As the sun eased its way towards the horizon, setting the sky above the Arafura Sea ablaze with orange and gold hues and silhouetting the distinctive foliage of the pandanus palms, the crowd swelled on the green lawns adjacent to the MAGNT cafe. A gentle warm breeze washed over the scene. The ambience suggested a Top End folk festival with loud open-neck short sleeve shirts, sandals, bare feet, flowing cotton sarongs and frocks, occasional glimpses of dreadlocks, fragrances hanging in the air, glints of piercings, small children being nursed or playing about, elderly people with walking sticks, and skin tones of all hues from palest white to gorgeous brown/black. Suggesting otherwise were the smatterings of silk, linen and gold. Cheeks were kissed, hands shaken, for the more intimate or effusive there were hugs and the buzz of conversation filled the air as Aboriginal artists, their minders, art dealers, aficionados, collectors from all over Australia and a good number of locals came together to celebrate the premier national Indigenous art event. Somewhat surreally many of the 500 or so audience members were holding or sitting on matching tartan blankets handed out en masse with bottled water – a surprise gift from the corporate sponsor in lieu of the more usual opening night beverages and nibbles. This year it was BYO picnic and grog for the occasion.

As darkness came our attention was drawn towards the stage. We were approaching the final act of the drama that is now the Telstra National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award (NATSIAA).

The main exhibition space of MAGNT is temporary home to 103 extraordinary Indigenous artworks. Entry to NATSIAA is open to all Australian Indigenous arts practitioners and there is no restriction on subject matter. Prizes of $4000 are awarded for four different media categories (Bark Painting, Works on Paper, General Painting and Wandjuk Marika Three-dimensional Memorial Award) and there is an acquisitive First Prize of $40,000.

Preparations for the Award started in March when Indigenous artists from every part of Australia, many of who are represented by community art centres or art dealers, were invited to submit entries. The Award has no theme and no constraints are placed upon entries although MAGNT has always envisioned the Awards being the major survey of contemporary Indigenous arts practice and aims for equity in representation. The entries are assessed by image – a response to the challenge of physically dealing with hundreds of artworks. Once upon a time all works that arrived at the Gallery were hung. In the last decade, with more than 330 works seeking inclusion this year alone, a selection process has been put in place. Getting 'into' the Award has become increasingly difficult and decisions about who makes the hang are contentious. But, more of that later.

In effect there are two tiers of judging, both critical to the final outcome. The first phase, deciding what will be accepted and hung, is undertaken by a selection panel of five: two MAGNT staff including the curator of Indigenous art, and three external participants, at least two of whom are Indigenous. The panel meets for around two and a half days to view a PowerPoint presentation of submissions. Each year at least two of the external panellists are changed and this, according to MAGNT Director Anna Malgorzewicz, is a key strength because the aesthetic of the selection panel is not predictable.

By all accounts the cull is arduous and one member described it as 'heartbreaking' and increasingly difficult each year. Panellists individually respond to the images with a 'yes', 'no' or 'maybe' and then go through each image as a group aiming for consensus. Many 'nos' are relatively straightforward, often on the grounds of the work being unoriginal or derivative. Presentations on behalf of particular artworks can get extremely passionate as can be the defence of others. The four to five 'sifts' this year required an additional final day of consideration. Gary Lee, a participant in the selection panel for eight years, (also a Larrakia artist and assistant curator for Indigenous Art) said 'Each year an increasingly higher standard of work is being culled. Sometimes the only criterion for rejecting a work is: not enough room.' What are we to make of the information that a number of the 2004 prize-winners were on the 'maybe' list for inclusion in the hang?

All Museum staff involved in the Awards and selection process bemoaned the lack of Gallery space for the Awards. Current wall space is approximately 450 square metres but an ideal would be 1000. Over the years there has been a move towards monumental works and the decision to include a very large painting automatically means three or four smaller works are rejected. Three very large Papunya Tula paintings occupy a huge wall, two of which are the least interesting (can I say least exciting) paintings in the hang. A suggestion has been made that all works not included in the final exhibition could be included in a website – a virtual salon de refuseés. The sheer quantity mean a physical hang in an alternate space would be out of the question. The website concept has a lot of merit but would obviously require funds and a will to create, perhaps next year? Then we could see 'the fabulous works that didn't make the show' according to Margie West (Curator Indigenous Art, MAGNT and founder of the NATSIAA).

The second phase of judging is the formal process: two judges are brought together – one Indigenous and one non-Indigenous – to select the Award winners in the week before presentation. Judges are allocated two whole days to work through the exhibition and gather their thoughts. Apparently this year there was a high degree of congruence between Dr Julie Gough (Curator of Indigenous Art, NGV) and Edmund Capon (Director, AGNSW) and their Judges Comments available to visitors are well worth reading.

