Let me set a scene: Hanoi Fine Arts College, the leading visual arts institution in Vietnam; a hot September morning in 1992 in a plain room with cracked plaster walls and a low table with tea and whisky on offer; a row of smiling middle-aged Vietnamese art school academics, all men, with a young translator. And me.

I had two days in Hanoi, after being in Manila, to try to explain what the first Asia Pacific Triennial was about, and then to try to see as much artwork as possible from which to make recommendations for this new unknown venture in Australia, which was only an idea in people's minds in Brisbane at the time.

Letters had previously been written to the school to try to set up a co-curatorial advisor, as had happened in the Philippines, but there had been no reply. (Language is one issue, and the concept obviously another.) I had tried to find out beforehand what was going on in Vietnamese art but published material, especially with reproductions, was extremely limited: there had been a book published in Hong Kong, an article in Time magazine, old books and magazines bought on a trip there in 1990, and conversations with the very few other 'art' people in Australia who had visited. One helpful contact was artist Katy Munson who lent material she had collected on her visit. From this I wrote up a very preliminary list with five names.

Before this trip, I had had to argue for the inclusion of 'Vietnam' in this first APT to the National Advisory Committee. I was the only one on that committee who had visited there and knew there was an art scene of some vigor, and it also seemed important because of Australia's recently vivid relationship with the country, and its resultant refugees. So a trip of two days was agreed (only to Hanoi) and 'one artist' - fine.[1]

The Art Institute in Hanoi, it turned out, had received my letter, but misinterpreting it, had already decided on the particular artist they thought should be chosen - an artist who worked very beautifully in watercolour on silk and was a senior member of the College staff. We visited his studio. He had an exhibition on nearby which we also visited. But I wanted to see more than this. I wanted to work with the Vietnamese as a partner, not just be told, but I didn't want to tell them either. Impasse. What was to be done? How was the role of the curator to be explained? It was one of those terribly difficult moments of cultural misunderstanding that remains vivid in one's mind. The only way out was to bring out the scrap of paper with the five names and ask to see their work too. Consternation. But quickly the head of the Artists Association was called. She arrived, saw the list, and equally quickly a meeting was arranged with as many of the people on that list as possible. Four people came, with tiny photographs of their paintings. There wasn't time to see the works in reality. The final recommendation to the QAG hierarchy was made from those four people's little photographs - with a slight sway towards Nguyen Xuan Tiep through Katy Munson's comments that she admired his work - she after all had seen it in reality.

And Mr Tiep's works came to Brisbane - the first time a Vietnamese artist had been invited to an international art exhibition I believe. And he came - supported by the Vietnamese Ministry of Culture. That was great, and totally surprising. And the Gallery bought one of his works.

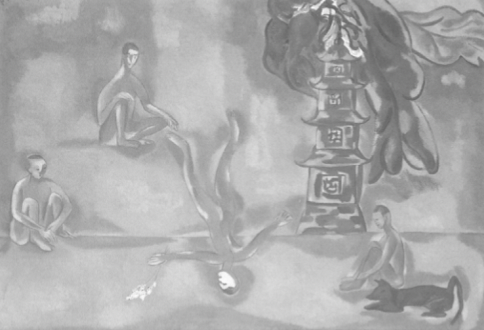

The Vietnamese selection was criticised at the conference. Only one artist, they said, wasn't enough. What could I say? And people didn't like his particular work. I could only defend it - that I was responding (to the actual experience in Hanoi and) to the belief that has always driven me through three APTs: that all curators must not only be thinking of the audience in Australia but also the interests of the place where the works come from. And Vietnamese artists certainly at that time were only working in the romantic elegiac paintings such as those made by Mr Tiep. They passionately believed in that mode. The alternative - State-led, politically-driven work which, ironically, would have been much better received in Australia - was at that time of doi moi an anathema to every artist. They said "we are free now; we only paint what we want" and they wanted to paint elegies to the old ways.

Having said that, Mr Tiep's work was out of step with the rest at APT. A different focus totally. And still Vietnam remains 'out of step'. Selections in the next two triennials have also remained remarkable by their refusal to conform to an APT dynamic. It's partly of course the political situation. Vietnamese have fought hard for their national sovereignty. They wish to hold on to that and the symbols of Vietnamese life. It's a conservative society, Confucianism mixed with Communism, especially in the north. And it's partly other things intertwined with this - lack of information certainly about what is going on elsewhere, and people in entrenched positions who don't want to know. This is important. Additionally, with doi moi and the increase of foreigners going to Vietnam, often with personal emotional baggage, pictures of this ideal Vietnamese life started to sell very well. On salaries of $10 per month, selling paintings for over $1,000 is very persuasive.[2]

This is one story. There are hundreds of others in the development of the APT. Particular circumstances, contacts or the lack of them, incidental meetings, and local pressures have all had an important part in the development of this ten year project. And this has been one of its great strengths. So many people have been involved, all bringing their own enthusiasms to it and learning to cross various hurdles along the way. And so many of the selections, of course, come from this totally human, relatively idiosyncratic, and somewhat anarchic reality.

It is continually surprising that people see plots and strategies for a project like APT. On one level we can only laugh and say "if only".

Footnotes

- ^ One of the remembered criticisms of the third APT heard resounding from a number of people is that Vietnam this time needed "four curators to select three artists". It is only good this was so. The number of artists has gone up so that one person does not bear this lonely mantle. And four curators: one young Australian learning; one experienced Vietnamese-wise Australian; one curator in Hanoi; one in Ho Chi Minh City. Anyone with any knowledge of Vietnam realises the realities and appropriateness of this.

- ^ The alternative situation of Chinese artists hasn't occurred in the same way, partly because they didn't have this emotional and then economic imperative.