I was expecting this issue to follow a certain line. It seemed necessary to address the repression of the hand made as part of a process of commodification that denies means of production and celebrates the brand. Certainly, many writers in this issue have pursued this line with verve, but there are some surprises too.

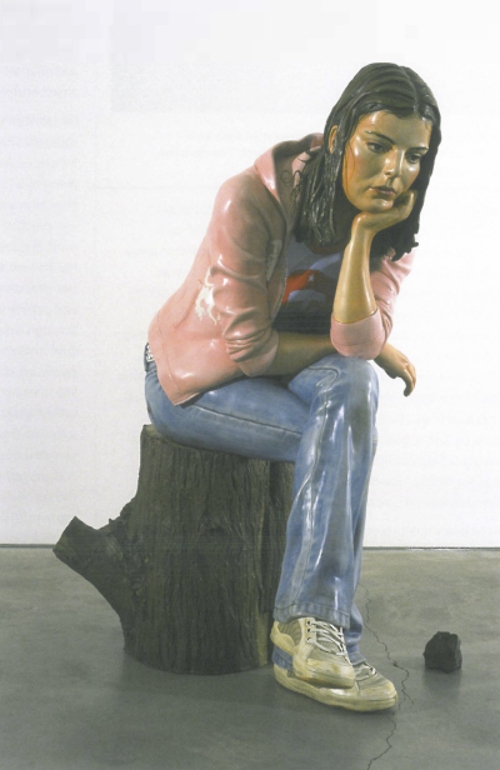

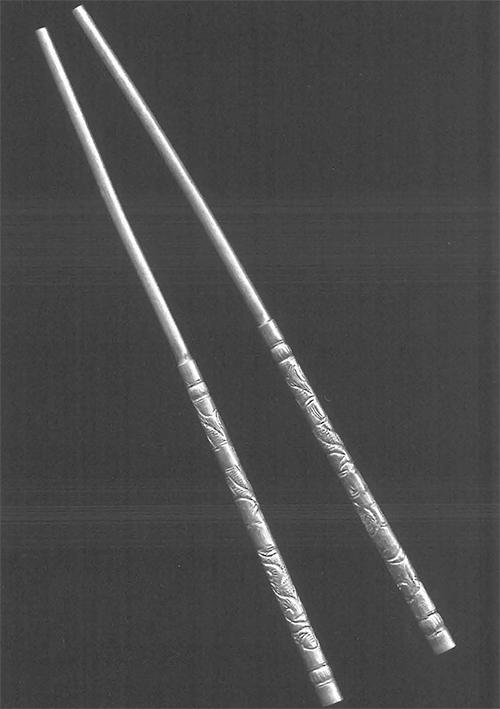

The theme has been prompted by the selection of Ricky Swallow as Australia's representative at the Venice Biennale. The art of his predecessor Patricia Piccinini involved commissioning a team of technicians to execute her designs. In Piccinini's case, it has not seemed appropriate to ask the question whether it matters that she does not appear to directly make her work. In Ricky Swallow's case, however, his personal involvement in carving seems important in the dissemination of his work. Would Swallow's art be any less if he delegated his labour? If not, then why do we celebrate his physical involvement?

This takes us into difficult water. We need to be careful we don't lapse into a tabloid inquisition about artist swindlers who get others to work for them while raking in the dough. Such simplistic dramas don't account for the skills required to manage a technical team. The best antidote against the mob mentality is information: getting perspectives from the different agents and understanding the technical processes helps us appreciate the complexity of the artistic team. Damiano Bertolli's article on Ricky Swallow and Nicki Harvey's profile of Jan Nelson go some way towards this.

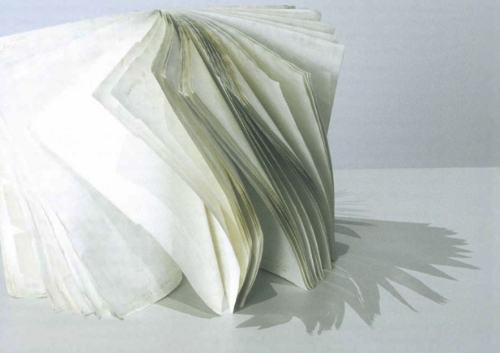

A more intelligent – but still melodramatic – tack plays out the issue as a contest between human and machine. As the principal villain in this drama, the machine takes away meaning from objects. The machine removes traces of the maker and is dumb to the subtle language of materials. Un-homogenised organic materials are put aside, in favour of moulded substances, such as acrylic. Man versus machine is an epic drama that has involved the broad spectrum of artists, ceramicists, darkroom photographers, painters, printmakers.

