The exhibition Object/Subject aims to chart the progress that an object takes in order to become the subject of an artwork. To this end, the exhibition features the work of eight painters and photographers, with each artist's practice being defined in terms of its subject matter.

In much of this subject matter we find an affinity for the overlooked and the incidental. The clearest example of this is found in the paintings of Arryn Snowball, which are based on photographs of steam escaping from the mouth of a kettle. In Snowball's work vaporous forms emerge from the darkness, lending the suburban kitchen the aura of a Romantic landscape. The relationship between painting and photography (or at least between image and source) is a recurring theme in the exhibition. In Richard Muldoon's Circular Highlights series, we are presented with vivid renditions of incidental background details from photographs – specifically those points in the background where the lack of focus dissolves the subject in pools and eddies of light.

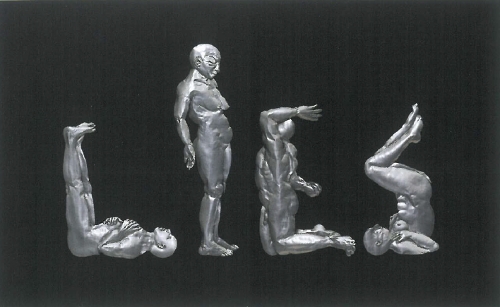

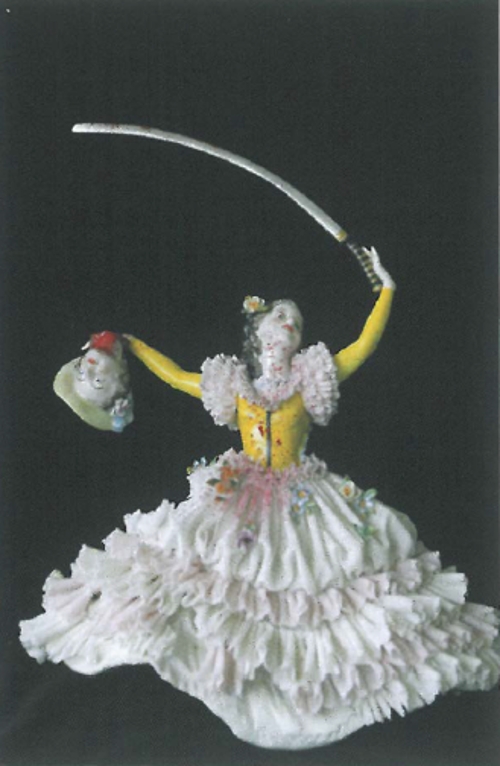

Also working from photographs, the work of Michael Zavros refers not so much to everyday life as to lifestyles of the rich and famous. Zavros' intimate, meticulously finished paintings document a material world of luxury and opulence that seems only to exist in the pages of magazines and popular imagination. In this context, these works appear ambivalent about their subject, seeming to simultaneously adore the baroque surfaces and prestigious environs that they depict, while at the same time highlighting the emptiness of their aspirations.

In contrast, the paintings of Natalya Hughes and Allyson Reynolds tread the line between abstraction and representation. Using digital imaging, Hughes recomposes images of Japanese woodblock prints, removing or obscuring parts of the image to produce a floating world of fragments on a monochromatic ground. The digital sketch is then rendered in oil paint. The process of translation becomes important here; translation across cultures, but also translations of scale (in this case from intimate to billboard), medium (the flatness of the woodblock to the thickness of oil paint), and content (from figurative to abstract). While areas of details and ornamentation betray Hughes' sources, the paintings of Allyson Reynolds feature lines of oil paint dragged across the surface in what appears to be an entirely abstract composition. The fact that these patterns are actually based on images of moth wings as seen under a microscope cannot be discerned from the images themselves, rendering the relationship between image and source highly ambiguous.

