrylic panels with their almost ghostly images of glass doors and windows and half seen gardens that make up After Farnsworth House could model a larger work – one in which the viewer can actually enter the space, yet simultaneously the work as a miniature creates its own imaginative labyrinth.

The wall-mounted overlapping panels of Green Space 1 & 2 with their images on glass of deep green hedges hinting at topiary mazes also construct labyrinths; as the panels overlap so they invite us to enter and then once entered, find ourselves in an unnavigable space. We are subsumed into these both natural and totally constructed sites, we can become lost. And loss, as a theme and a motif, echoes through these constructions. Laurence allows us the nostalgia of this loss while working towards acts of preservation, memorials to botanical specimens that are endangered or gone.

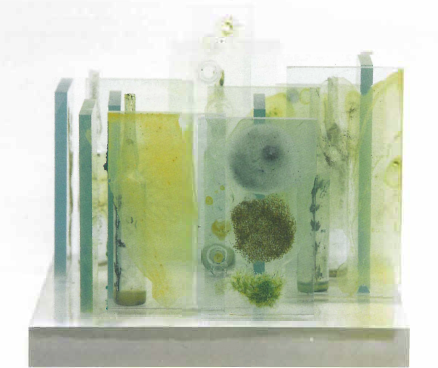

Medicinal Garden (for endangered plants) 2, 3, & 4 all act as testaments to the loss of botanical specimens. Laurence inscribes acrylic sheets with the names of lost plants (and what deliciously evocative and romantic names they are: Simourabaceae Quassia, Thymeleaceae Pimela – like the most melodramatic of C19th heroines) and also displays vials holding plant samples, minerals, and liquids. Distilled essences, or elixirs as they become in the Botanical Elixir Bar a model constructed of vertical panels holding vials of the essences of health-giving plants, in the centre of which is a space for the 'barman' to serve us, or to doctor to us.

The vials of botanical specimens are like a pharmacy of the past or perhaps like a most contemporary form of flower pressing, reserving through careful preservation a pallid essence of the original. They capture a feel of faded gentility, of the dusty catalogued confines of a natural history museum. The museum as a memorial, a site and repository of that which has died, is alluded to in the steel display stands that Laurence uses (aptly, perhaps, they also have something of the dissecting table about them). This museum, the Glasshouse as a whole, catalogues absences in our catalogue of natural history, literally inscribed in the work Trace Elements (Botanical – endangered), or figuratively through the works as a whole, creating a roll call of remembrance.

Laurence creates these memory sites using the most modern of materials – acrylics, plastic, perspex – yet they are transformed (an alchemical act of its own that circles around the alchemical references of the vials) into something nostalgic. The pale greens and soft white of these materials could be something sun-faded, worn, aged. These modern materials carry something desolate about them, a desolation that is made clear in the Botanical –winter works of the Glasshouse Series. The modern artificial material is used to represent, and is deeply implicit, in the destruction of the natural, an ambiguity that is both subtle and deeply pleasing.

And yet a glasshouse, despite its evocative connotations of a particular social history, is also a site of growth and indeed renewal. There is however, none of the hothouse flower about Janet Laurence's works – these are calm meditations on that which we have lost, reminders and 'museums' of the endangered; the glasshouse a chance to preserve and perhaps generate a type of new life for these specimens, ghosts captured as echoes and reflections in these beautiful constructions.