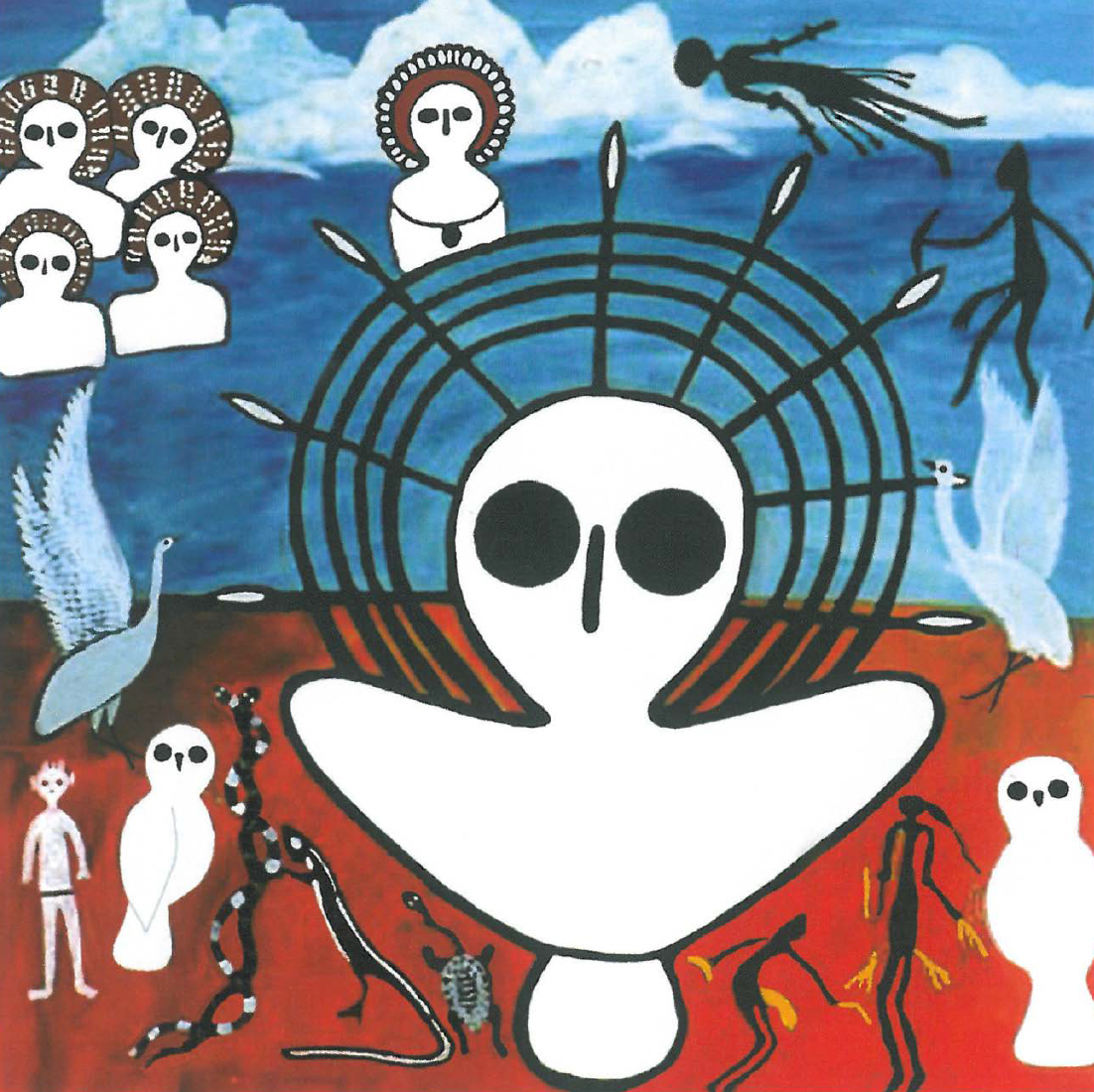

By 'freshening' the paintings of the mythical and elemental Wanjina on the rock sites in the Kimberley region of the north west of Australia, the local indigenous people are participating in a belief system that extends from the time of creation, (the 'Lalai') through their present day-to-day lives and to their future on that land.

Their applied belief system is both spatial and temporal and encompasses the totality of relationships between living creatures and the environment:

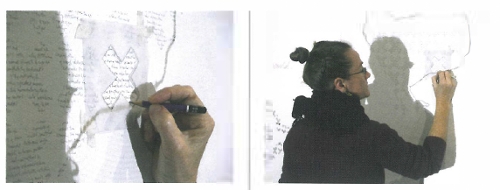

"they did not create original paintings of the Wanjina, rather it was their duty as descendants of the Wanjinas to renew their imprints by repainting them with charcoal and ochre. By keeping the paintings 'bright' and 'fresh' the world would remain fertile, rain would fall, plants and animals would be abundant and men would be able to find the spirits of their children at Wungurr sites across the land and in the sea. Throughout their continued participation in these reciprocal acts between humans and Wanjinas, Aboriginal people were able to sustain their world's finely tuned cycle of life." [p.32]

By recording the issues and events that impacted on the life of Sam Woolagoodja, Donny's father, the authors of Keeping the Wanjinas Fresh are able to provide a very readable historical and personal biography of a man whose life through the 20th century may be seen to represent the impact of colonisation on Indigenous lives. It engages the issues of his time in the personal narrative.

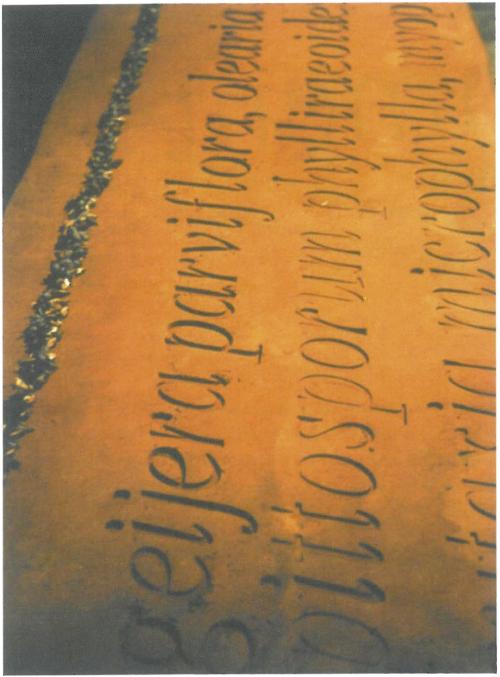

But it is not just a good read: it provides important text on art works from that area (both rock sites and boards/canvases), glossaries, lists of clans, countries and languages, maps of the area, an extensive bibliography and functional index. A book that has bridged the gap between interested lay reader and scholar, it includes notes to the text at the back of the book for readers who wish to follow up issues in more detail.

The political and the personal, the global and the local are intertwined seamlessly. Laws and moral precepts are illustrated within descriptions of daily lives, interdependencies between groups are explained with practical examples and ways of explaining the world are exposed in the stories told to children.

Descriptions of survival techniques, such as grass burning and repainting the rock art sites, are presented in language that attempts to evoke the oral traditions of the local storytellers. It is ecological sustainability in practice.