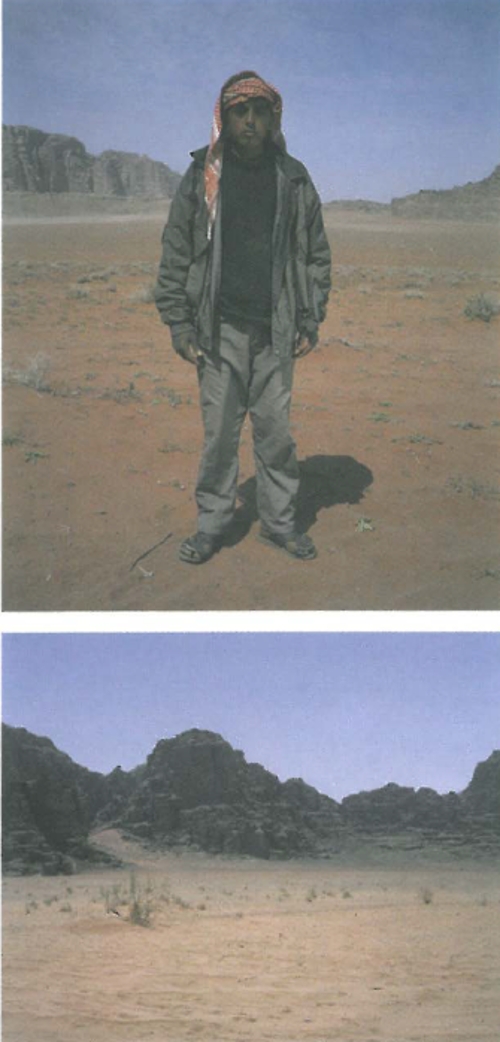

For me, the exhibition is dominated by questions of process and the relationships between painting and photography, figuration and abstraction. The inclusion of the work of three photographers serves to polarise the exhibition along these lines. The work of Robert Mercer would seem to sit most closely to other works in the exhibition, ironically because of his painterly process rather than his subject matter. Mercer makes Polaroid self-portraits that are etched into with a bullet while the chemicals are still setting. The result is a series of mottled, distorted images of the artist's visage, the image appearing to decompose before our eyes.

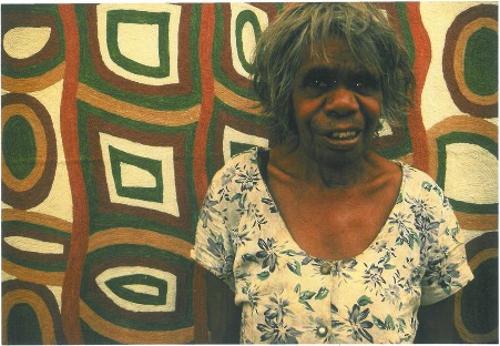

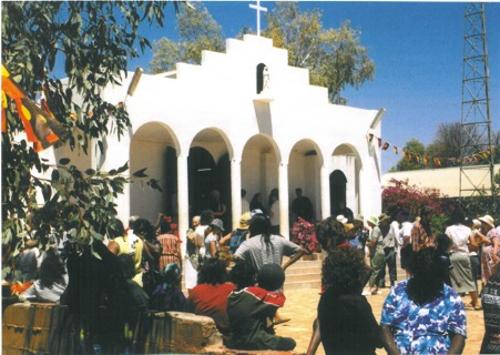

Pursuing a more documentary approach, Brett Adlington's photographs present quirky, ever so slightly surreal views of the Gold Coast. More particularly, Adlington composes his photographs quite specifically to document both the landscape and the things that obscure it. This includes romanticised billboard images of the landscape, which squeeze into the frame alongside vacant lots and constructions sites. Angela Blakely's series Keep passing the open windows also documents the urban landscape. Apparently banal suburban sites are photographed in daylight, in a direct, documentary style that suggests little of their sad histories. The short captions that accompany each image transform our understanding of these images, revealing that they are actually sites of youth suicide.

The emotional power of Blakely's photographs further highlights the disparity between many of the works in the exhibition. While the looseness of the curatorial rationale allows scope for a good collection of individual works, for the most part the connections between them are difficult to fathom. Perhaps the real object of the exercise is in the subjectivity of the viewer.