Shared experiences, of colonialism, of migrations, the attendant changes that these histories bring and, most significantly, the importance placed on the local that looking at geography delivers are some of the special contributions of Brisbane's Asia-Pacific Triennial.

Jostling within this domain are tensions that are inevitable and essential amongst which is an awareness that geography can be considered as arbitrary as any other selection criterion.

For instance, there are artists who elect to make work for the APT that "...isolate exotic national characteristics legible to disinterested, even uninterested, observers, and manipulate them within an internationally acceptable syntax."[1]

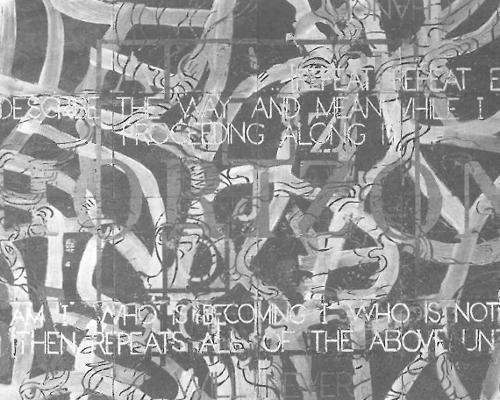

In this sense the APT can be seen as teasing out critical positions in regard to location (global or local or both). At other times it seems to demonstrate a seeking of humour borne of necessity; it also explores the articulation of difference in the forms of changing identities. The work of Mella Jaarsma, Simryn Gill and Tim Johnson spring to mind in this regard.

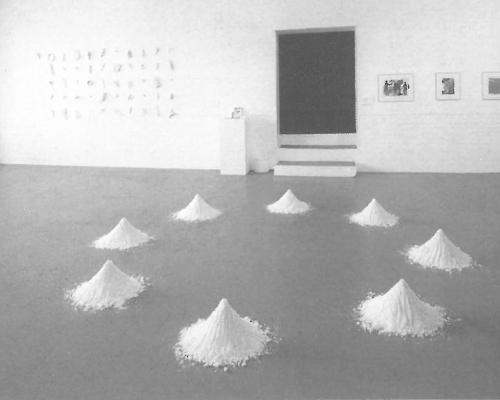

Hi inlander (1999), an installation by Dutch-born Indonesian artist Mella Jaarsma that incorporates performance, uses the treated skins of frogs, chicken's feet, dried fish and kangaroo hide to form jilbabs (the veils worn by Muslim women) which were hung inside the Gallery. During the festive opening nights of the Triennial, Jaarsma and others cooked these four meats for guests to eat. In its first context Jaarsma's work used quite specific emblematic ingredients related to Indonesia (eg. the frog's legs and chicken's feet are Chinese delicacies considered unclean by Muslim Javanese) in what became a literal enactment of and comment on cultural ingestion. Yet in Brisbane this barbecue style cook-up was inflected with a peculiarly Australian resonance ( multiculturalism is most often celebrated here as a festival of food) ensuring an irony not lost to this work but instead serving to heighten its power.

Tim Johnson is an artist who has worked consistently with others over his career. In Johnson's installation After Mt.Meru (1999), Tibetan artist Karma Phuntsok, Vietnamese My Le Thi and Australian Edward Johnson all worked with Johnson to construct a set of images that draw on particular local traditions to realise the final works. Johnson is also known for his collaboration with Western Desert artists including Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri and Michael Nelson Jagamarra. This commitment to a collaborative practice that is aware of the difficulties of negotiating questions of appropriation, acknowledges a local spirit, a particular dynamism in which cultural expression registers, real or otherwise, the potential for a multiplicity of narrative viewpoints.

Another of the APT's contributions is that it recognises that we belong to a world that is increasingly complex and fluid, a world in which what is 'East' or 'West' are porous and offer possibilities of claiming different and numerous cultural identities. The inclusion of expatriate artists who attest to the fluidity of cultural practice and thereby test the notion of recognisable nation-state visual practice, introduced an important element to the third APT. The notion that artists represented countries became a kind of tautology, admittedly more for some than for others.