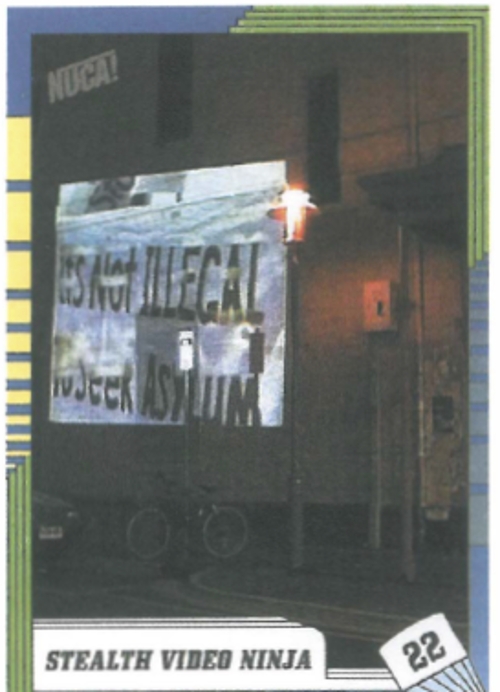

The apotheosis of this battle occurred at the turn of the millennium, which true to the eschatological infrastructure of western society, was cast as a great escape from the material world. The information superhighway was leading us to a Neo-Platonist nirvana of 24/7 win-win virtual solutions.

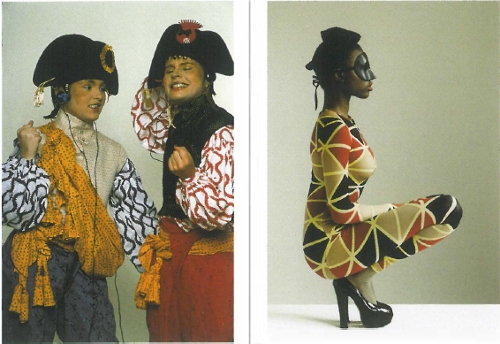

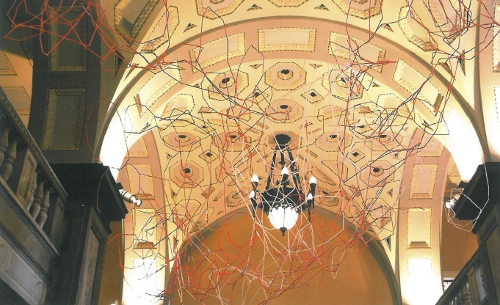

It seems the momentum along this trajectory is slowly ebbing. Digital technology is becoming absorbed into our everyday life and thereby loses its escapist meaning. Design is moving away from a nineties techno-fetish to the earthy textures of clay and hessian. Fashion embraces the ragged edge and exaggerated traces of handiwork. And graphics indulges hand illustration as relief from the glossy PhotoShopped veneer. Humans are extricating themselves from the matrix, nature is re-sprouting.

This argument is played out in new and interesting ways. Martin Jolly and Les Walkling offer powerfully opposing views on wet versus dry photography. Peter Timms and Mark Thomson provide engaging critiques on anaesthetised consumerism. Sue Green and Brigette Cameron consider the return of knitting. Eliza Downes, Peter Hughes, Margaret Baguley, Margot Osborne, Alison Alder and Ainslie Murray discuss the creative potential of the handmade. Suzie Attiwill and Grace Cochrane explore different sides of the issue. With taut irony, Robert Cook considers the fateful appearance of the Walkman. And lest we forget, Leonard Shapiro discusses the hand made from the perspective of those who rely on it for daily sustenance in South African villages.

But I didn't expect the arguments presented by Justin Clemens and Kit Wise. Both avoid considering the hand as something that adds meaning to the creative process. In fact, they argue precisely the opposite – that it is the nature of the hand to take meaning away. In a smart world of inescapable order, the hand can be seen to offer critical breathing space of random disorder in which life can emerge. I am still thinking about their contributions, and you may too.

As material began to come in for this issue, it was apparent there was much more to say that couldn't be accommodated within the covers of Artlink. Some of the articles that could not be printed in full will appear in the online journal craftculture.org. Along with online forums, these articles should help draw attention to this issue from far afield.

This issue fits into a broader context. As part of the Visual Arts Craft Strategy, Craft Victoria is developing a story of 'a future at hand'. It positions craft as a tangible art form that re-orients us towards place and body in an otherwise increasingly distracted world. This theme is played out globally in the South Project, which includes creative strategies to 'rediscover the common'. Locally, it also promotes the 'business at hand' through Craftbase, an agency for developing collaborations between designers and makers. As well as servicing Victorian craftspersons, we hope that Craft Victoria will provide a lens for others to focus on what's at hand.