It is not easy to get a fix on the reasons for the rapid success of Chinese contemporary art. Rarely does one attend an international visual art event in which Chinese artists are not participating. It is equally rare that the art presented by those artists is not also amongst the most challenging of the art on offer.

The question must be how do we approach an understanding of where this art is coming from and how such a new player on the world stage became so important so quickly.

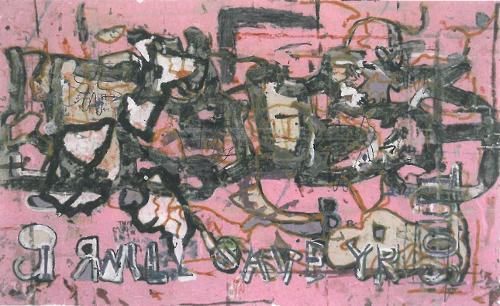

It is significant that one of the first groups to take advantage of the Chinese 'Open Door' policies was a group of artists wanting to express modernist ideas. The group calling themselves 'Stars' put on an exhibition of modern art within twelve months of the end of the Cultural Revolution. Needless to say the Chinese authorities quickly closed it down. What is most significant is how a loose collection of young individuals was able to produce what was an exhibition of modernist understanding when at the time they officially had no experience of modernism.

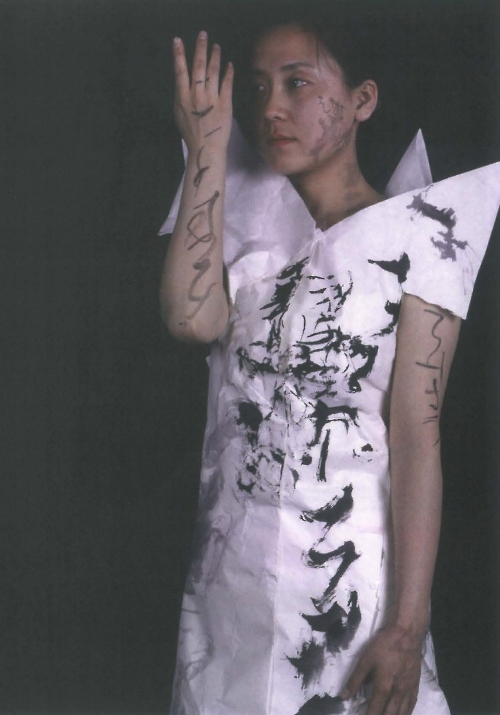

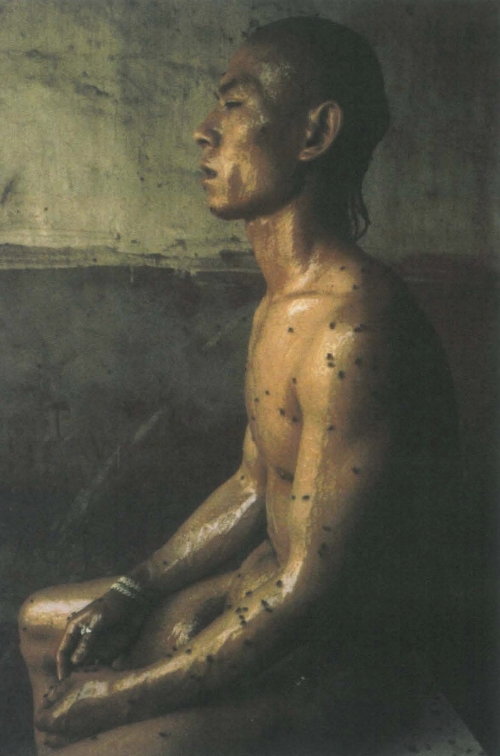

Visual art in China is culturally important. Along with poetry and political criticism it is seen as an expression of new thinking. This is what makes it so dangerous. Consequently it is not unusual that creative individuals will put so much effort into exploring, redefining and honing their expression. By the same token it is not unusual in China that the government may find their activities confronting.

Chinese contemporary art went through an intense incubation period in the late seventies and during the eighties. The external factors at play are almost as important as the determination of the artists to make up ground and truly see themselves as part of a contemporary world. The western fascination with the exotic, forbidden, secret state of post Cultural Revolution China supplied the initial impetus for development. Chinese artists quickly took every advantage of this artificial foreign interest to assume what they believe is their role in leading cultural change and debate in China.