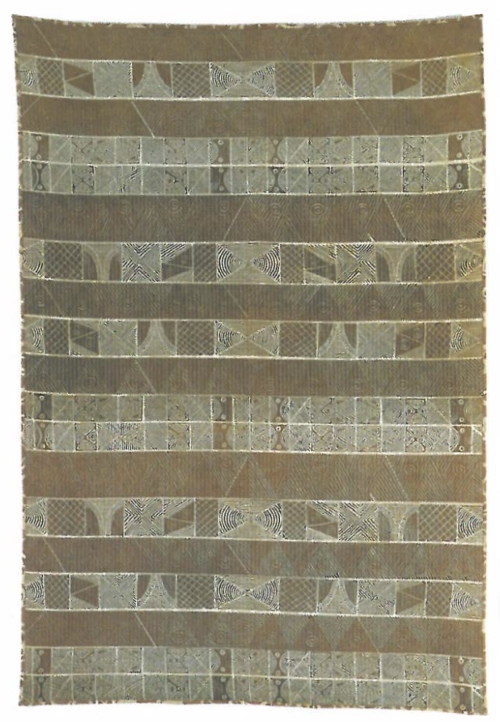

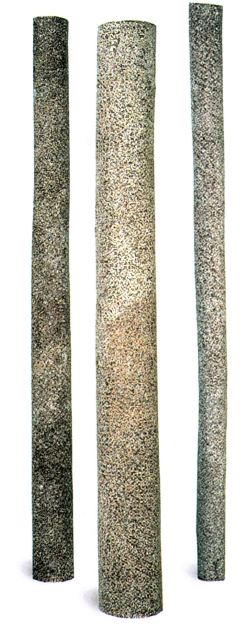

The third act is the media arriving from around Australia on the day before the Award ceremony with the brief to remember to prefix NATSIAA with the name of the sponsor that so generously made our attendance possible. We were given access to those prize winning artists who could be summoned at short notice. The first prize winner, Gulumbu Yunupingu, who had travelled from Yirrkala where she works through Buku-Larrnggay Mulka art centre, sat patiently and with quiet dignity as she was continuously interviewed by various print, radio and television journalists. She expressed her satisfaction at the recognition she was finally receiving as an artist and talked of her next project: to establish a healing centre in North East Arnhem Land. She had known that she had won because 'I felt it in my heart'. She was photographed with her entry Garak, The Universe, an installation of three sublime hollow poles that are an expression of global and universal connection and harmony.

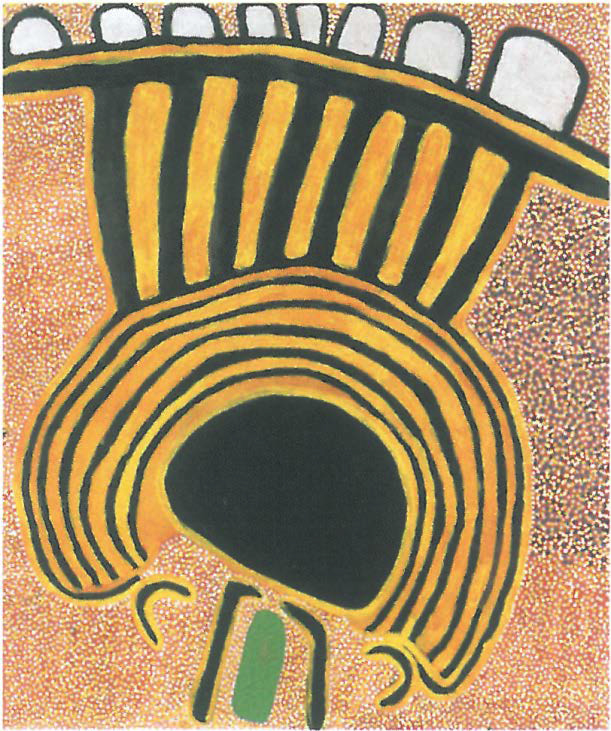

The next day as Gulumbu graciously gave more interviews, Spider Snell, a diminutive former stockman from the Fitzroy Crossing region, sat under the glare of camera lights explaining the significance of his painting (winner of the General Painting category), his country, the permanent Kurtal Jila rockhole he had depicted. He later expanded upon this theme in English and language at the presentation ceremony. It was lovely to share in the beauty of the prizewinners' reactions; their pride, their pleasure at being given the opportunity to explain the meaning of their artworks.

