As part of the group of Ramingining artists whose work during the 1980s and 1990s placed this central Arnhem Land region firmly on the art map, George Milpurrurru drew his essential inspiration from the land and its sacred narratives. His work, however, though rooted in the aesthetic traditions and ceremonial conventions taught to him by his father, was in both its size and sense of design equally innovative in extending and adding new schematizations from the earlier generation of artists. This sense of adventuring into new territory was epitomised by his extremely large painting of men hunting in their canoes created especially for the 1979 Sydney Biennale.

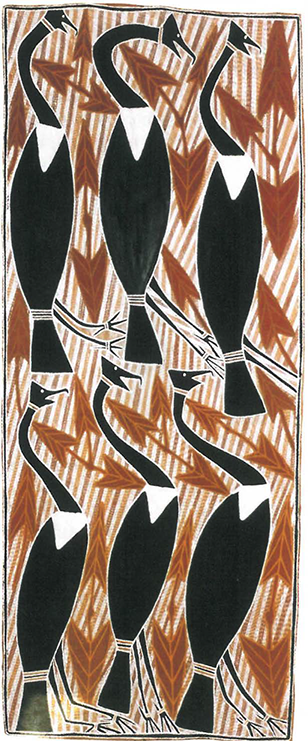

As one of the first Arnhem Land artists to respond to the opportunities of an expanding gallery scene in the 1980s, his solo exhibition in Sydney in 1985 at the Aboriginal Artists Gallery exemplified his capacity to work within both his traditional totemic idiom and extend into a wide-ranging artistic celebration of everyday Arnhem Land scenery and hunting activities. If Milpurrurru's totemic imagery carries on the work and teachings of his father Ngulmarmar, the other side of his output reveals a strong exploratory streak which, for a period included three dimensional additions such as woven fishing traps and birds' nests. His images of collecting magpie geese eggs in the Arafura Swamp and other hunting and food collecting daily life scenes reflect the emotive ties of the swamp to the artist and inspired Milpurrurru to significantly widen the range of subject matter beyond the formal totemic and ceremonial subjects of his other work.

This holistic approach to the range of artistic expression is paralleled by the artist's fierce attachment to his own country of the Arafura Swamp land and his daily life, exemplified by his idiosyncratic but highly successful method of shooting buffalo while perched in a tree, or as a dancer and spear fighter. The consummate focus that Milpurrurru brought to all three activities denotes a single minded sense of balance and of challenge and skill, an attitude equally reflected in his approach to his art.

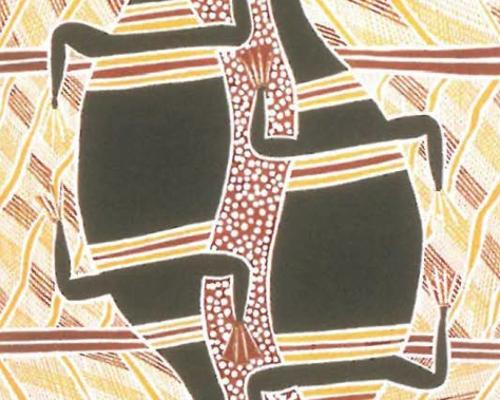

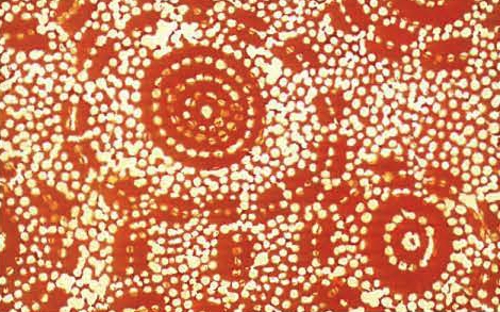

Whether depicting formal totemic imagery such as Warriny - flying fox, Djanyarr - the totemic dog, Karritjarr the rainbow serpent, or more narrative everyday hunting scenes, it is in his approach to design and graphic precision that perhaps most mark out Milpurrurru's artistic individuality. In particular, in his compositions dealing with the above and Mewal - Honey Spirit Dreaming, the artist's approach to spatial organisation carries a strong element of gestalt technique. The play between foregrounded and backgrounded solid areas, enhanced by clever use of the bare bark itself or single colour patterning incorporates a complex shifting of visual focus which in the least figurative of his works can become quite mesmerizing after a period of uninterrupted viewing. If the early public response to his work was partly based on the immediate accessibility of his compositions through its linear precision and 'decorativeness', (especially the floral bat dropping designs) the subtlety embedded within the surface layering and interlayering of surfaces blocks created a much deeper subliminal response.

Beyond the purely narrative reading -'the story' - and identifying the core images, this takes the viewer into a much closer contact with elemental, compositional questions of colour and line and the process of filling an empty space. The crossover between cultural information and an aesthetic where individual style becomes the defining characteristic is perhaps Milpurrurru's most significant contribution to the 1980s in Arnhem Land where major explorations were made among second and third generation artists to redefine the earlier structural parameters passed onto them by their fathers and grandfathers. Extensive travel to attend exhibitions including representation in both the 1979 and 1986 Sydney Biennales enabled the artist to observe and engage with the wider art world especially during the 1980s when Aboriginal projection of cultural and political aspirations were focused through the build-up to the 1988 Bicentennial year. His leading contribution to the 200-pole Aboriginal Memorial permanently housed in the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra reflects his commitment to a wider cultural agenda beyond the confines of his own country and keen sense of the underlying national issues confronting the core question of Land Rights.