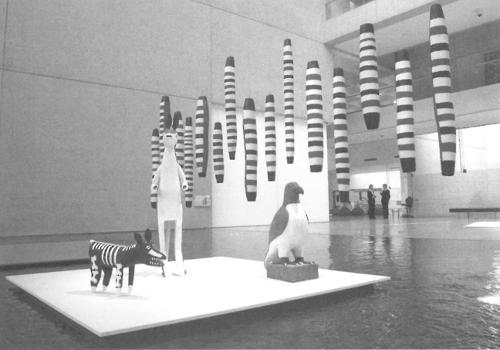

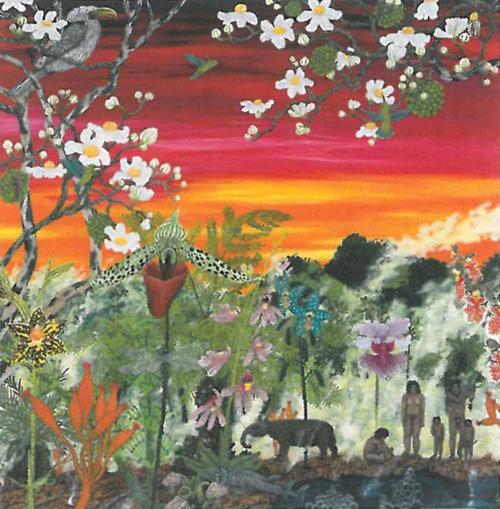

The success of Chinese contemporary art outside of China is in many ways a bonus financially and more importantly it symbolises the Chinese entry into a world community. There is however no single explanation for Chinese contemporary art. In such a populous nation artistic expression has complex themes and is expressed in a multitude of ways.

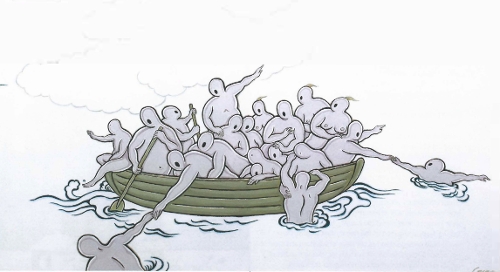

We are living in a globalised world and few of us are able to fully understand the implications of this. Maybe the isolation of the Cultural Revolution and the desire to be set free in the world has caused Chinese artists to embrace contemporary culture in a way which is different from that of artists arriving via an evolutionary path.

This issue of Artlink entitled The China Phenomenon attempts to understand how and why Chinese artists have become so important to contemporary art in a period of less than 20 years. There is no definitive formula. The process is a complex combination of timing, culture, acceptance, drive and passion. Whatever attitude the art world takes, clearly Chinese artists have arrived and they have done so in spectacular fashion.

Most of the writing in this issue looks not at history but at Chinese contemporary art today. The authors, drawn from China, the USA, Hong Kong and Australia, talk of the resourcefulness of the emerging generation of young Chinese artists, some of whom take experimentation to extreme levels; of art of outstanding social responsibility alongside things Westerners find shocking; of returning artists who are able to source assistants to make ambitious highly crafted works; the indication that even performance art, still frowned upon, may soon become officially sanctioned.

What they share is a determination to abandon issues of the exotic in favour of an exploration of one of the most overwhelming forces acting upon contemporary art in the world.

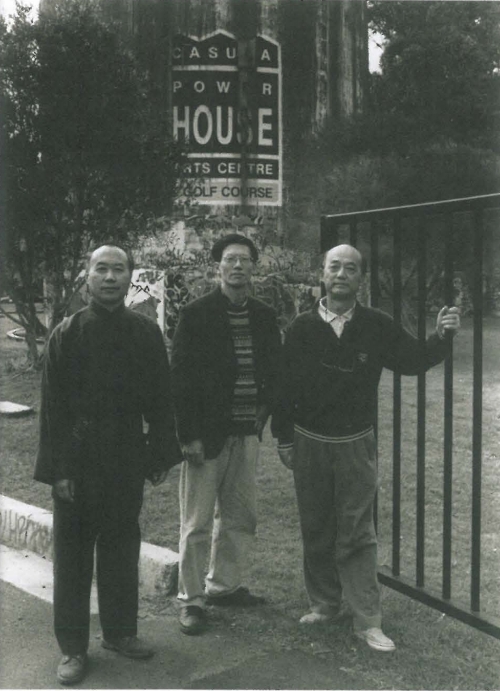

Binghui Huangfu & Stephanie Britton, co-editors.

POSTSCRIPT

In Australia we have developed considerable expertise and scholarship in relation to modern Chinese art and there are many private enthusiasts, but leadership from official circles at the moment is conspicuously lacking. Brisbane's Asia-Pacific Triennials, initiated in 1993, paved the way for public understanding of the contemporary arts of Asia, and the catalogues of those events are precious study resources. Currently there are people working to bring Australian audiences face to face with Chinese contemporary art practice on a more regular basis. In this, as in so many things requiring vision, the government is not providing appropriate levels of support. There are very few opportunities for the nurturing of what is certain to be a significant force in the shaping of contemporary Australian arts and culture.

We hope you enjoy the fruits of what has been for Artlink a most stimulating research project with co-editor Binghui Huangfu, new Director of the Asia-Australia Art Centre in Sydney. Thanks to the assistance of the Australia-China Council, we will take copies of this issue to Hong Kong, Beijing and Shanghai in March 2004. Thanks are also due to the NSW Ministry for the Arts for their assistance to this special issue.

Executive Editor Stephanie Britton