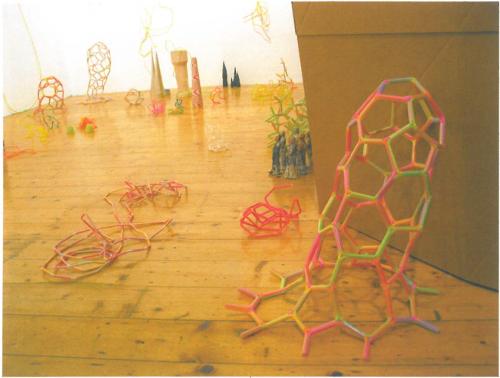

There are many beautiful and humbling artworks in the exhibition, some of the bark paintings are especially strong. A prominent art coordinator was discussing a particular work with Howard Morphy pondering whether it was 'possibly the best bark painting ever'. It was not a prizewinner. The 3D works were amongst my favourites including: a superb possum skin cloak from Victoria, Elizabeth Djuttarra's Yam Sculpture (Ramingining), Nyukana Daisy Baker's large terracotta jar (Ernabella) and Johnny Young's Aboriginal Band at Titjikala. Julie Dowling's incredibly sad painting 'All White Now' was another highlight.

The noticeable gaps this year were Tasmania and the Torres Strait, apparently for want of suitable entries. Artists based in urban areas were well represented, certainly compared to Central Australian communities. A number of key desert art centres were noticeably under-represented or absent (Warlukurlangu Artists, Hermannsburg Potters, Ikuntji), either due to rejection at the first selection phase or because art centre staff or artists had decided not to enter this year due to disappointment following the selection panel rejection of artworks in previous years. Such is the significance and profile of NATSIAA that many artists in remote communities work for considerable time on their 'Art Award' painting and to be knocked back is extremely discouraging and humiliating - particularly for senior artists. That is the inherent tension of awarding prizes, complicated by the growing numbers of contributors. But what are we to make of prizes for Indigenous art? How do we justify saying one painting is better than another when for many Indigenous people a 'good' work is judged by criteria completely unrelated to aesthetics.? An artwork's merit is in its veracity, its faithfulness to a place, a Jukurrpa, a Djang, a creation story, and is evidence of the artists' rights and responsibilities to 'paint it proper way'.

Choosing to submit a work to the Award means making it unavailable for sale for at least three months before it is known whether it will be selected. All works submitted must be available for sale and the artist must wait until the opening before it can be purchased.

Growing from a small and very homespun affair in the 1983, the NATSIAA Award is now slick, prestigious and corporate sponsored. There were no less than three different 'events' in the final act: the Preview for journalists and special people (Thursday evening), the Artists' Preview (Friday afternoon) and the opening itself (Friday evening). The Awards are now too huge to schedule all events at once as not everyone fits in the Gallery and access has been a problem in previous years.

Were there trends this year compared to previous years? The most distinctive trend had little to do with art and everything to do with commerce - with prices heading skywards. Significant numbers of works are large and approximately 20% were entered by commercial galleries. Technically all works hung are available for sale, however some will be acquired by MAGNT and others have already been spoken for by institutions and collectors.

With many artworks in 'The Telstra' on the walls for more than $10,000 and some as much as $40,000 institutions are finding it extremely difficult to compete with the collectors. Just being hung in NATSIAA has cachet and builds value in individual artworks and the reputations. It seems a shame that MAGNT, an institution run on a very modest budget, is not able to capitalise on the prestige it has generated. The unwillingness to charge a commission on sales now is primarily due to discomfort about a perceived conflict of interest around the charter of cultural institutions. This is highly debatable.

MAGNT appears to be giving the gift of exposure and prestige to the artists who make the final hang with flow-on benefits to their art centres and dealers. Art centres are selling their artworks through NATSIAA at inflated retail prices (let's be honest about the way artworks are priced for the Award) and could easily accommodate a commission of 20 – 30% going to MAGNT. And MAGNT could negotiate to earmark income generated through the Award to acquiring artworks from new and emerging Indigenous artists. As it stands commercial dealers who successfully enter artists from their stable are getting a free venue for three months, maximum exposure, and even the opportunity to be included in a touring exhibition, in addition to a handsome sale price.

Like many things that grow from humble beginnings and gain unanticipated momentum the NATSIAA is now facing challenges that are consequences of its success. The advent of corporate support and subsequent increase in prize money has brought greater prestige, as has Telstra's willingness to budget for journalists to attend the awards and garner increased publicity for the Awards and their sponsor. The stakes for artists, art centres and dealers are higher – those who miss out have more to lose.

However, all these issues seemed so far away as we sat in the night watching the stage where body-painted, red-skirted Tiwi ladies and Tiwi men dancing the crocodile and turtle stories moved towards each of the Prize winners, as the singer's voice rang out over the warm night air, as the winners graciously took their prizes and stood at the podium to say thank you - everyone was proud.