The biennial Melbourne Art Fair is the moment when the most powerful art dealers in Australia and the region come together to test the market for their precious commodities. The air is thick with class and privilege as one wanders the booths with their perfect white walls and immaculate furniture. The marvellous contradiction of art fairs lies in the contrast between this most gorgeous of trading floors and the suppliers of the goods on show.

So it may be a good moment to talk about resale royalties in Australia, something which is currently being considered by the federal government.

As the name suggests these are royalties paid to artists or their heirs each time the work is traded. The average figure internationally forth is royalty is around 5% of the selling price and typically the right exists for the lifetime of the artist plus 50 or 70 years.

The debate on resale royalties has been going on in Australia on and off for the last 20 years, with many attempts by the National Association for the Visual Arts and others to persuade the sector and the government to embrace it and so to fall in line with the majority of developed nations. So far to no avail.

However, the major enquiry into the visual arts and craft delivered in 2003 (the Myer Report) included recommendations on more than just increases in funding. It urged a range of fiscal and legislative changes be actively pursued, including the introduction of a system of resale royalties. And so, the Department of Communications, IT and the Arts (DCITA) this winter issued a well-researched discussion paper and invited submissions from the field. The options now are for government to introduce legislation to enshrine the principle and help set up the mechanism, to opt for some compromise arrangement, or heaven forbid, to shelve the whole thing yet again.

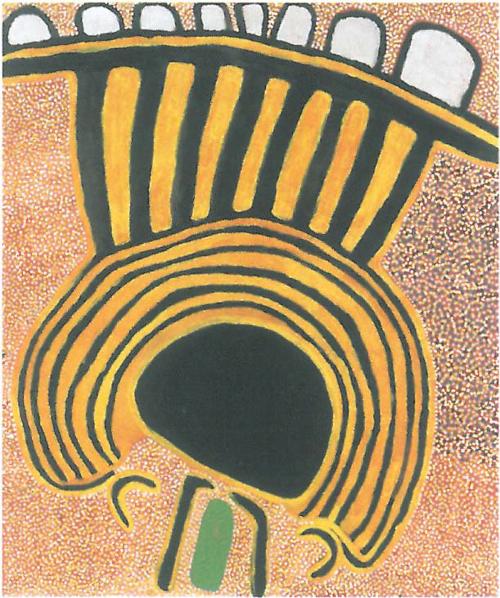

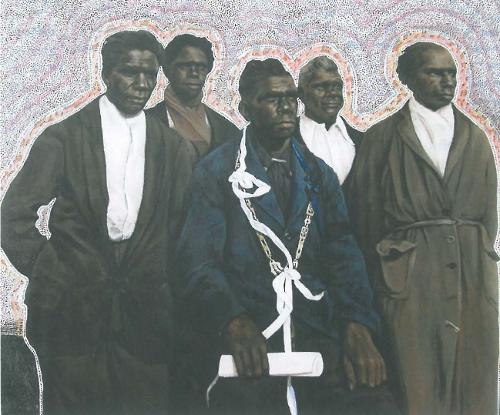

The secondary market for the work of Australian artists is growing exponentially with very high prices fetched at auction, prices which have somehow climbed into the bracket once occupied by old masters . By contrast the first time a work by a living artist is sold it is usually for a small fraction of subsequent transactions. A 1991 painting by the late Rover Thomas, the celebrated indigenous painter from the Kimberley, which he more than likely sold at the time for a song, fetched almost $800,000 only ten years later at a Sotheby's auction. As far as we know not a cent went back to Rover's estate.

In a capitalistic world the notion of profit-sharing on the sale of an asset is a contradiction in terms. After all, when a house is sold who thinks of sending a share of the profit to the person who built it, or their heirs? This seems to be the bottom line for those who are opposed to paying royalties. But in the thrill of the chase some dealers may have forgotten the nature of the business they are in.

