Melbourne's Gantner and Myer families formed a Collection of Aboriginal art from Central Australia, the Kimberley and Arnhem Land in the later 1990s, and have just donated it to the Museum of Victoria. In 1999 the works were displayed in San Francisco, in an exhibition for which Jennifer Isaacs, curator of the Collection, wrote a substantial catalogue. A reduced version of this exhibition, with the same catalogue, was recently presented in Brisbane, prior to touring in China and Japan.

Travelling Indigenous art exhibitions on this scale are infrequent enough to invite comparisons between them. How has the art changed, what have become the major areas of interest, which have become the most prominent artists since Dreamings in the 1980s or Aratjara in the 1990s?

It is probably unrealistic to compare any exhibition to Dreamings, the survey show that introduced the Western Desert painting movement to the Western art world in New York City in 1988. Spirit Country also puts a very different interpretation on contemporary Australian Aboriginal art from the 1993 Aratjara exhibition, which included city artists. The Gantner Myer Collection apparently includes bark paintings carvings and weavings from the North, but this exhibition is tightly focused on desert canvases.

Because it is an exhibition of works from a museum, formed by distinguished philanthropic families with the curatorial guidance of a leading authority on Aboriginal art, viewers could be forgiven for expecting to see a grand and magisterial survey of old masters. This is not the case for a couple of reasons. The majority of the most memorable works in this collection are by women, not the senior painting men whose early boards and canvases have acquired mythic status (with some help from the auction houses). Although the Spirit Country catalogue illustrates a few older works in the Collection (not shown in Brisbane) including three classic early Papunya boards, this is primarily an exhibition of artists who emerged in the 90s. Already the cost of acquiring a representative collection of the best paintings spanning the full history of the Western Desert movement would be astronomical. The large sums of money involved would be paid to other collectors, not to the artists.

The Gantner Myer Collection was formed quite genuinely as a survey of new art. It has therefore actively participated in the ongoing development of art as a social focus for Indigenous communities, and it has given financial support to contemporary artists. A catalogue introduction by Hetti Perkins, titled Our Painting Is a Political Act steers clear of the sentimental new age spiritual reverie that such an exhibition is likely to induce in non-Aboriginal viewers, and acknowledges that painting and patronage can change lives.

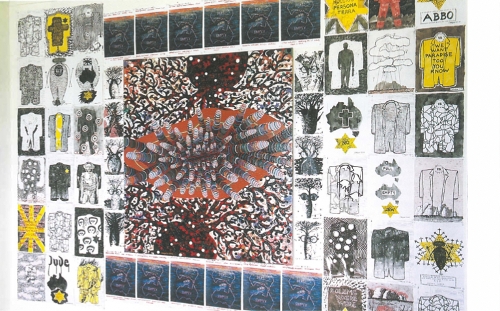

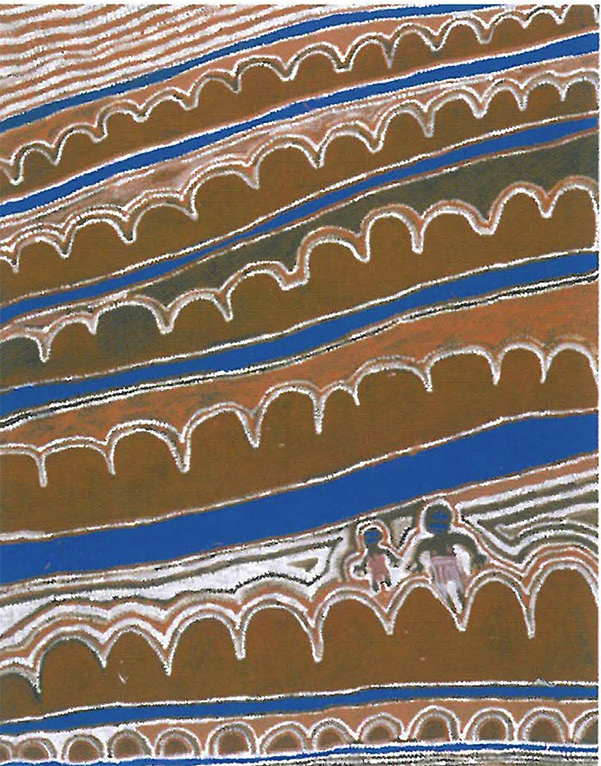

Many of the artists in this exhibition are not very well known. There are famous names from Papunya, with slightly stiff late works by Anatjari Tjampitjinpa and Yala Yala Gibbs Tjungurrayi. The leading Utopia artists Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Gloria Petyarre are there too, not represented by their finest paintings. Generally it is the lesser-known painters, represented by splendid works, who make the exhibition. There are exceptional paintings by artists from more remote communities such as Kiwirrkura and Lajamanu, and art centres that emerged later than Papunya and Yuendumu. The importance of Haasts Bluff is clearly demonstrated, with fine works by Narputta Nangala and one by Mitjili Naparrula that is about as delicately seductive as a painted surface can be. Many of the really good Papunya paintings turn out to be by the wives and mothers of better-known male artists associated with that community. Without forcing the point, Jennifer Isaacs seems to be illustrating a somewhat revisionist history of the most important development in later twentieth-century Australian art, which the Western Desert painting movement surely was.

Spirit Country also provides a useful overview of the diversity of painting technique in the Western Desert. Dot painting caught the popular imagination twenty years ago, possibly because of the shimmering optical effect it often produces. Its varying degrees of precision and broad range of effects are evident in this exhibition, but so is Pintupi hard-edged geometric minimalism and the much more loosely gestural brushwork associated with women's body painting (which appears strongly on canvases from Utopia).

With the growing market for Aboriginal painting came greatly increased attention to quality and durability of art materials. Much more respectable art objects have now taken the place of the earliest, rather roughly made paintings stained with the red dust of the Centre and the urine of camp dogs, which are now so treasured. Fortunately the pressure to make paintings with a more dependable life span has not affected the vitality of their execution. What may once have seemed like a hesitant wobbly charm when artists painted on bits of discarded building material, can be appreciated as sensitive painting technique now that it is done on large pieces of the best canvas.