The heat-wave of Brisbane's summer months, together with the endless days of school holidays, invariably propel hordes of less than regular visitors towards the air-conditioned interior of the Queensland Art Gallery.

This summer the star attraction for kids is the Lost and Found exhibition, with posters advertising its trademark Arty the garden gnome peeping out from hoardings and bus shelters right across the city. The exhibition is the eighth in an ongoing series that focus on interpreting art to children, (all fabulously successful in terms of drawing crowds), launched as part of a new museology initiative. They are as far from being intended as a means for providing play activity in the gallery as they could be, instead aiming to provide a means through which children – and other age groups – can engage meaningfully and productively with contemporary art.

The way in which QAG has developed such shows has become increasingly sophisticated as confidence in, and public response to their initiative has steadily strengthened. For the first of these exhibitions curators would commit themselves to searching the QAG permanent collection for more unusual – perhaps oddball or quirky examples of work – to give the show a special appeal. More recent exhibitions, on the other hand, have steadily included work of more central concern. The brief for the present exhibition was to include some of the most dynamic, challenging and inventive works – works that might be included in cutting edge survey shows of contemporary art - and to draw them together around the theme of Lost and Found. The result is an exhibition that refuses to be sidelined as a children's activity centre by the sheer dynamics and intelligence of the work included.

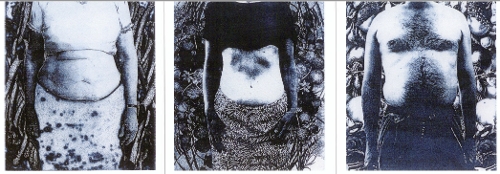

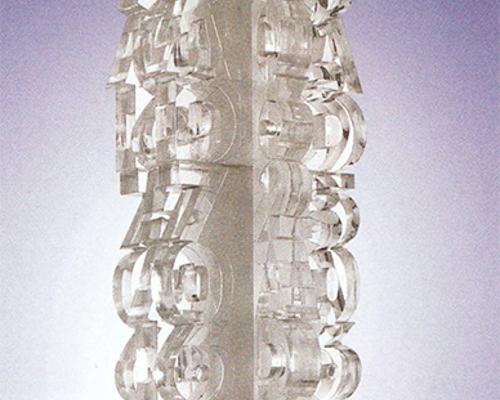

Installations such as that of Indonesian based Mella Jaarsma's animal skin shrouds are sensually captivating as well as politically and imaginatively challenging. Here skins of fish, chicken and marsupials are stitched together into cloaks that, to most children, are as evocative of magician's robes as they are of Islamic burkha.

On the other side of the gallery Michael Tuffery's corned beef-can bulls bear the scars of their engagement as ritual objects, and suggest the possibilities of everyday objects being transformed into works of incredible strength and endurance. A video documenting Tuffery's performance using the bulls in a ritualised battle during one of the APT's opening events adds to the sculpture's intrigue. Here is an art work made from the detritus of an everyday consumable; yet it has been transformed by the artists' hands, the community's engagement, plus a little smoke and fireworks, into an object marking an ongoing series of rituals associated with the Gallery's history. The kids see the scorch marks and the scratches and want more information. It helps if you were there to explain the details. And if you weren't, there are the didactics, the video, and the extensive written material beyond the exhibition itself.

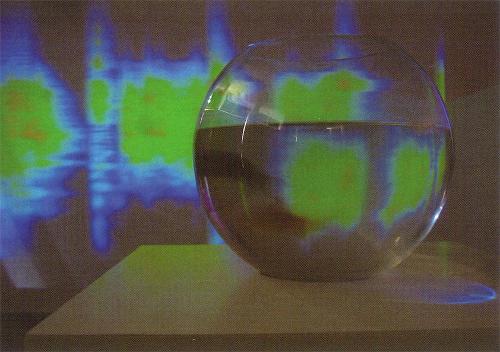

The home-made quality of Austrian artist Erwin Wurm's sequence of videos (1994-2000) heightens the fascination of the simplicity with which simple objects can be seen to perform impossible tasks. Here we see teapots pour their contents into cups from below, or the flame of a candle shoot off sideways, or objects balance precariously, impossibly, as they defy gravity while magnetising fascination. How could this be so? In this exhibition the objects seem to enjoy their liberation from the rational world as much as the audience does.

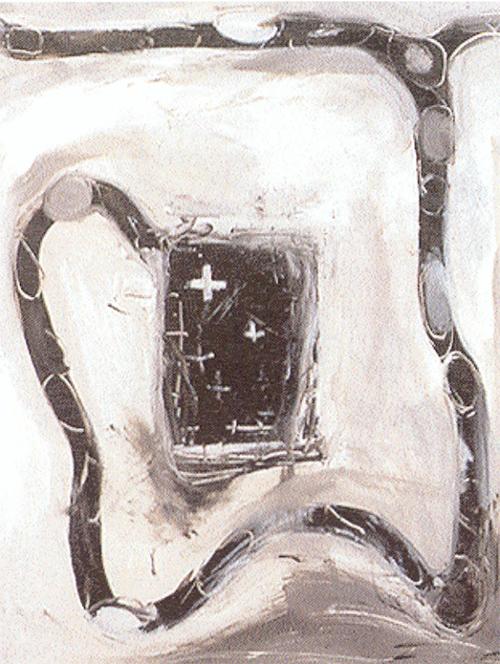

In these works, as with many of those displayed as part of the exhibition, the viewer is left with a sense that there has been a kind of simple magic engaged in. Jaarsma's skins could be those of a shaman, and Tuffery's role as the director of a contemporary mock-battle where both participants and art become entwined in the rhythms of engagement suggest the role of artist as transformer of the everyday. With this in mind, the invention of Arty the garden gnome as a denizen of the realm of magic was crucial to the intention of the project. In this exhibition the mysteriousness and transformative power of art never seems to be too far away from the seriousness of fun.

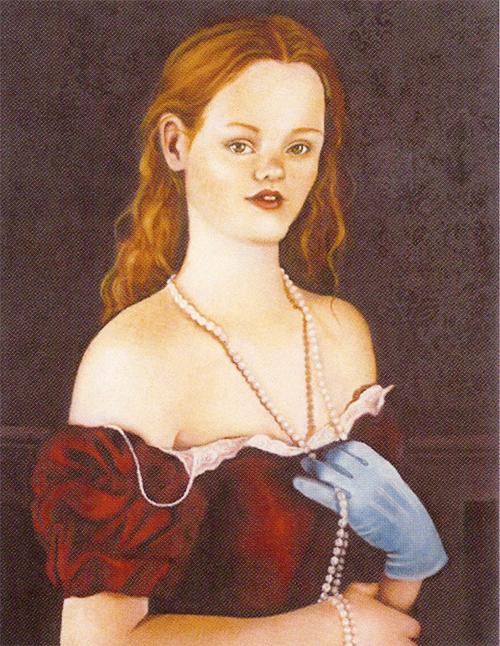

Central to the exhibition's layout is the Arty's Studio activity centre, where children are offered the opportunity to respond to some of the ideas and artworks included in the exhibition. The materials offered to the children don't fall into the buckets and bottle-tops of typical pre-school busy-time. Rather, they were assembled with the beauty of simplicity in mind, and offer a very narrow and evocative range of materials assembled with the advice of Brisbane-based artist Madonna Staunton, whose work is included in the show.

With the exhibitions to date drawing capacity crowds, the QAG staff sees the excitement and involvement of the children, their carers and parents, as a challenge for the future. In the words of Lynne Seear, Assistant Director of the QAG, 'The task for us is to hold onto them'.