Kia horoia taku porokaka ki nga wai o

taku ake whenua

Let my neck be washed by the waters of

my own land

It is not that online exhibitions are waiting to be discovered. Indeed, they have been around for over a decade now, and it is common for 'online' artists and curators to present practices in this way. I've been returning to the website day after day and it became clear to me as to what appeals about the exhibition.

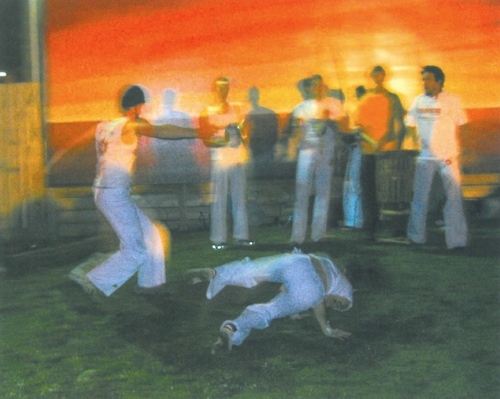

Browsing the website for me is like selecting tracks from a great indigenous CD collection. Being able to select your favourite 'when you want' is good, and it is ok that you prefer certain ones on different days. The range of imagery brings into play modern and contemporary sounds including Pacific rap and reggae beats; a suggestion of country appears here and there; occasionally a rock' n roll 'cover' comes through, and chants are evoked throughout. For the most part, there are 'a whole lotta rhythms goin on' and are seriously bursting through.

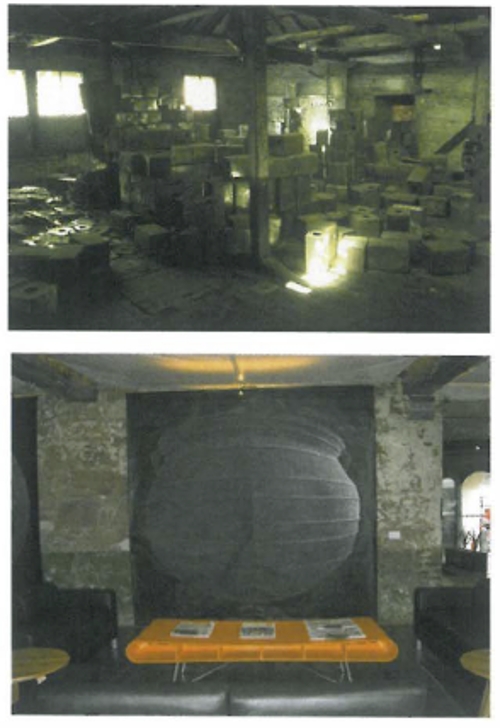

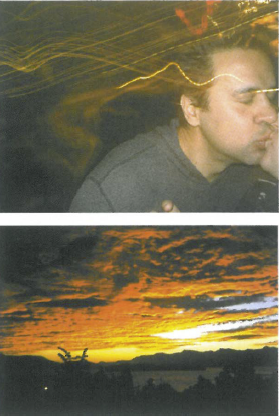

The medium of digital photography can help explain the influences that artists are exposed to, and the exhibition title provides the context for the selected works.The luscious depictions of people and place come framed with emblematic references to how indigenous artists experience place, and the results are, well& truth-seeking. Lonnie Hutchinson's (Ngai Tahu, Samoa) images a resplendent and bejewelled Lyttleton harbour, a place the artist is constantly drawn back to. Tribal connections to the region are a recurring element in her practice and while Ngai Tahu relationships are implied through the title Whakaraupo (Lyttleton Harbour) 'after-dark' is a time when unanticipated strife can emerge; and Lyttleton certainly has that kind of history. Jenny Fraser's expansive view of Looking towards Yarraba caught me by surprise. Almost twenty summers have passed since I took in that view& but it was Fullmoon at Cedar Bay that touched me. Perhaps it is to do with memories of North Queensland dark nights and the wet tropical rainforests that run right down to the water's edge. Maybe it is the fact that the place is inaccessible by road. While Mangkal Mangkalba or Cedar Bay gained popular notoriety in the 1970s when hippies moved 'in and out', it is the more enduring legacy of the site that is moving; with the added knowledge that Aboriginal tribal groups have guardianship control within the region.

So, here is the thing. In customary art practice, artists drew from nature to express, evoke and relate experiences about people and place. They communicated these ideas through narratives that they performed in rituals; they talked about it together and passed knowledge on to each other through oral history. Significantly, they left a legacy of distinct indigenous art practices. The ancestors over thousands of years held complex and elaborate associations with land, sea and sky that were meaningful to them. That was the way it was for them and it reinforced their identity as aboriginal, native or indigenous people.

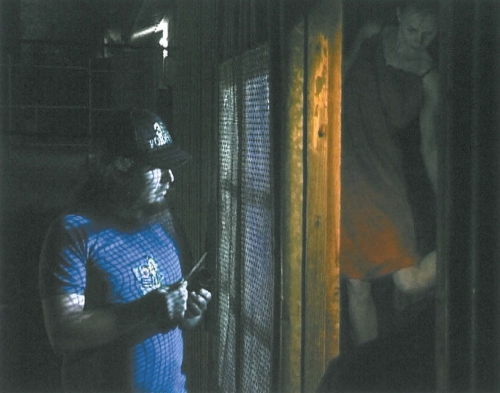

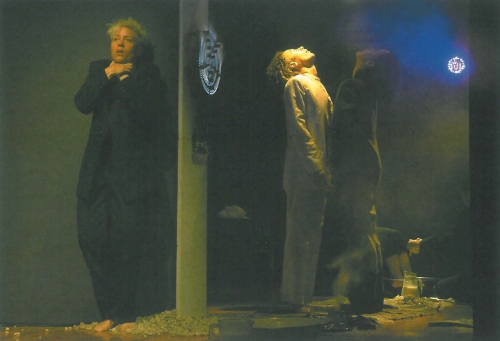

Using modern technologies, descendants of many tribes (cyberTribe) continue to draw on links with nature. They have an appreciation of their environments and are enabled to 'name' and image their interpretation and experience of place Native Canadian artist Terrance Houle's (Blood Tribe) portrait is captured in Red Handed, a digital photograph taken by Jarusha Brown. Houle's involvement with his community is extensive; he travels to perform at powwow trail dances and he represents his tribe in Native ceremonies. Houle is presented here, adorned in traditional dance costume. Dance costumes such as the one he is wearing have become icons of Native Canadian people yet are probably not well understood given the knowledge and relationship one would need to have with nature to produce such costumes. Like Hutchinson and Fraser, Houle is conveying more than the eye can see, such as traditional relationships, values, beliefs and cultural history. To this end, their 'voices' follow pragmatic processes and values and we are surely blessed that they tell such vital stories. The artists offer spectacular and comprehensive views to amplify indigenous spiritual, political and cultural interiors that are acknowledged by indigenous people.

What 'Out of the dark' achieves is that it re-presents the environments in which contemporary Aboriginal, Native and Maori artists live, work, play, and return to time after time. They expose, connect and gather together moments in time and space, and affirm what we know to be true& we have endured much, overcome insurmountable odds and continue to grow from strength to strength. The exhibition curated by Banjalung artist/curator Jenny Fraser does not define contemporary indigenous practice, rather it promotes the realities and sensibilities of indigenous artists, whom Fraser brings into the light.