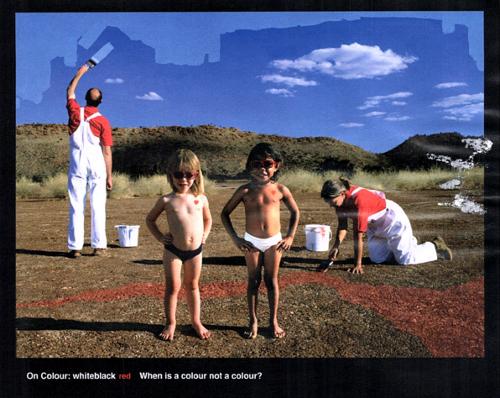

This is where the grand spectacle of an art fair becomes a metaphor for the complex nature of the issue. Despite appearances to the contrary, there is a lot more going on here than just turning a quid and it obviously relates to nature of the goods on sale and their origins far away from the bright lights of the Royal Exhibition buildings. Their source is the minds and the imaginations of a bunch of dreamers who are on the whole so poorly regarded by our society that most have to work at other jobs to allow their dreams time to materialise. The prevailing ethos in Australia now allows for the acceptance of things which only a decade or two ago would have been unthinkable (the treatment of refugees, politicians who lie and smile, a regime under which Australia has become, with the USA, a global ethical pariah in refusing to sign international protocols on human rights and the environment). This is a symptom of a profound and widespread loss of imagination and the ability to visualise the way things could be better.

Visualisation of new paradigms is one of the roles of artists and intellectuals and the art which is seen at the Melbourne Art Fair is part of the larger whole of a culture of conscience, in which things can and should be different.

Knowing that artists are not th e suppliers of common commodities but an essential part of a healthy and thinking society means that we neglect them at our peril.

Given th at they are currently at the bottom of the food chain in terms of earning a livelih ood from their work, anything that can be done to create an income stream, however small, and however remote, should be put in place.

For example the declaration of Viscopy as a collecting society has meant that all artists including emerging artists who join Viscopy and whose works are reproduced in Artlink or other magazines, will receive a cheque in the mail. It may be small but if you are on the dole it could mean the difference between making the next work or not. Australia is far behind many countries in this thinking. There are nations where artists are exempt from tax, who get living allowances, who receive a whole range of benefits, including resale royalties, to enable them to continue to practise.

The argument that the only artists who receive resale royalties are either dead or those who are already very well- off, breaks down under this analysis. Many of the estates of famous artists are themselves charitable entities who help younger or strug gling artists, and many blue-chip artists during their lifetimes are not averse to recycling money back into the art community.

To explore oth er aspects of the debate the DCITA paper can be read at www.dcita.gov.au - click on 'consultation' and the NAVA submission is at www.visualarts.net.au. Readers are encouraged to lobby their local member to support legislation for resale royalties. We are closer to success in this than we have been for twenty years.

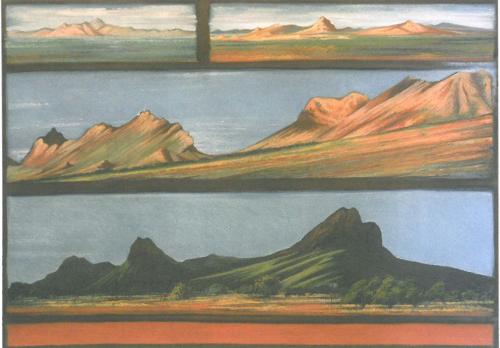

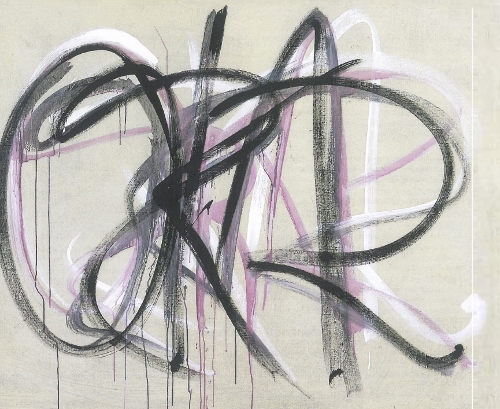

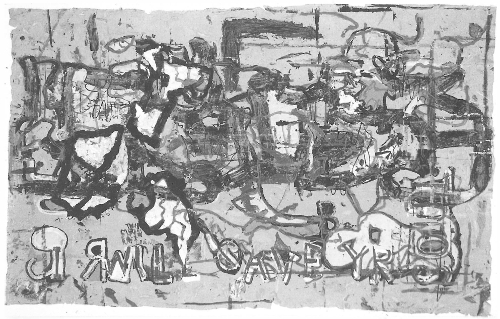

The rich and imaginative work of the eight artists featured in this issue, Michael Jagamara Nelson, Gosia Wlodarczak, Catherine Woo, Gunter Christmann, David Wadelton, Narelle Autio, Paul Hoban and Sue Ford are all candidates for resale royalties.

Their dreams for our world are explored in the following pages.