When pattern becomes the subject for a group exhibition it is as if the participants are acknowledging the compromise that awaits their work. After all, pattern implies conformity – the overlooking of differences. Pattern organizes things into categories of likeness but at the same time it creates differences of relativity from within a category.

The artists in this exhibition employ a self-conscious literal approach to the materials they use, in order to reveal as simply as possible patterns and boundaries formed by categorisation. What is the pattern conforming to and what is being overlooked? Does pattern occur through mere inattentiveness or does it reflect a more profound structure in our ability to perceive the world?

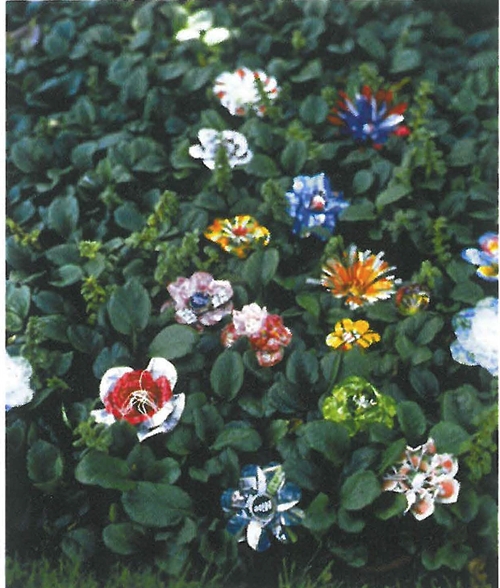

Inspired by a Baroque sense of fluidity and sensuousness, Paul Zika's Cornucopia series consists of two pairs of two, three dimensional cut-outs, repeated and inverted. They're layered again with a range of brilliantly coloured speckled impasto and gilt paints. The form of each section is articulated by a Big-Bang-like expansion from a central point, increasing in complexity towards the perimeter. At this edge, despite the repetition of their ground, it's as if the dissolution of the picture plane is complete. Structure and incidental appearance seem to meld.

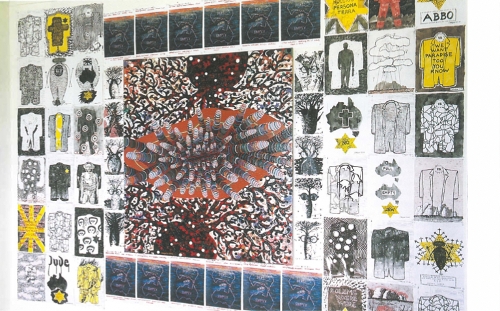

Rather than excess dissolving the picture plane, Michael Muruste's paintings rely on a simple repetitious interruption of it. Evenly spaced horizontal slats are fixed to a support and painted over with lines and dots, which seem to trace the contours of their corrugated surface. In front of these works, your eyes follow the lines but fail to easily see which level the paint is on. This reverses the usual way in which the picture plane operates. Instead of a single flat surface that the viewer sees through, they present two physical planes, which appear to be one. Because you know there are two levels, the paint, despite its thickness, hovers between its materiality and optical illusion.

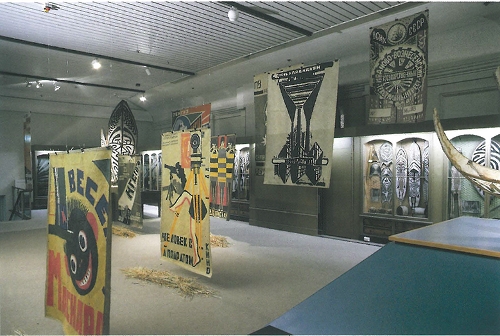

The compositional harmony of David Hawley's Alternating Monolith and Pulse possesses a more humorous use of literalness. The baldness of the materials used is contrasted with the sense that they are somehow fake. Like theatrical props left backstage, it's as if they're not supposed to be seen close up. Hawley shifts normal relationships of surface to integrity, forcing his materials to play out of character. Paint is piped like icing for a cake and hessian becomes a pattern. Substance becomes decoration, the ground ornamentation. In Alternating Monolith the blue colour shifts between surface, substance and ambience and just when you think a wholeness has been achieved you walk around it to discover that the side of the work facing the wall is blank.

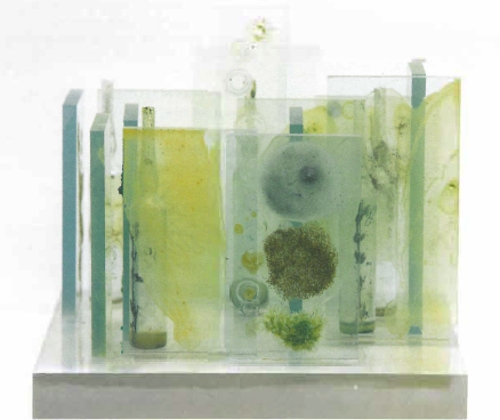

Neil Haddon's modular grid paintings tread a finer line in terms of mistaken identity, and play off the grid as an ideal, with the need to return your attention to a specific surface. They revisit the aesthetic of 1960s Modernist abstraction but deliberately upset formal sufficiency by emphasizing the mistakes that could occur in the process of making them. The grids don't match the proportions of the ground; the series of coloured bands follow a perverse Minimalist logic, or the picture plane appears damaged through some kind of corrosive reaction. The precision of these works suggests a closeness to perfection but at the same time the slick surfaces maximize optical coincidences. You wonder whether optical illusion is material or ideal, specific or abstract.

Lucia Usmiani's Golden Pash also contains optical puzzles but within an uninterrupted overall design. Using pins to make a grid, cut out aluminium strips from drink cans rest on and around them, forming an intricate web. The individual components become lost, in a flickering array of gestalt patterns on a curved wall. The most compelling aspect of this non-centred structure is that your perception of it reflects your own proximity to it. The depth of the strips appear greater at the edges of sight of the contoured wall and of the light source. Golden Pash appears to follow you around the gallery space.

Besides the aesthetic choices made to give formal boundaries to these works, optical crises - the conditional interaction of looking - are presented as that which saves them from being overlooked. But, at the same time, at the heart of this contingency, doesn't our sensual grasp on the world form yet other patterns of limitation..