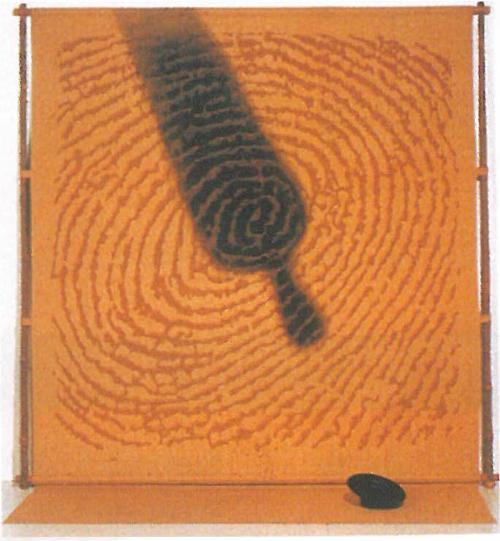

This inevitably introduces the issue of indigeneity, because of its relationship to notions of identity. Although traditionally associated with the Pacific contributions, due to their close relationship to an extremely local community-based performative art practice, the issue of indigeneity had a much wider and more nuanced expression in the third APT. Seen in the Australian selection of artists such as Tim Johnson and Guan Wei, or other artists such as Sonabai from India, John Frank Sabado from the Philippines and Mella Jaarsma from Indonesia, it is Simryn Gill's work Vegetation 1999 that directly attempts to unravel this issue in all its messy reality.

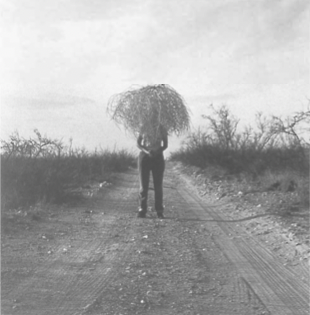

Vegetation consists of five images, two set in Texas, USA, two in Australia and one in Singapore. Each photograph stars a plant species that Gill has chosen because of its associations with being indigenous to a particular location. The tumbleweed and aloe are from the deserts of Texas, the grasstree(Xanthorrhoea) and mangrove from the Australian bush and the tree-fern from the lush tropical landscape of Singapore. In each image is a single figure, placed in the allocated environment, who sprouts from her head one of these plants. Apart from looking exquisitely funny, the questions that well up around these photographs perform to global and local issues that are in fact very ancient, as long as human beings have lived and moved across the globe. "At which point do I become native to this place?" or "When do my roots take and confirm me to be part of the local?"

Finally, the APT is the only significant recurrent exhibition in Australia that continues to look at the contemporary art of the Asia Pacific. Integral to this project is the building of a collection. Indeed the first APT was catalytic in the formation of a collection of contemporary Asian art for which the Queensland Art Gallery is now well-known. As it stands, just under one third of the Gallery's contemporary Asian collection was acquired from the three APTs of 1993, 1996 and 1999.

The APT involves many artists arriving in Brisbane to install their work in the Gallery. Although a number of these artists participate in residency and teaching programs across Australia as a result of their inclusion in the APT, as an exhibition it is too large to tour. However there is now a regional exhibitions program that ensures the Contemporary Asian Collection travels throughout Queensland.

Much has been made of the APT curatorial structure, which is predicated on a series of curatorial teams rather than a single artistic vision. This has led to charges that the exhibition does not have a coherent authored theme. This structure has also been criticised as being too concerned with aspects of cultural diplomacy at the cost of losing curatorial sharpness. Without doubt there are areas in a project of this scale which make it a challenge to understand as a cohesive whole. The 'how' of a project of this nature will consistently be under scrutiny and justifiably so. For what the APT project signifies in Australia must not be ignored, an Australia that is characterised by a post-Keating, post-Asia-economic-meltdown political climate in which a number of issues which were once considered to be important and on the agenda to be resolved are now being partially dismantled (such as Australia becoming a republic postponed indefinitely, the constant procrastination on Reconciliation, economic rationalism at all costs to name a few.) Given then that this is our local context, the dissonance or multiple resonances that the APT generates here distinguish it as a very necessary intervention.

Footnotes

- ^ Charles Green 'Third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Asian Art' in artext No 68 Feb-April 2000, p85.